Advancing Nursing Education in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Lessons from Bangladesh for Sustainable Global Health

Article information

Abstract

Global disparities in the nursing workforce threaten progress toward sustainable and equitable health systems. This paper presents three initiatives from Bangladesh—including the establishment of the National Institute of Advanced Nursing Education and Research, Chittagong Youngone Nursing College, and Shields Nursing Education Program—to illustrate how coordinated public, private, and international partnerships can strengthen nursing education in low- and middle-income countries. These efforts expanded educational capacity, advanced competency-based curricula, and enhanced faculty development, research, and leadership. Lessons from Bangladesh underscore the importance of embedding nursing within national health strategies, investing in faculty development, strengthening governance systems, integrating digital innovation, fostering responsible partnerships, and elevating the professional recognition of nurses. The Bangladesh case demonstrates that investing in nursing education is a strategic pathway to resilient, self-sustaining health systems and sustainable global health.

INTRODUCTION

The sustainability of global health systems is fundamentally dependent on the availability of a well-trained and adequately staffed health workforce. The World Health Organization (WHO) has emphasized this reality with the assertion that “there is no health without a workforce,” underscoring that the strength of any health system and the achievement of universal health coverage (UHC) rest heavily on human resources for health (Campbell et al., 2013). Despite this recognition, the persistent shortage and inequitable distribution of health care professionals (HCPs) remain among the most pressing challenges in global health.

Nurses represent the largest segment of the global health workforce, yet nursing shortages constitute a particularly chronic and enduring crisis, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). A recent WHO report projects a worsening global nursing deficit, with nearly 70% of the shortfall expected to be concentrated in Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean by 2030 (WHO, 2025a). The magnitude of this disparity is reflected in striking differences in workforce distribution: in 2020, high-income countries (HICs) such as Norway and Switzerland had approximately 165 and 187 nurses and midwives per 10,000 population, respectively, whereas LMICs such as Bangladesh (6.6), Malawi (5.1), and Ethiopia (12.2) fell far below the global average of 37.7 per 10,000 (WHO, 2025b).

This inequity is further exacerbated by the persistent outmigration of nurses from LMICs to HICs, a phenomenon commonly referred to as “brain drain.” Between 2011 and 2021, the proportion of foreign-trained nurses employed across OECD countries nearly doubled, rising from 5% to 9%, with most originating from LMICs (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2023). The United Kingdom alone recruited more than 23,000 foreign-trained nurses between 2021 and 2022, with significant increases from the Philippines, India, Nigeria, Ghana, and Zimbabwe (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2022). Similar reliance on internationally recruited nurses has been observed in the United States, Ireland, New Zealand, Switzerland, Germany, and Canada (OECD, 2023). While such migration alleviates workforce gaps in destination countries, it critically exacerbates shortages in source nations, undermining already fragile health systems. Consequently, LMICs face a dual burden: severe domestic shortages alongside the external pull of global labor markets.

Structural vulnerabilities in LMICs further compound this imbalance. In many of these settings, primary healthcare (PHC) serves as the cornerstone of public health strategy, yet PHC systems remain chronically underfunded and heavily reliant on external aid (Hanson et al., 2022; Oleribe et al., 2019). Nurses—who comprise the backbone of PHC delivery—are both understaffed and under-supported. Weak workforce governance, limited academic infrastructure, and constrained public health budgets have rendered health systems fragile and ill-equipped to respond to both current demands and emerging health threats (Bvumbwe & Mtshali, 2018; WHO, 2025b).

Thus, the global nursing workforce imbalance is not merely a matter of numerical disparity but a structural impediment to achieving equitable and sustainable health outcomes. Addressing this inequity is not optional; it is an urgent imperative for global health.

THE IMPERATIVE OF STRENGTHENING THE NURSING WORKFORCE IN LMICS

Addressing the global nursing shortage—particularly in LMICs—requires more than simply increasing the number of nurses. It demands a strategic shift toward strengthening nursing capacity by developing autonomous, skilled professionals capable of leading, innovating, and responding effectively to complex public health challenges.

In many LMICs, nurses frequently serve as the primary—and sometimes the only—point of contact for patients within healthcare systems. Far beyond auxiliary roles, nurses are essential HCPs whose responsibilities encompass disease prevention, infection control, maternal and child health, chronic disease management, health education, and community-based care. During public health emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses demonstrated their indispensable role at the frontlines by leading triage, vaccination, mental health support, and risk communication efforts (Kang et al., 2024; O’Regan-Hyde et al., 2024). In such contexts, nurses act as critical agents of equitable healthcare access and system resilience (International Council of Nurses, 2021).

Realizing the full potential of the nursing workforce requires robust educational pathways and sustained professional development. Strategies must address both quantity and quality. Rapid scale-up without adequate standards, supervision, and clinical competencies risks producing a workforce that is numerically sufficient but professionally underprepared (Buchan & Catton, 2023). Conversely, highly trained but insufficiently staffed systems face burnout, attrition, and bottlenecks (Buchan et al., 2022). Effective workforce development therefore necessitates a dual commitment: expanding access to nursing education while ensuring that training is competency-based, context-specific, and aligned with national health priorities (Buchan et al., 2022; Buchan & Catton, 2023).

Moreover, locally educated and retained nurses are more likely to remain within their communities, thereby contributing to sustainable health system strengthening. Reliance on foreign-trained nurses not only raises ethical concerns but also fails to provide long-term workforce sustainability (Bourgeault et al., 2023; OECD, 2008). In contrast, investment in homegrown nurse leadership and domestic education systems enhances resilience and mitigates workforce migration pressures (Sharplin et al., 2025).

Sustainable solutions must therefore prioritize the local production and long-term capacity building of nursing professionals within the cultural, clinical, and policy contexts of LMICs. Training should extend beyond clinical competence to include public health, leadership, policy advocacy, and interprofessional collaboration. Such preparation enables nurses to serve as system thinkers and change agents (Clarke, 2023; Maragh, 2011; Stucky et al., 2022). This approach not only strengthens national health systems but also improves population health outcomes, economic resilience, and global health security, while advancing progress toward UHC and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (High-Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth, 2016).

Ultimately, nursing education is not a peripheral operational concern; it is a foundational pillar of health system development. Without a strong nursing workforce, investments in infrastructure, technology, or disease-specific programs risk being undermined by workforce gaps. Investing in nursing education is, therefore, investing in the quality, equity, and sustainability of healthcare systems.

CASE STUDY: EXPERIENCES IN BANGLADESH

Bangladesh, with a population of approximately 160 million, faces persistent disparities in healthcare service delivery due to an acute shortage of HCPs (Nuruzzaman et al., 2022). Compared with the global minimum threshold of 0.5 physicians and 1.5 nurses and midwives per 1,000 population, Bangladesh reports only 0.6 nurses and midwives per 1,000 population, alongside an inverted physician-to-nurse ratio of 0.86:1—far below the OECD average of 8.4 (World Bank, 2025). According to the Bangladesh Nursing and Midwifery Council (BNMC), approximately 71,000 nurses were registered nationwide in 2020. Their distribution, however, is highly uneven: urban areas employed 5.8 nurses per 10,000 population, while rural areas had only 0.8 per 10,000, reflecting a sharp geographic imbalance (Ahmed et al., 2015). Additionally, about 92% of registered nurses hold only a diploma-level qualification, 6% a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (B.Sc.), and only a small fraction holds graduate degrees (Rony, 2021). This skewed educational profile constrains professional capacity and constitutes a major barrier to the provision of high-quality, advanced healthcare services.

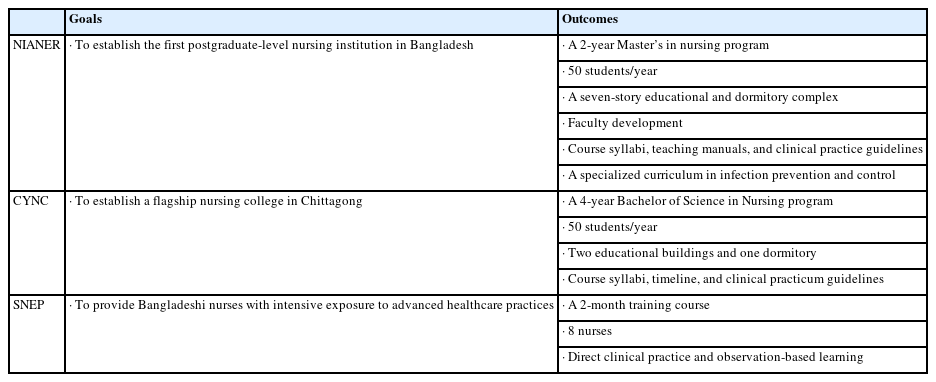

To address these systemic shortages and educational gaps, initiatives were undertaken in both the public and private sectors. First, the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA), Korea’s governmental agency for official development assistance (ODA) that provides grant aid to support sustainable development worldwide, supported the establishment of the Bangladesh National Institute of Advanced Nursing Education and Research (NIANER). During the COVID-19 pandemic, a collaborative curriculum in infection prevention and control was subsequently developed with NIANER. Second, the private-sector partner Youngone Corporation established a four-year Bachelor of Science in Nursing program through the creation of the Chittagong Youngone Nursing College (CYNC). Third, Yonsei University Health System (YUHS) introduced a short-term clinical training initiative, the Shields Nursing Education Program (SNEP), to provide Bangladeshi nurses with exposure to advanced hospital practices.

Collectively, these multi-sectoral initiatives—led by KOICA, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW), the BNMC, Yonsei University, and Youngone Corporation—laid the foundation for sustainable nursing workforce development. The following sections highlight three representative initiatives spearheaded by Yonsei University College of Nursing (YUCN): NIANER, CYNC, and SNEP (Table 1).

The National Institute of Advanced Nursing Education and Research (NIANER)

The establishment of the NIANER originated when Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina officially requested support for nursing workforce development during her visit to Korea in 2010 (Wang, 2018). Following this request, the KOICA launched the project in 2012 with YUCN as a project management consultant (PMC). The initiative was implemented over a seven-year period, with a total budget of USD 13.75 million, and culminated in the formal inauguration of NIANER in Dhaka in 2018 as the first postgraduate-level nursing education institution in Bangladesh (KOICA, 2022).

The project entailed the construction of a seven-story educational and dormitory complex with a total floor area of 9,163.85 square meters, equipped with advanced simulation laboratories, lecture halls, libraries, and other state-of-the-art facilities. More than 600 categories of educational equipment, including simulation-based training devices and electronic systems, were installed to ensure that the training environment met international standards while remaining adapted to local contexts. Alongside infrastructural investments, the project placed a strong emphasis on capacity building. Nursing administrators and policymakers participated in short-term training programs in Korea, nursing faculty members undertook 12-week intensive programs to strengthen their teaching and research skills, and senior government officials attended a leadership training designed to expand the administrative capacity for nursing development. Importantly, Bangladeshi nurse educators pursued doctoral education at YUCN, successfully completing their PhDs and returning to the NIANER as faculty members. As of today, YUCN has supported the training of five doctorally prepared Bangladeshi nursing faculty members who now contribute to NIANER’s academic leadership.

Academic program development was another cornerstone of the project. In 2016, the master’s curriculum designed at NIANER was officially accredited by the Bangladeshi government. The program, structured as a two-year course requiring 48 credits including a thesis, was competency-based and reflected both international standards and domestic healthcare priorities. It incorporated six core competency domains—quality patient care, education and consultation, research capacity, leadership, collaboration and cooperation, and lifelong learning—across six majors: adult nursing, women’s health nursing, child health nursing, psychiatric, community health nursing, and nursing management. The curriculum was re-certified in 2018 to reflect evolving needs in clinical practice and education. By 2019, NIANER had admitted four cohorts, comprising a total of 200 students. Graduates from the program went on to occupy senior nursing positions in hospitals and community health centers, contributing directly to improvements in healthcare delivery and service quality.

Taken together, NIANER represents a landmark achievement in the advancement of Bangladesh’s nursing education system. It not only filled a structural void by offering the country’s first master’s program in nursing but also created a sustainable ecosystem for faculty development, research advancement, and community engagement. By producing highly skilled nurses with leadership and academic competencies, NIANER has become a cornerstone in Bangladesh’s efforts to strengthen its health system through sustainable investment in nursing education.

Building upon the institutional foundation of NIANER, a collaborative initiative was launched by YUCN and NIANER, with support from the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea, to develop a specialized graduate-level curriculum in infection prevention and control (IPC). This initiative emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic, reflecting the urgent need to address Bangladesh’s high vulnerability to infectious disease outbreaks by cultivating advanced practice nurses capable of leading infection control in both clinical and community settings.

The development process was guided by the ADDIE model (Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation). The analysis phase involved a situational assessment of IPC practices in Bangladeshi hospitals, identification of the roles and competencies of practicing nurses, and recognition of the growing demand for infection control nurse specialists. In the design and development stages, a structured 48-credit curriculum was created, integrating theoretical courses, laboratory simulations, and clinical practicums. Five IPC-specific courses were developed: three theory-based (Advanced Infection Prevention and Control Nursing I and II; Clinical Microbiology and Immunology, 9 credits) and two practicums (Advanced IPC Nursing Practicum I and II, 6 credits). The theory courses introduced global IPC standards and extended them to population- and setting-specific contexts, while the practicums emphasized the translation of theoretical knowledge into practice, incorporating best practices across diverse hospital departments, community-based interventions, and policy decision-making relevant to outbreak response in Bangladesh. The elective course Clinical Microbiology and Immunology further strengthened students’ understanding of infectious diseases prevalent in Bangladesh and provided them with competencies to independently investigate and implement prevention strategies. Learning objectives were aligned with international infection control standards while remaining tailored to Bangladesh’s healthcare environment. To ensure quality and sustainability, faculty teaching manuals and clinical practice guidelines were also developed to support consistent program delivery and evaluation.

This curriculum represented the first systematic effort in Bangladesh to train advanced practice nurses in IPC. By equipping nurses with specialized competencies, the program sought to improve individual clinical practice, enhance institutional infection control capacity, and strengthen the resilience of the national health system. Moreover, it established a pipeline for developing nurse leaders who could contribute to national health policy, nursing education, and research in IPC. Importantly, the project was initiated during the COVID-19 pandemic, enabling a timely response to an unprecedented public health crisis. By developing educational models that are both contextually relevant and globally benchmarked, the initiative not only addressed immediate clinical needs during the pandemic but also reinforced Bangladesh’s preparedness and long-term capacity to respond to future infectious disease outbreaks.

Chittagong Youngone Nursing College (CYNC)

The CYNC was established in Bangladesh’s second largest city, Chittagong, as part of a broader initiative to expand high-quality nursing education beyond the capital. The project was initiated by Youngone Corporation in collaboration with the YUHS and implemented within the Korean Export Processing Zone (KEPZ) medical cluster (The Guru, 2024). Chittagong was strategically chosen for its potential to function as a regional medical hub, integrating healthcare and industrial development within a single ecosystem. The vision of CYNC was to establish a flagship nursing college within the KEPZ medical cluster that would systematically cultivate highly skilled nurses and thereby elevate both regional and national healthcare standards.

To realize this vision, YUCN was commissioned to provide comprehensive consultancy across the entire process between August 2023 and July 2025, ensuring the successful establishment and long-term sustainability of the college. This support encompassed the review of national standards for nursing colleges, guidance on approval and accreditation processes, planning of campus facilities and space allocation, curriculum design, development of faculty recruitment criteria, and formulation of student admissions policies. Collaboration with key stakeholders—including the Chittagong Medical University (CMU), the MOHFW, the Directorate General of Nursing and Midwifery (DGNM), and the BNMC—was also essential for obtaining regulatory approval and embedding CYNC within the national nursing education framework.

The established CYNC campus consists of two academic buildings and one dormitory, designed to provide an environment conducive to both learning and residential life. The college officially opened in July 2025, launching a four-year Bachelor of Science in Nursing (B.Sc.) program with an annual intake of 50 students (total 200 students across four cohorts). The program was developed in line with the BNMC’s latest standards, comprising an academic calendar of four years with 26-week semesters, six instructional days per week, and six hours of daily theory and laboratory instruction or eight hours of clinical practicum. Detailed course syllabi and practicum guidelines were prepared to ensure consistent delivery of both theoretical and clinical training.

The establishment of CYNC illustrates an innovative model of how private sector leadership, international academic expertise, and local governance can converge to address systemic health workforce shortages. Its creation is expected to strengthen the supply of qualified nurses in Chittagong, expand access to higher education for local students, and reduce regional disparities in healthcare human resources. Together with national-level institutions such as NIANER, CYNC highlights how government bodies, academic institutions, and private corporations can collaborate to strengthen health systems in LMICs through investment in nursing education.

Shields Nursing Education Program (SNEP)

In addition to the establishment of formal academic institutions such as NIANER and CYNC, a complementary initiative, the SNEP, was undertaken to strengthen the clinical competencies of Bangladeshi nurses through targeted training opportunities outside Bangladesh. The SNEP was implemented at YUHS under the leadership of its Department of Nursing, within the framework of the Avison International Fellowship in 2017 (YUHS Medical Mission Center, 2022). The program was designed to provide Bangladeshi nurses with intensive exposure to advanced healthcare practices in a high-resource setting.

Since 2017, the program has annually invited two Bangladeshi nurses to participate in a two-month intensive training course, with a total of eight nurses trained to date. The program covered multiple clinical departments, including pediatrics, obstetrics, the emergency department, intensive care units, and the disaster medical education center. Training encompassed both direct clinical practice and observation-based learning, with a particular emphasis on patient safety, infection prevention and control, and electronic medical record (EMR)-based nursing documentation. By situating nurses in highly specialized and technologically advanced hospital units, the program enabled participants to develop hands-on experience with modern clinical protocols and equipment rarely available in their home institutions.

A distinctive feature of the SNEP was its alignment with the healthcare needs of Bangladesh. While participants were introduced to global best practices in patient care and hospital management, the curriculum also encouraged critical reflection on how these practices could be adapted to the resource-constrained context of Bangladeshi hospitals. In this way, the program functioned not only as a skills transfer initiative but also as a platform for professional exchange, enabling nurses to contextualize learning and implement improvements upon returning home. The outcomes extended beyond individual professional development: participants expressed a strong commitment to disseminating their newly acquired knowledge and skills within their institutions, thereby creating ripple effects across local healthcare systems. Moreover, exposure to interdisciplinary teamwork and a culture of patient safety contributed to shifting professional attitudes, fostering leadership and evidence-based practice in their workplaces.

As a complementary initiative to the NIANER and CYNC, the SNEP demonstrates how short-term international clinical training can reinforce the objectives of long-term academic investment. By bridging advanced hospital practices in Korea with the realities of the Bangladeshi health system, the program contributed to building a cadre of nurses who are not only clinically competent but also capable of acting as change agents in their home country’s evolving healthcare environment.

LESSONS LEARNED AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR STRENGTHENING NURSING EDUCATION IN LMICS

Achievements in Bangladesh

The Bangladesh experience demonstrates that strengthening the nursing workforce requires simultaneous attention to both numerical expansion and qualitative enhancement of education. The establishment of institutions such as the NIANER and CYNC has significantly increased enrollment capacity at both graduate and undergraduate levels, thereby addressing the quantitative shortage of nurses. Most notably, NIANER emerged as the country’s first graduate-level nursing institution, introducing structured master’s programs that created a precedent for advanced nursing education in Bangladesh.

In parallel, initiatives such as the development of an IPC curriculum and short-term international training opportunities through the SNEP have contributed to qualitative improvements. These efforts enhanced clinical competencies, research skills, and leadership capacity while exposing Bangladeshi nurses to internationally benchmarked practices adapted to local system needs.

Faculty development further consolidated these achievements. Five Bangladeshi nurse educators successfully completed doctoral training at YUCN and returned to NIANER as academic leaders. Their contributions extended beyond teaching to include the advancement of research capacity in nursing, while joint research initiatives between Bangladeshi and Korean scholars generated publications on nursing, health systems, and disease-specific challenges. Graduate students were also supported to present at regional and international conferences, enhancing their academic visibility and professional confidence.

Taken together, these achievements illustrate that Bangladesh has progressed beyond the expansion of nurse numbers. Through a combination of institutional development, curricular innovation, faculty training, and opportunities for scholarly engagement, the country has laid the foundation for a workforce that is not only larger but also more skilled, research-competent, and capable of leadership in both national and international contexts.

Key Considerations for Strengthening Nursing Education in LMICs

The Bangladesh case highlights several considerations relevant to LMICs seeking to strengthen their nursing education systems.

1. Contextualized yet globally aligned curricula: Programs must remain responsive to national health priorities while maintaining alignment with international standards to ensure that nurses are competent to address both domestic and global health challenges (Davey, 2023).

2. Financial sustainability: Long-term viability requires diversified funding models, combining government allocations, international assistance, and private sector investment (Inaoka, 2024).

3. Integration of education and practice: Strong clinical training environments should be institutionalized by linking nursing schools with hospitals, community health centers, and primary care facilities to ensure that theoretical knowledge is consistently translated into practice.

4. Career development and retention pathways: Reducing workforce attrition necessitates strategies for continuing education, leadership development, and professional recognition (Malema et al., 2018).

5. Role of international partnerships as enablers: International partners should reinforce local systems and safeguard national ownership through long-term, context-sensitive support.

Beyond structural elements, cultural and social dynamics also shape workforce development. In many LMICs, including Bangladesh, nursing remains undervalued compared to medicine, contributing to challenges in social recognition and professional status (Joarder et al., 2021; Moghbeli et al., 2025). Advocacy, community engagement, and visible demonstrations of nurses’ contributions are therefore essential for elevating the image of nursing and attracting new entrants.

Political and administrative contexts—including governance structures, decentralization, and bureaucratic capacity—further influence the feasibility and pace of workforce reforms (Menon et al., 2025; s, 2019). Strengthening nursing education thus requires partnerships with national governments, ministries of health, and regulatory councils to ensure that reforms are embedded within institutional structures and aligned with broader socio-political contexts. Addressing these structural, cultural, and political dimensions in tandem creates the enabling conditions for workforce expansion and the elevation of nursing as a respected profession within LMIC health systems.

Recommendations for Policy and Practice

The lessons from Bangladesh carry several implications for both national policymakers in LMICs and international development partners:

1. Integration of nursing into national health strategies: Ministries of Health should position nursing education and workforce planning as core components of national health policies rather than ancillary professional development activities. Embedding nursing priorities within broader UHC and SDG strategies can elevate visibility and attract sustainable funding.

2. Faculty development as a cornerstone of sustainability: Expanding access to doctoral education and leadership training for nurse educators is essential. Without a cadre of highly trained faculty, the expansion of nursing schools risks outpacing the availability of qualified instructors. Investment in academic leadership ensures that workforce growth is accompanied by improved quality.

3. Strengthening governance and regulatory frameworks: Nursing councils and professional associations must be empowered to set accreditation standards, regulate practice, and ensure accountability. Strong governance structures reduce fragmentation and safeguard educational quality across institutions.

4. Leveraging partnerships strategically: Public–private partnerships, as demonstrated in Bangladesh, can mobilize resources and expertise while aligning with national needs. However, they must operate within a coherent governance framework to prevent inequities in access or duplication of efforts.

5. Harnessing digital innovations: The adoption of digital learning platforms, tele-mentoring, and simulation-based education can help address faculty shortages and extend access to quality training in resource-constrained settings. Such technologies should complement, rather than replace, in-person clinical training.

6. Fostering a culture of professional recognition: Elevating the social and professional status of nursing through advocacy, media engagement, and demonstration of nurses’ contributions to population health can improve recruitment, reduce attrition, and shift long-standing hierarchies in LMIC health systems.

By implementing these policy and practice recommendations, LMICs can move beyond temporary solutions and build sustainable nursing education systems that contribute to stronger, more resilient health systems.

CONCLUSION

The Bangladesh experience highlights the imperative of moving beyond short-term interventions toward the long-term construction of a resilient health workforce. Strengthening nursing education is critical not only for expanding the number of trained nurses but also for enhancing their competencies in clinical practice, leadership, research, and policy engagement. Sustainable progress requires that nursing education be firmly embedded within national health strategies, supported by international cooperation that prioritizes capacity building while respecting local contexts and governance structures. Looking forward, global solidarity and collaborative partnerships in nursing education will be essential to preparing nurses for evolving health challenges, including demographic transitions, emerging diseases, and the growing complexity of health systems.