Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > IGEE Proc > Volume 1(1); 2024 > Article

-

Article

Analysis on Coral Bleaching (Soft/Hard Coral) and Coral Ecosystem Restoration Strategies—Linkage to Sustainable Industries and Economic Valuation<sup>†</sup> - Nakyung Lim*, Haemin Choi

-

IGEE Proc 2024;1(1):102-118.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.69841/igee.2024.001

Published online: September 30, 2024

Department of Economics, Underwood International College, Yonsei University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

- *Corresponding author: Nakyung Lim, nklim0316@yonsei.ac.kr

- †The research focuses on soft coral communities in the Republic of Korea and coral reefs in Malaysia, supported by the Social Engagement Fund (SEF) 2023.

• Received: July 5, 2024 • Accepted: August 14, 2024

© 2024 by the authors.

Submitted for possible open-access publication under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 982 Views

- 25 Download

Abstract

- Among marine ecosystems, coral reefs play crucial roles in terms of ecological functions such as biodiversity protection and coastal protection and have significant economic value, estimated at approximately 2.7 trillion USD per year. However, the current state of coral reefs is alarming, with more than 93% of coral ecosystems being damaged primarily by human activity and climate change. In line with UN Sustainable Development Goals 13 and 14, this research aims to analyze coral bleaching in soft corals in Korea and coral reefs in Malaysia through field surveys and interviews to assess their current conditions. This study also explores strategies for the restoration of coral ecosystems, utilizing economic valuation methods such as the Toolkit for Ecosystem Service Site-Based Assessment (TESSA). Despite the limitations of applying a landscape-focused methodology to the marine environment and the lack of available data, this study emphasizes the importance of sustainable tourism and collaborative educational curricula involving governmental research institutes, universities, NGOs, and divers. These efforts are inspired by interactions with the Borneo Marine Research Institute (BMRI) at Sabah University and the Reef Check Center in Malaysia.

- Marine ecosystems play crucial roles as both resources and vital components that support human livelihoods. Covering approximately 70.8% of Earth’s surface, the oceans sustain the lives of 2.6 billion people who depend on them for various needs and are of paramount importance in terms of ecological functions, such as nutrient absorption, carbon dioxide sequestration, and global circulation effects. Coral reefs, often referred to as the ‘tropical rainforests of the sea,’ constitute only 0.2% of the ocean floor but are inhabited by 25% of marine species, harboring the most biodiversity in the ocean by serving as vital carbon sinks and producing oxygen (Brander, et al., 2012). According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce (NOAA), coral reefs provide direct use values (swimming, diving, snorkeling, and watching), indirect use values (coastal protection, providing habitats for commercial and recreational fisheries), and nonuse values (benefits associated with the natural ecosystem) (NOAA, 2021). Its ecology can provide considerable economic benefits to coastal residents, including the tourism industry, fishery resources, coastal habitat protection, and medical product research and development (R&D) (Cesar, et al., 2003).

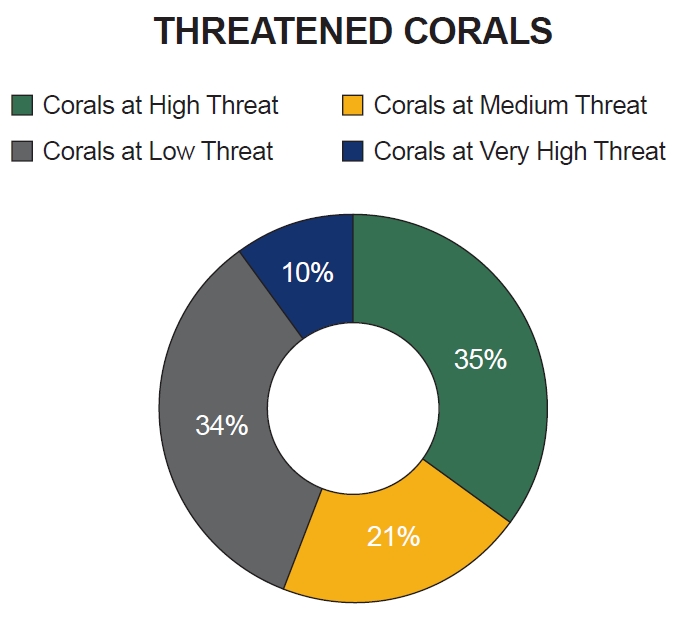

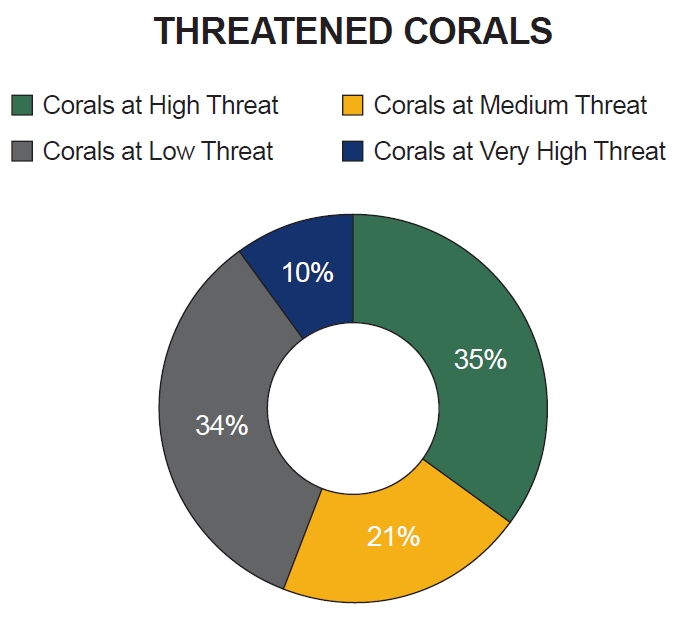

- The United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) noted that the economic value of coral reefs, which contribute to tourism, fisheries, well-being, coastal protection, marine biodiversity protection, medicinal compounds, etc., is estimated at 2.7 trillion USD per year (approximately 3729.4 trillion KRW annually) (UN Environment, et al., 2018). However, more than 93% of coral reefs have been damaged by human activities, along with climate change. Thirty to 40% of global corals are facing extinction within the next 30 years, and it is a looming possibility that corals would have gone extinct entirely by 2100, which would have a significant effect on human life (Scott, et al., 2022) [Figure 1].

- One of the easiest ways to grasp the magnitude of coral reef destruction is to analyze “coral bleaching.” Coral bleaching is a phenomenon in which corals turn completely white, which is caused mainly by increases in water temperature, pollutants, acidification, or abnormal weather, such as severe typhoons (NOAA, 2020). When corals expel the algae living in their tissues, also known as zooxanthellae, they lose their color. Once bleaching happens, the possibility of spontaneous recovery is slim. Considering the critical role of coral reefs, it is necessary to restore coral ecosystems in the long term. A number of factors are involved, but this study focuses on two axes: identifying the current conditions of corals, especially corals in Malaysia and the Republic of Korea, and understanding the significance of coral ecosystems via socioeconomic analysis.

- In doing so, the study demonstrates the legitimacy of considering restoring coral ecosystems and eventually delving into internally applicable solutions in terms of both what individuals can do and how domestic industries can approach the issue. Research would include evaluating the socioeconomic value of domestic coral communities via valuation through the progress of preliminary studies on coral reefs, onsite habitat examination, and data analysis. Although progress has been made in collecting and sharing marine data periodically, there are still limitations to research regarding domestic soft coral communities, designated natural monuments, especially with respect to the valuation and search for solutions from various angles. Few domestic studies have applied the Contingent Valuation Method (CVM) (Lee, 2018), a widely used stated preference method for evaluating environmental goods, to estimate the annual value of coral communities in the surrounding areas of Jeju's Moon Island and other nearby marine protected areas (Park et al., 2018).

- The study aims to lay the foundation for international collaboration beyond domestic efforts by cooperating with domestic and international organizations. This would ultimately foster sustainable tourism, expand support for coral conservation at the governmental and corporate levels, and establish educational curricula on marine ecosystems for the public and students [Table 1].

- In essence, the fundamental objective of this research is to contribute to a sustainable society where nature and humanity can coexist harmoniously, aligning with the United Nations (UN)’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 14 (Life Below Water) and 13 (Climate Action), as shown above. Although there has been some progress in expanding marine protected areas over the years, more concerted efforts and accelerations are urgently needed (UN General Assembly Economic and Social Council, 2023). By utilizing insights gained through conjunct meetings with experts from coral reef institutions in both Korea and Malaysia and field surveys, this study strives to address the points outlined in the SDGs and draw coordinated global action to advance toward sustainable ecosystems and societies.

1. Introduction

- Materials

- This research focused on coral reefs in Malaysia, which are part of the Coral Triangle, as well as soft coral communities in Korea. The Coral Triangle (CT) is a marine area located in the western Pacific Ocean, including waters of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Timor Leste and Solomon Islands. There are nearly 600 different species of reef-building corals alone in the area; over 120 million people reside there and rely on coral reefs for food, tourism, and protection from storms (WWF Coral Triangle Programme, 2023). Although corals inhabit various environments, including the subarctic region, temperate zone, and torrid zone, and even the abyssal sea, broad distinctions can be found among the species. Coral reefs are a class of hard corals and calcareous algae, mainly in tropical sea areas between 30 degrees of northern latitude and 30 degrees of southern latitude, which includes the CT. Diverse corals, such as hard corals and soft corals, inhabit Korea, but no coral reef has formed, such as in the tropical sea area, since the South Korea sea area is between 33 and 43 degrees of northern latitude. Rather, unique and unparalleled soft coral communities are built up, along with certain hard corals. Owing to its value and characteristics, the government has designated soft coral communities, ‘Natural Monument No. 442’, as marine biological communities in Korea. There are approximately 7,500 species of coral reefs worldwide, with over 170 species found in Korea (Shin, 2024). There is currently no massive stony coral reef cluster in Korea that can form coral reefs, which is why it is more accurate to use the term ‘coral community’ or ‘coal colony’ for soft corals in Korea and ‘coral reef’ for hard corals that mainly inhabit Southeast Asia or Australia, which the term ‘coral ecosystem’ covers these reefs.

- Methods and Analysis

- Given the lack of field-centered coral reef research in Korea, direct face-to-face meetings were conducted with experts actively engaged in coral reef work through a field survey at the National Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea (MABIK). For international research, a visit to Malaysia, a country actively conducting coral reef research, included visits to the coral reefs in Kota Kinabalu, meetings with experts from Sabah University, and discussions with Reef Check Center experts, providing insights into field-centered coral reef research and conservation.

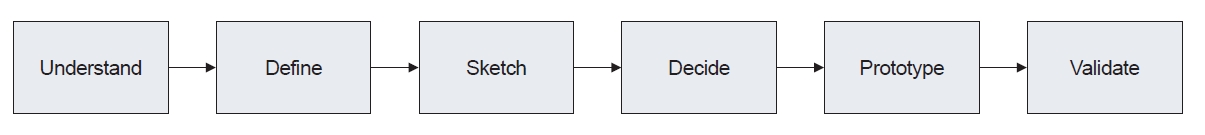

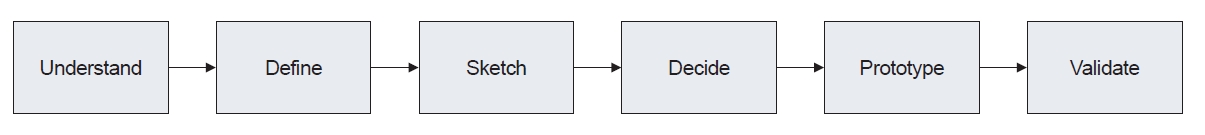

- A pilot study focused on enhancing social awareness for coral conservation through social media and an artificial coral design project, the ‘Green Wave Project’, which was supported by the Institute for Higher Education Innovation Yonsei University (IHEI). Through this activity, we identified key insights by reflecting on projects aimed at promoting social awareness for coral conservation. For the pilot study, Design Sprint Methodology by Google Ventures was applied, following the process below [Figure 2]:

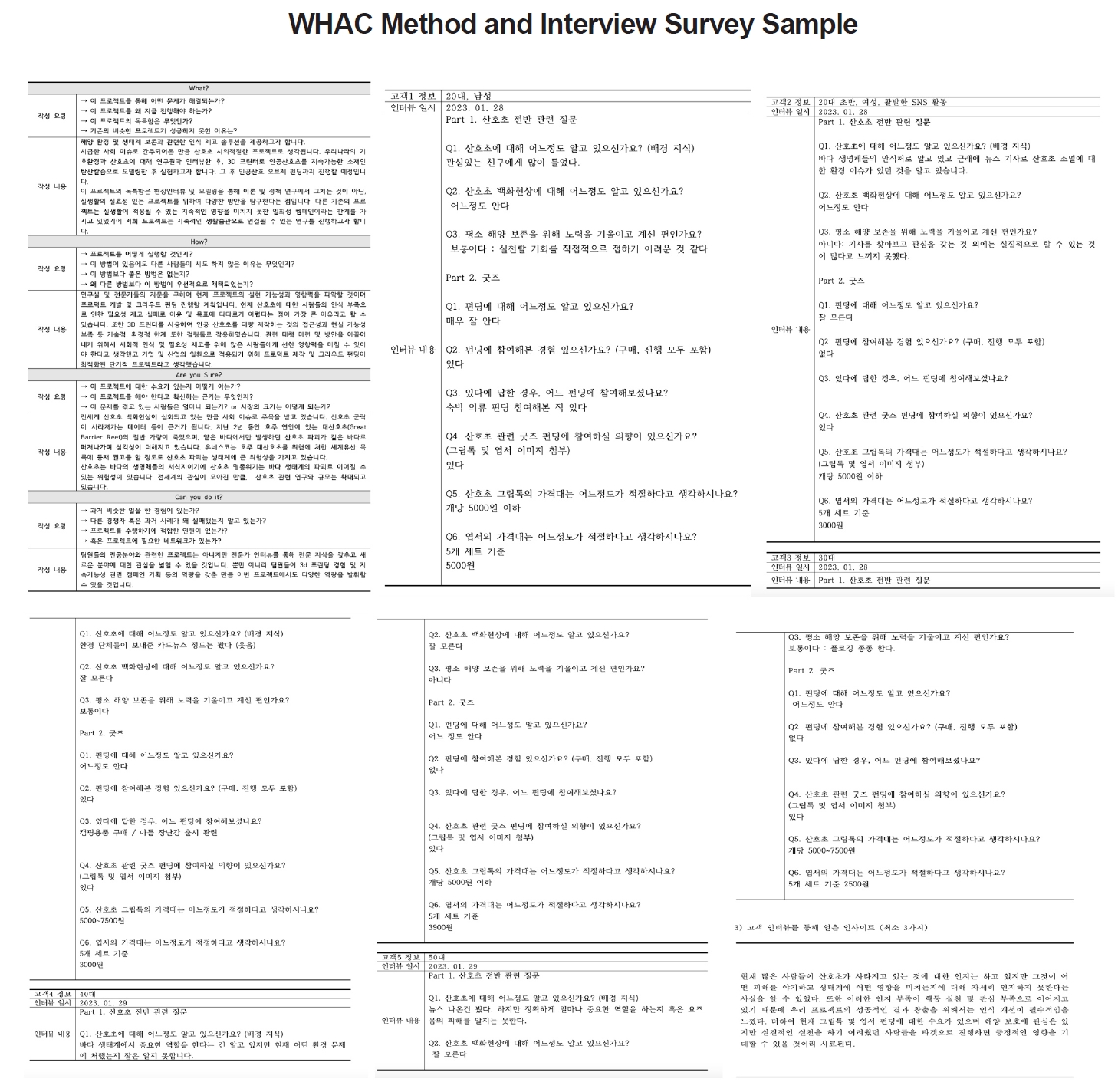

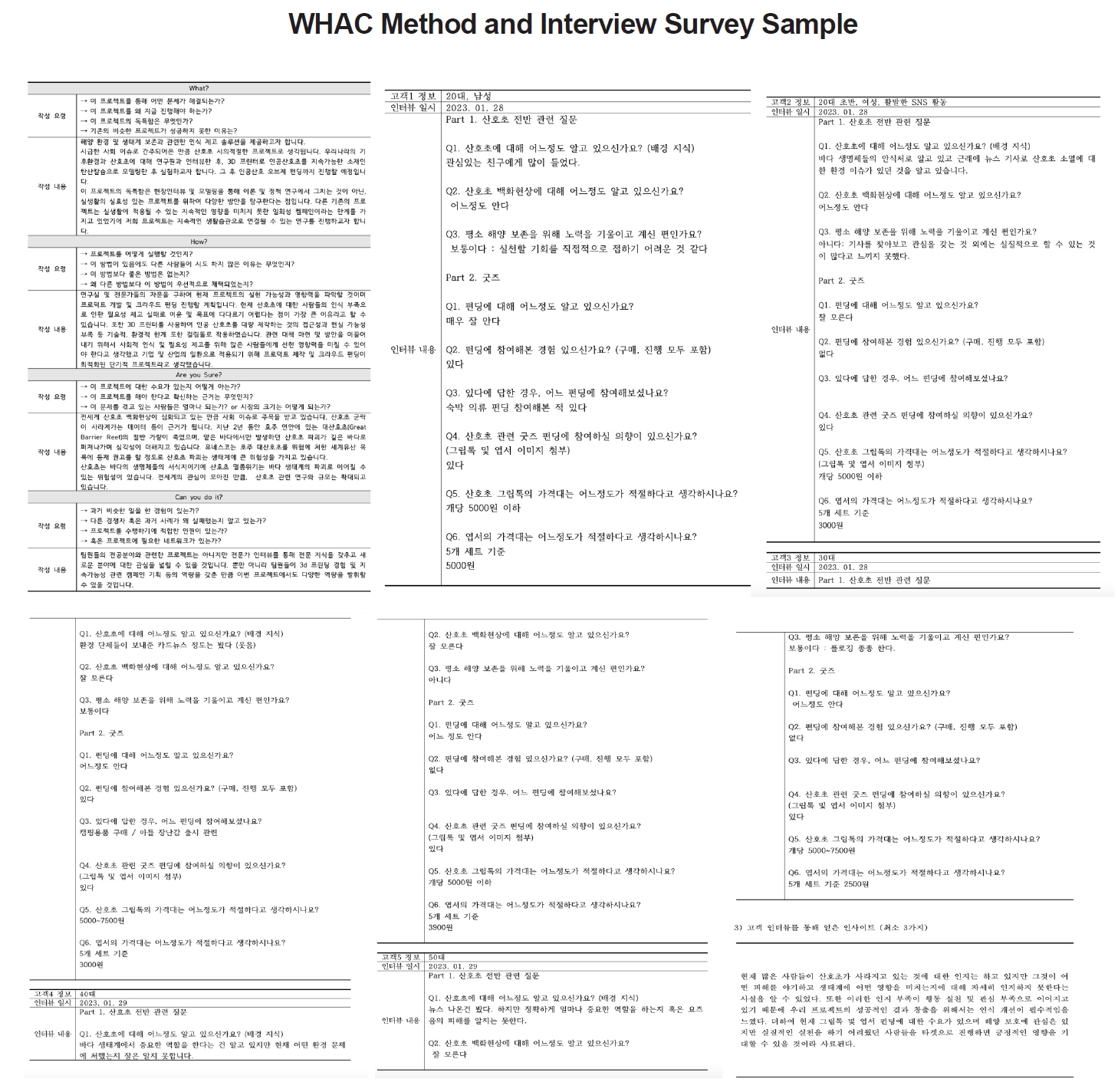

- The WHAC method (Pinvidic, 2019) was used to organize the information to convey it in a more structured way [Figure 3]. It includes ‘What,’ ‘How,’ ‘Are you sure?,’ and ‘Can you do it?’ as a component. The interviews were held to collect data on how much people are aware of coral bleaching, how to conserve the coral ecosystem, and how their willingness to pay for products to increase awareness. The interviews were conducted face-to-face, with two participants in each age range: 10--19 years, 20--29 years, 30--39 years, 40--49 years, 50--59 years, 60 years and above.

- We conducted weekly literature reviews during the study sessions to lay the groundwork for future research on coral reefs and ecosystem valuations. The literature includes reports from internationally recognized institutions contributing to coral research, such as the International Coral Reef Institute (ICRI) and NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program, as well as domestic and international research papers. By examining various domestic and international case studies, we have improved our understanding of coral distribution, research trends, and efforts for conservation and restoration.

- Throughout the study, meetings were held with experts, including Dr. Moon Hyewon at the MABIK and overseas experts Dr. Muhammad Ali Bin Syed Hussein, Dr. Mohd Fikri Akmal Bin Mohd Khodzori from the University of Malaysia Sabah Borneo Marine Research Institute (BMRI), and the Chief Programmes Officer Alvin Chelliah from the Tioman Island Office, Reef Check Center Malaysia. MABIK is responsible for the efficient conservation of domestic marine biological resources and is a comprehensive agency for the collection, conservation, management, research, exhibition, and education of marine biological resources (https://www.mabik.re.kr). The University of Malaysia Sabah BMRI is known for its focus on marine environmental conservation and sustainable fisheries (https://ums.edu.my/v5/index.php/en/8-general/2067-ipmb).

- We visited the Reef Garden in Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, to collect data on coral reef ecosystems and explore the CT.

- On the basis of preceding research, we referenced the methodology of choice experiments, grounded in the framework of maximizing expected utility, to conduct our study. To evaluate the value of restoring domestic coral reef habitats, we selected four attributes, including price attributes, and provided basic statistical metrics for these attributes (Park and Cho, 2018). An assessment of the economic value of protecting coral reefs has been conducted in several studies, and the Contingent Valuation Method (CVM) has been applied. The CVM is a method used to determine the value of nonmarket goods by setting up a hypothetical market and directly surveying consumers about their willingness-to-pay (WTP) or willingness to accept (WTA) needed. It is widely used to evaluate the value of environmental improvements, recreation sites, natural scenery, and places with cultural, historical, and ecological value. However, it is prone to errors in the analysis process because it estimates benefits on the basis of consumers’ self-reported WTP status in a hypothetical scenario (Kim, 2018).

- The compensating variation (CV), equivalent variation (EV), compensating surplus (CS), and equivalent surplus (ES) are the amounts of change in the level of utility, and WTP and WTA are the means of measuring the change in the level of utility (Oh, 2006). CV is the measurement method when utility increases, and EV is the measurement method when utility decreases; however, when the increase in service due to environmental improvement is not a continuous situation but an additional fixed amount is supplied, it is reasonable to measure the change in utility through compensating surplus and equivalent surplus (Freeman, 1979). The contingent valuation method directly asks the respondents to answer the difference between the expenditure (Y0) to maintain the initial utility level at the initial environmental quality level and the expenditure (Yi) to maintain the initial utility level at the changed environmental quality level, which is the CS, to measure the benefits of environmental quality improvement. Therefore, unlike the indirect benefit measurement method, the indirect benefit measurement method does not involve the complex intermediate process of making general assumptions about the utility function or deriving the ordinary demand function but directly derives the maximum WTP, which is the compensating surplus for environmental quality improvement, from the expenditure function. CS is defined as the expenditure necessary to maintain the initial utility level at the initial environmental quality level minus the expenditure necessary to maintain the initial utility level at the improved environmental quality level.

- CS = E(p, q0; U0, Q, T) - E(p, qi; U0, Q, T)

- p: vector of prices of market goods,

- q0: initial environmental quality level,

- qi: changed environmental quality level,

- U0: initial utility level,

- Q: vector of other public goods that are assumed not to change,

- T: vector of variables reflecting the preferences of participants

- In the above equation, the value of the first expenditure function is Y0, which is the minimum expenditure level of the participants' current income to obtain the utility U0 at the initial environmental quality level q0 under the given other conditions, and the value of the second expenditure function is Yi, which is the minimum expenditure level that can maintain the initial utility level U0 when the environmental quality level changes to qi under the given other conditions. At this time, CS, which is the WTP, is defined as the difference between Y0 and Yi. This can be expressed as a WTP function for the measurement of the benefits of environmental quality improvement, as shown below.

- WTP(qi) = f(p, qi, q0, Q, Y0, T)

- The respondent's willingness to pay is influenced by the prices of market goods (p), the initial environmental quality level (q0), the changed environmental level (qi), the level of unchanged public goods (Q), the preferences of the respondents (T), and the current income (Y0). The WTP function serves as the theoretical basis of the CVM as a value measurement function that expresses the economic welfare change due to the change in environmental quality (qi) in monetary terms.

- There has been much discussion in Korea about the use of the CVM to evaluate the value of environmental resources. Recently, in addition to tourism, various topics, such as the environment, health, arts, and education, have been the subject of studies applying CVM, with diverse research results presented (Kim, 2018). To overcome this limitation, we utilized the Toolkit for Ecosystem Service Site-Based Assessment (TESSA) [Table 2], which serves as an accessible guide for evaluating benefits received from nature at specific sites, offering low-cost methods and generating information that can influence decision-making processes (Peh, 2013).

2. Materials and methods

Participants:

Measures and Analysis:

1) Pilot study analysis

2) Literature Review and Case Studies

3) Expert Consultation

4) Field surveys

Models:

- Analysis of the Pilot Project

- In the pilot study, limited domestic social awareness regarding coral ecosystems was identified, leading to the design of a prototype product that effectively communicates coral ecosystem protection.

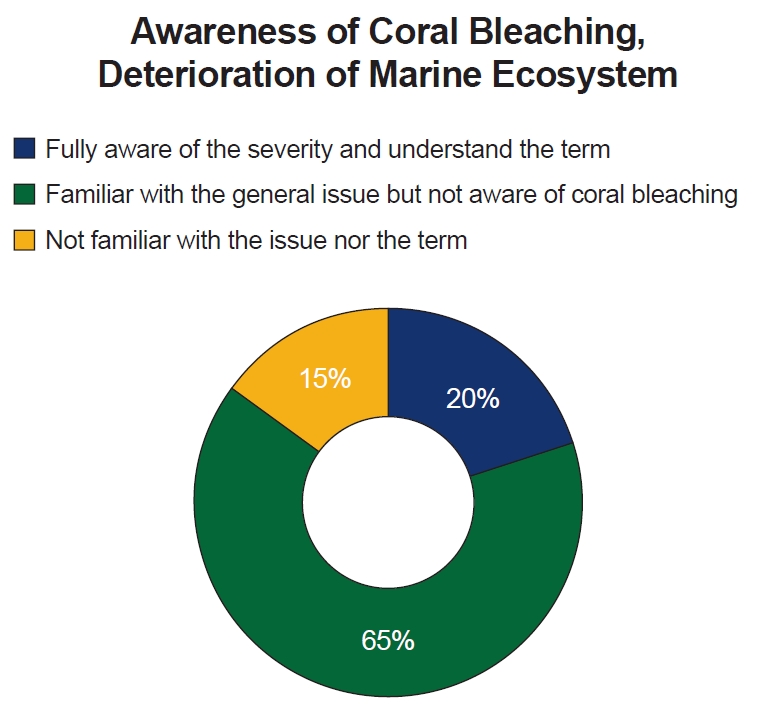

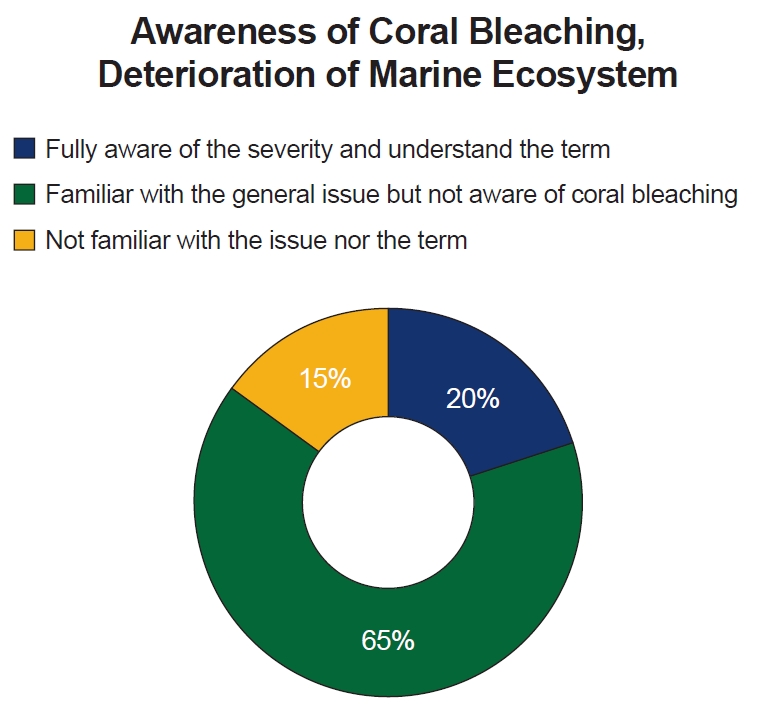

- With respect to the awareness of coral bleaching and the destruction of the marine ecosystem, approximately 65 percent of them were aware of the issue of the deterioration of the marine ecosystem but were not familiar with the term ‘coral bleaching.’ Twenty percent of them were familiar with the issue and highly aware of it, and 15 percent were not aware of the issue or the term. Approximately 70% of them were not aware of the methods used to practice marine ecosystems or coral restoration and were open to products or education on relevant issues. With respect to the products used to raise awareness, over half of the interviewees had a high preference for PopSockets, following informative postcards or brochures. Approximately 65 percent would be willing to pay between 7,500 and 10,000 KRW for the product. Twenty percent were willing to pay between 5,000 and 7,500 KRW, 10 percent were willing to pay more than 10,000 KRW, and 5 percent were willing to pay less than 5,000 KRW [Figure 4].

- To foster general awareness, we designed prototype products and registered them on online channels, making them accessible to the public. Along with the prototype product, we created and shared articles on social media highlighting coral and marine ecosystem content.

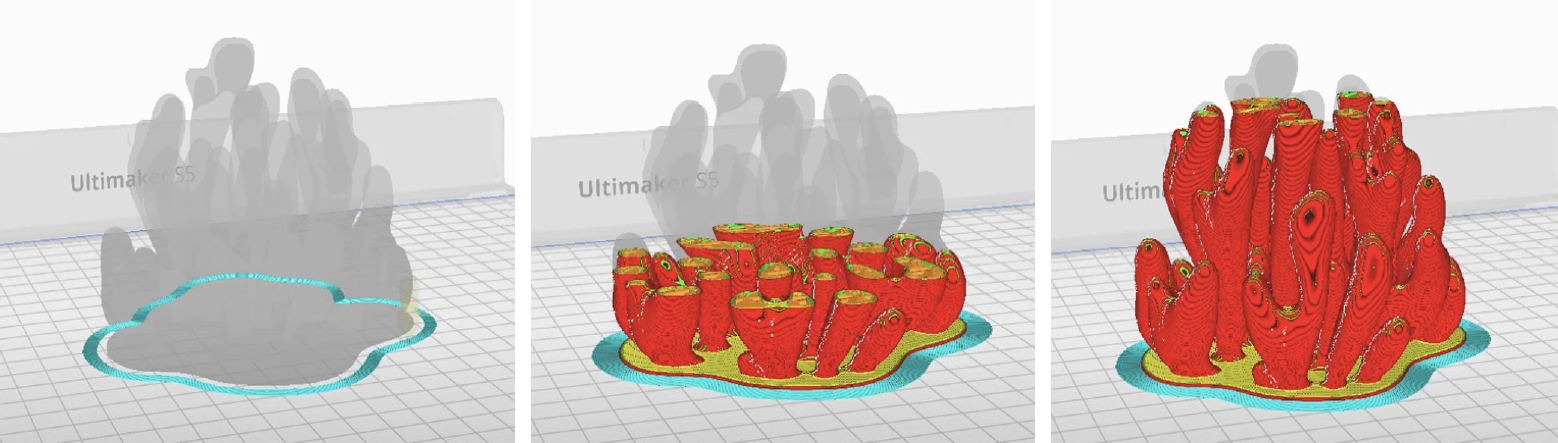

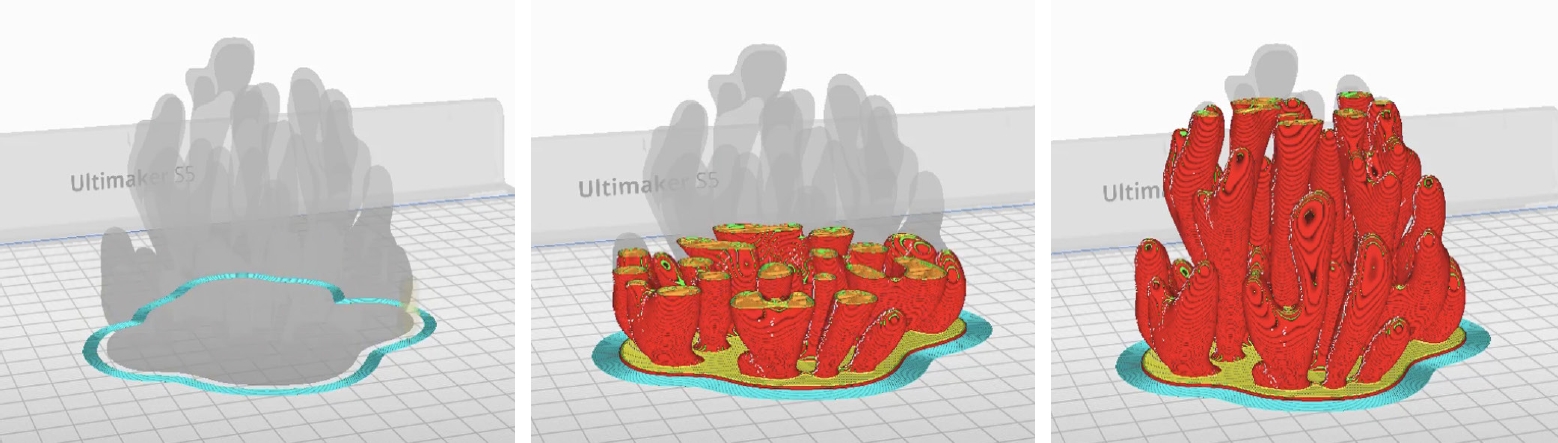

- Additionally, we explored alternative methods for creating artificial coral reefs via 3D design programs to protect coral reefs damaged by excessive tourism. Artificial coral reefs are man-made structures that are placed in the ocean to mimic the functions of a natural reef. It has the potential to serve the same role as natural coral reefs, promoting ocean biodiversity, protecting shorelines from erosion and storm surges, increasing the local fish population, and providing the right environment for algae growth (CyBe Construction, 2023). We can recognize the importance of artificial coral reefs and search for sustainable materials or structures during production. Divers are actually willing to contribute to all increases in reef community attributes and are partially able to discriminate between them. Understanding the fundamentals that constitute a coral reef community and the value of its diversity may have a social impact on the design of marine reserves and preplanned artificial reefs (Polak, 2013).

- The 3D design was based on a discussion of the circular design and material approach (Thy, 2021). Modeling of artificial coral reefs was performed to investigate the feasibility of producing them through 3D modeling and printing and eventually to explore the utility of the artificial coral reefs produced. The printing process was based on the plan in Yonsei University International Campus Makerspace, which is operated under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of SMEs and Startups. We initially planned to create environmentally friendly artificial coral reefs using calcium carbonate, but a 3D printer that is capable of using calcium carbonate as a printing material was not available. Nonetheless, we successfully completed the slicing process, converting the 3D modeling into G-code via a 3D printer that can produce using filaments only [Figure 5].

- Analysis of the Current Conditions of the Coral Ecosystem

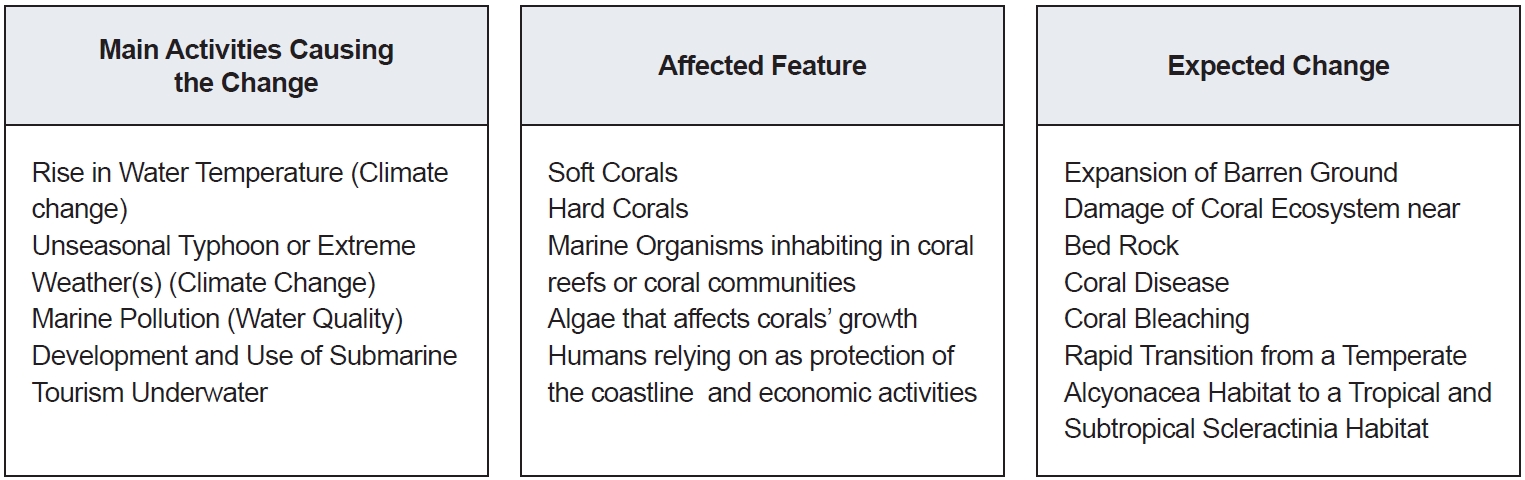

- According to the UN SDG progress report, ocean acidification is increasing and will continue to do so if carbon dioxide emissions continue to rise, threatening marine ecosystems and the services they provide. The current ocean’s average pH is 8.1, which is 30% more acidic than it was in preindustrial times (UN General Assembly Economic and Social Council, 2023). For the domestic marine environment inhabited by soft corals, over the past 50 years, the surface temperature of Jeju's waters has increased by 1.23°C, which is more than twice the global average increase of 0.48°C (https://www.nifs.go.kr). An increase in temperature does not necessarily lead to the rapid expansion or disappearance of coral habitats. Corals that have acquired genetic factors for adapting to high temperatures can survive even with rapid temperature increases, whereas those that lack such factors either move to deeper waters or migrate northward to find suitable habitats. Vulnerable species, such as night coral, may experience drastic declines in population due to temperature increases. Among various patterns, the rapid spread of Montipora digitata coral is particularly notable. This hard coral species occupies areas where representative seaweeds of Jeju's waters, such as kelp, have disappeared. Additionally, the competition between Alcyonacea and hard corals expands the overall habitat area. In other words, the marine environment of Jeju is rapidly transitioning from a temperate Alcyonacea habitat to a tropical and subtropical Scleractinia habitat (Shin, 2023).

- Analysis of SDG progress

- Through the analysis of SDG progress, this study aimed to improve the educational curricula. In fact, among 100 national curriculum frameworks, 47 percent do not mention climate change, and although 95 percent of teachers recognize the importance of teaching about climate change severity, only one third are capable of effectively explaining its effects in their region (UN General Assembly Economic and Social Council, 2023). Without addressing climate change, it would be impossible to address the issue of coral bleaching or the deterioration of marine ecosystems.

- With respect to SDG target 14.a, only 1.1 percent of national research budgets were allocated to ocean science on average between 2013 and 2021, although the ocean contributes to 2.5 percent of the world’s growth value added. The UN Ocean Decade, a global ocean exploration, research, and capacity-building project involving all UN member countries, was implemented from 2021--2030. In the field of marine and fisheries in Korea, there is a need for strategic expansion of support to secure a leading position in the rapidly changing marine and fisheries sector, as investment in international cooperation is relatively low compared with that in other sectors. Owing to the nature of ocean research being predominantly public research and the weak industrial base in the fisheries sector, there is a lack of commercialization of research and limited public perception of the effectiveness of R&D investment (Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, 2022).

- Visits to the MABIK and Expert Consultation

- We have visited the MABIK located at 75 Jangsan-ro 101beon-gil, Janghang-eup, Seocheon-gun, and Chungcheongnam-do and conducted an interview with Dr. Moon on the topic of "Cnidarians and Corals." We thoroughly investigated the biological classification system of corals, the taxonomic position of Cnidarians, the morphology and functions of Cnidarians, the class Anthozoa, the importance of corals, the characteristics and diversity of coral communities in Korea, a comparative analysis of coral species, the vertical distribution of coral clusters in Jeju, changes in coral resources and management strategies in response to climate change (global trends and bleaching phenomena, coral diseases, climate change hotspots, changes in the diversity of domestic corals due to climate change) [Figure 6].

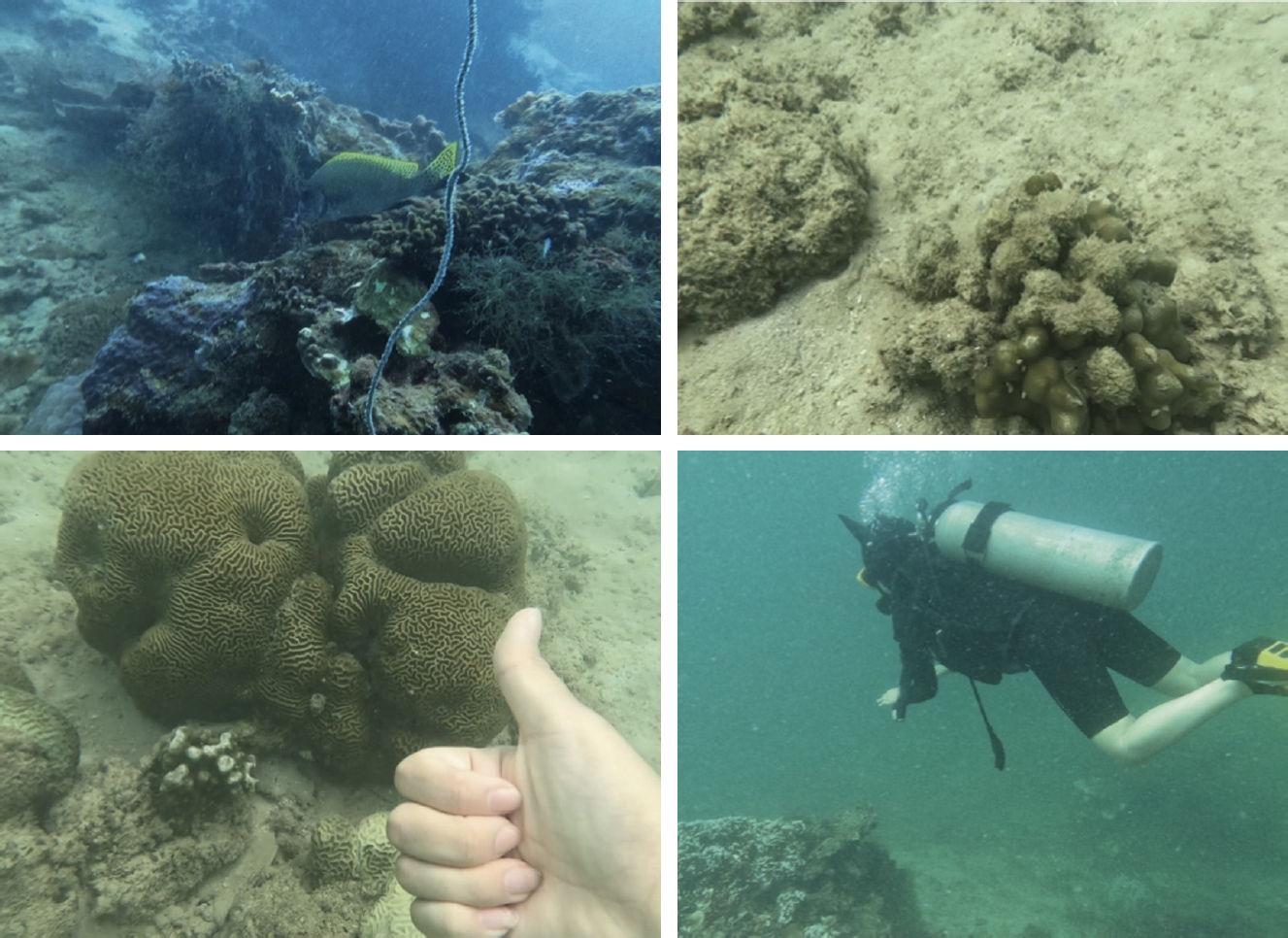

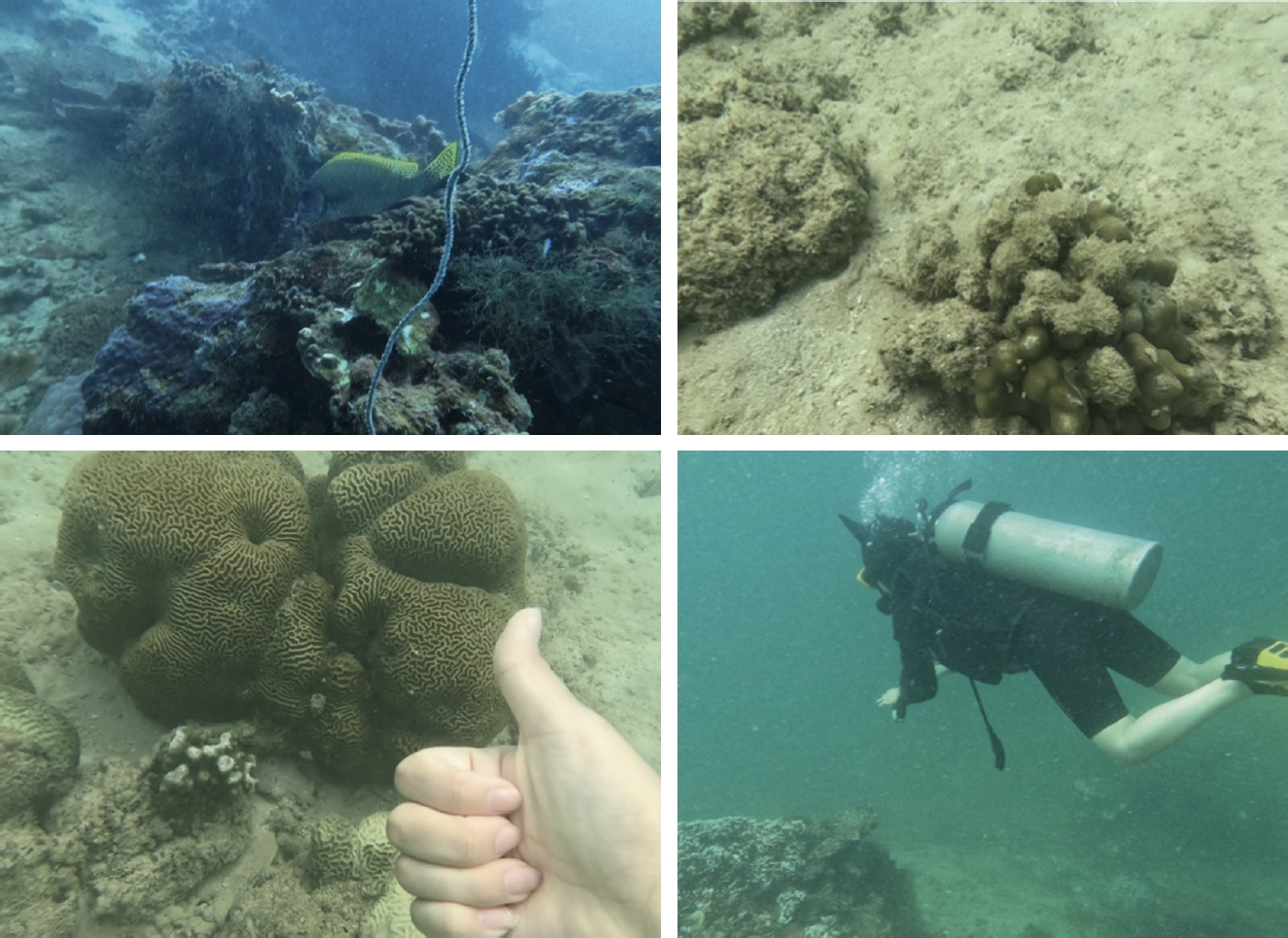

- Overseas Research Progress

- A marine field survey was conducted to directly observe the coral reefs at Kota Kinabalu Reef Garden, a coral triangle area in Malaysia. Through scuba diving and snorkeling, we confirmed the distribution of the coral reef ecosystems and collected videos and photographic materials. Through interviews with professional divers, we were able to conduct a vivid onsite investigation, including investigations of the status of coral reefs [Figure 7].

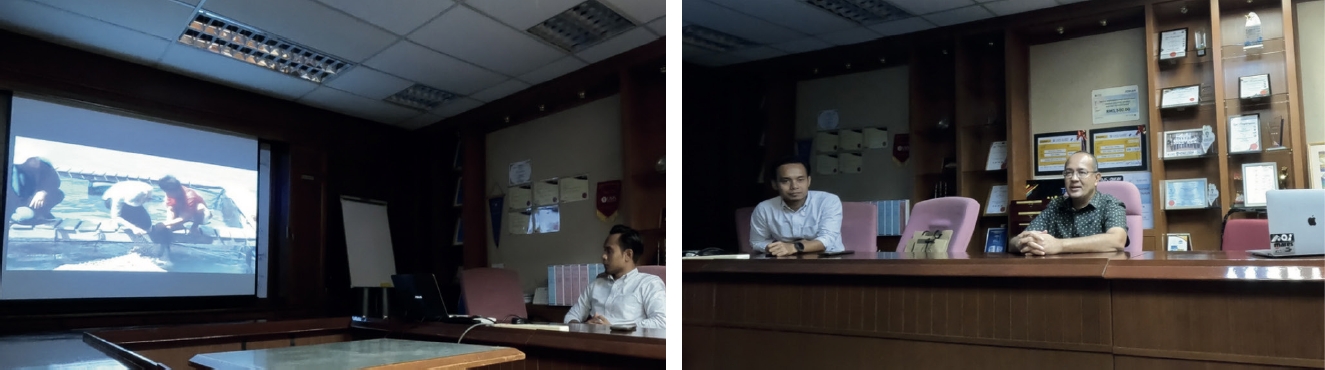

- During the research, we visited the University of Malaysia Sabah, which is known for its expertise in coral research and restoration [Figure 8]. There were meeting sessions with Dr. Muhammad Ali Bin Syed Hussein and Dr. Mohd Fikri Akmal Bin Mohd Khodzori, experts from the University of Malaysia Sabah BMRI, who are highly knowledgeable about coral disease and coral restoration. Insights into a wide range of topics, including the current state of coral reefs in Malaysia, the impact of climate change on coral reefs in the Kota Kinabalu region, coral diseases, and the conservation efforts of the Malaysian government, were gained. The experts mentioned that human activities, such as fish bombings, are the most influential factors affecting coral reefs in Malaysia. Therefore, there is a need for the coexistence of human activities and marine ecosystems, and efforts should be made to apply this understanding to research. The importance of Malaysia's marine ecosystem has been recognized, attracting approximately 20 million tourists annually, and the need for conservation efforts has been identified (Bin, 2018).

- Through online meetings with Alvin Chelliah, an expert from the Reef Check Centre of Malaysia, which monitors the condition of coral reefs for sustainable coexistence, we learned about the establishment and key activities of the Reef Check Centre. Research on coral reefs in Malaysia has allowed us to gain new insights into underwater data collection and management methods for corals, ways to utilize these methods domestically, and the possible process of establishing a reef check center in Korea. Furthermore, the study could reach an agreement to request and collaborate on underwater data in the future. There is a significant need for the establishment of a specialized coral reef institution in Korea, and the importance of increasing interest in coral reefs is a prerequisite for this.

- According to the interviews [Table 3], the underwater data collection categories included (1) fish, 9 types of bioindicators; (2) 9 invertebrates; (3) substrates of 5 living, 5 nonliving organisms; and (4) human impacts (coral disease, dynamite, fish bombing, and marine trash). Coral reef monitoring can be performed via basic Excel and statistical tools, as well as underwater notes, without the need for separate software. The data and analysis results are shared through annual reports and collaborations with expert groups and universities, which are used mainly in Malaysia's fisheries and tourism industries. We also learned that when government-led collaborative research is conducted, there is a high demand for data collection and analysis on an ongoing basis [Figure 9].

- In the Sabah region of Malaysia, there is an ‘education tourism’ program that combines adventures, education, and services to provide tourists or students with the opportunity to experience new experiences, cultures, and environments (Kim & Oh, 2017). This study concludes that this has significant implications for planning domestic educational tourism programs. Linking education and tourism industries with a focus on the environment and ecosystems will greatly contribute to sustainability. We found that domestic programs do not include coral-related educational courses, and by incorporating the cases of Sabah and the BMRI institution, it will be possible to create a curriculum that generates social impact [Table 4].

- Data analysis and valuation

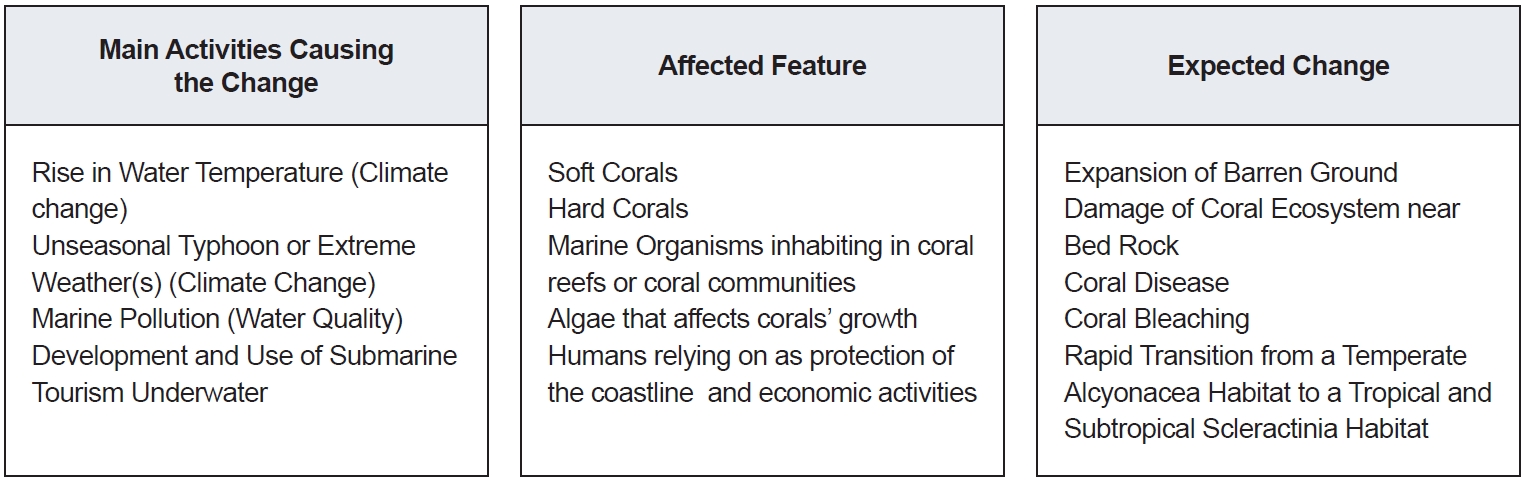

- We used TESSA to evaluate the value of the coral communities, aiming to establish new policies or apply comprehensive strategies for coral conservation in Korea, as the current policies are insufficient, as mentioned above [Figure 10]. In the preparatory stage, we conducted a valuation by defining the purpose of the evaluation, the evaluation area, and factors for communicating the results. The factors that influence the coral community on Jeju Island were subsequently analyzed, and their impacts were quantified, describing the changes in the community caused by these factors. However, owing to the limitation of collecting data on the coral community on Jeju Island, we encountered constraints in conducting an accurate valuations and plans for further research before reassessment. Nevertheless, attempting to evaluate the value of the domestic coral community, which has not been previously studied, and analyzing the factors and their impacts on the current domestic coral community have meaningful implications. Table 4 highlights the main activities causing the change, affected feature, and expected change. The activities mentioned in Table 5 demonstrate how related activities affect coral ecosystems, ranging from 0--5, adding up the timing, scope, and impact.

3. Results

1) Necessity for improvement of the educational curriculum

2) Critical Analysis of the Research and Development Budget and Investment

1) Marine Field Survey

2) Expert Consultation at the University of Malaysia Sabah BMRI

3) Expert Consultation of Reef Check Centre Malaysia

4) Related Literature Research

- Outcomes of the project

- The imminent threat of extinction facing 93% of endangered coral reefs by the year 2100, primarily due to human activities, underscores the collective responsibility of the global community in coral reef conservation. While there is growing international interest in coral reefs and marine conservation, domestic research in this field is lacking compared with global standards. Therefore, efforts have been directed toward domestic coral reef conservation and economic value estimation research, ultimately striving to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 14 for a sustainable marine ecosystem. Through paper studies, understanding the value of coral reefs in the natural world and initiating discussions on research collaborations with specialized coral reef institutions both domestically and internationally, specifically in Malaysia, the potential for international research cooperation in coral reef-related studies has been explored. Furthermore, continued research must parallel government and institutional support for sustainable tourism and work toward practical collaboration and social impact for the coexistence of humans and marine ecosystems.

- Through regular study sessions, we have gained insights into climate change and the economic value of ocean resources. On the basis of this foundation, the suitability of tools for measuring the economic value of coral reefs was explored through field surveys, interviews with practitioners, and data analysis. The focus was on economic evaluation, confirming its feasibility. Compared with domestic efforts, Malaysia demonstrated active collaboration with government bodies, educational institutions, and international NGOs such as the Reef Check Center. This collaboration encompassed monitoring, cooperative research, education, and restoration initiatives.

- Through the pilot study, we highlighted the necessity of raising awareness of coral bleaching and the importance of coral restoration and have approached various strategies for coral conservation via 3D modeling. The following research holds significance not only for sustaining coral conservation projects but also for developing them from a research perspective. This study provides an opportunity to expand the research scope beyond the goal of increasing awareness of coral conservation to devise approaches that can have substantial social impact. The project considered efforts at both research and educational institutions, increasing its significance. It was not limited to short-term interest but aimed to devise concrete and more realistic measures for coral reef conservation through sustained interest and research on coral reefs. Collaboration discussions with experts led to the pursuit of more specialized research, resulting in valuable insights.

- The study conducted collaboration discussions with specialized coral ecosystem institutions. Discussions with Dr. Moon of the MABIK and meetings with Malaysia's Sabah State University's BMRI and Reef Check Center Malaysia explored potential research collaborations for additional support in the future. As the research topic involves a need for both domestic and international collaboration, discussions were held with specialized institutions domestically and internationally. Positive feedback was received, particularly from the Reef Check Centre in Malaysia, in terms of data collection and cooperative analysis. Collaborating with Malaysia, where more active discussions in the coral reef field take place, laid the foundation for the future international development of the project.

- Suggestions for Sustainable Management

- Despite possessing globally unprecedented coral reefs in soft coral communities, research related to coral reefs in South Korea has not been actively conducted. Through discussions with Dr. Moon, it was confirmed that research on the valuation of coral in our country, where coral tourism is not well developed, has not been undertaken. Recognizing the need for value measurement as coral research progresses, a direct estimation of the economic value of the soft coral communities on Jeju Island was conducted. This highlights the importance of improving accessibility to domestic coral reef-related data and increasing awareness of the importance of data collection and management for value estimation. The study served as an opportunity to reinvigorate the timeliness of awareness enhancement in coral restoration and to establish directions for the development of educational processes.

- MABIK and the Reef Check Center of Malaysia share common concerns. Considering that factors such as global warming and rising sea temperatures led to the discovery of tropical corals in Korea, both institutions can play crucial roles in contributing to continuous monitoring and coral species research. This presents an opportunity to move beyond limited research on domestic coral ecosystems and establish more expansive and sustainable international collaboration. While tropical corals are not prevalent in Korea, the existence of the Reef Check Center has become more relevant because of changes in biodiversity caused by factors such as global warming. It is expected that they will play a significant role as hubs in international research collaborations.

- The severity of global warming, as evident through coral bleaching, directly highlights the urgency of addressing environmental issues. However, owing to their limited accessibility, domestic coral ecosystems often go unnoticed, leading to a lack of awareness of the impending crisis. Through onsite meetings, soft coral communities rapidly disappeared, and tropical corals were found even in the East China Sea region. The environmental changes in the marine ecosystem, discoverable domestically, go beyond a simple reduction in biodiversity and should be addressed as a serious environmental issue. This study laid the foundation for the following protective and restorative strategies: active and indirect restoration (Burdett, 2024). Recognizing the limitations of participation in lengthy research instead of collaborative projects, the periodic sharing of collaborative projects and issue status can facilitate swift responses to monitoring.

- As a research topic that is connected to various fields, such as fisheries and tourism, consideration of the sustainability of linked industries is expected. Coral reefs play a significant role in tourism, and addressing existing issues in sustainable tourism, production, and fisheries is crucial for preparing strategies for the future. By strategically targeting the lack of data analysis centered around domestic coral reefs, measuring economic value, and proposing ways to link this to sustainable industries, this study aims to provide insights for the government, businesses, and individuals to create a sustainable living environment as social entities. Moreover, efforts will be made to continue research and raise awareness through practical initiatives, including planning 'educational tourism' programs related to coral reefs by incorporating international cases.

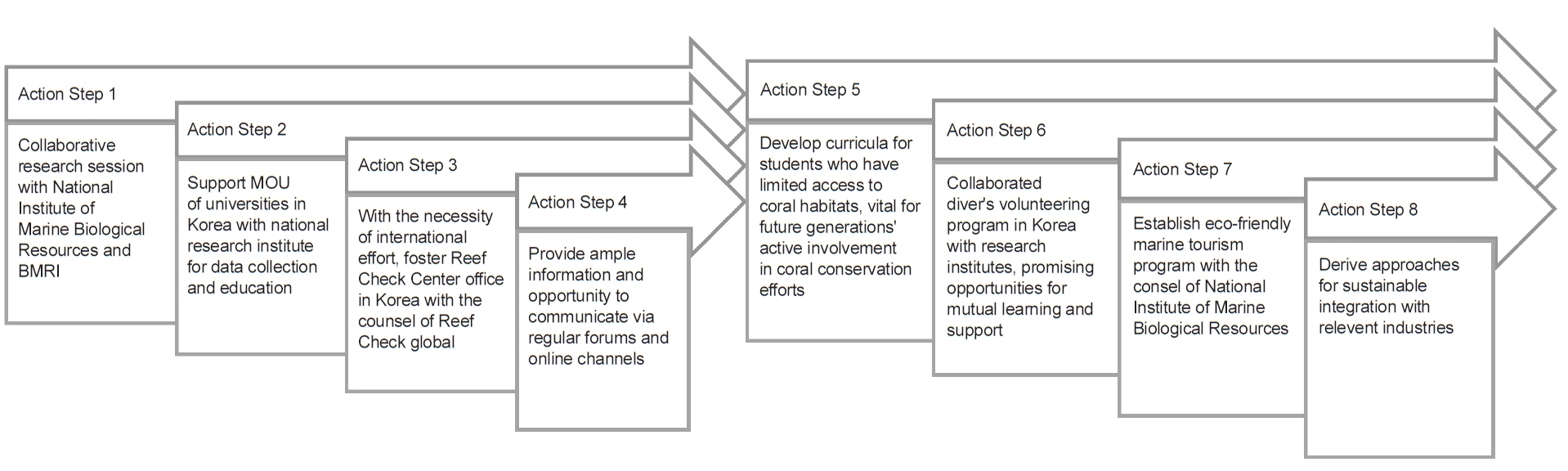

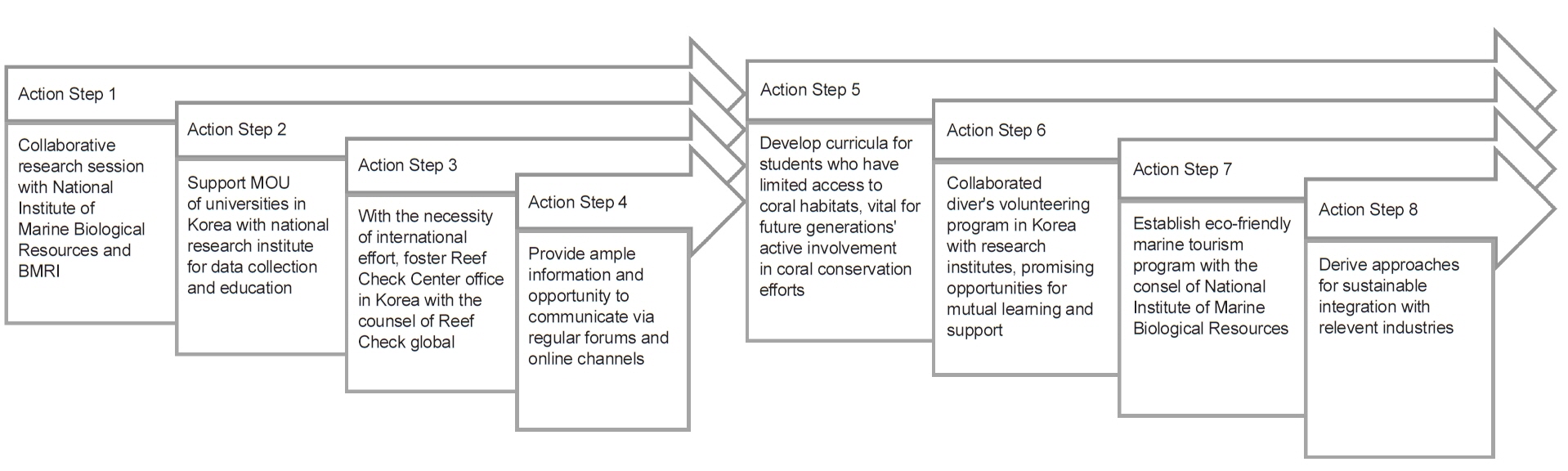

- Both Sabah University's BMRI, known for its expertise in coral research and restoration, and Reef Check Center Malaysia, recognize the urgency and necessity of collaborating with Korea on coral research. The conclusion drawn by the research is that, rather than focusing on sustainable industry linkages, more detailed coral monitoring, research, and education should take precedence. Therefore, along with introducing the establishment of Korea's Reef Check Center, future collaboration opportunities are anticipated through agreements with universities and government-affiliated research institutions. Policies can be subsequently aligned with educational curricula and research development. The development of a curriculum targeting students with low accessibility to coral ecosystems will be essential for the conservation of coral habitats by future generations. The study aims to contribute to communication platforms even after the project concludes to ensure continued impact, as shown in the action plan below [Figure 11].

- Limitations and Areas for Improvement

- The utilization of the TESSA method for estimating the economic value of domestic coral reefs faces challenges because of insufficient data from previous studies. The lack of comprehensive data, particularly on the composition and species variations of Jeju Island's fringing reef, poses a problem for the accuracy of the evaluation. The toolkit is used mainly for landscape or wetland ecosystems, and a more systematic approach reveals the ongoing need for additional data. In future studies, we expect to conduct experiments to examine the feasibility of educational curricula and cooperate with various stakeholders, including universities, research institutes, NGOs, and international organizations, for more stereoscopic and in-depth research, eventually seeking sustainable marine ecosystems with healthy coral communities.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Table 1.Related SDGs, Specific Targets, and Indicators of Each Goal (https://sdgs.un.org/goals)

Table 2.Overview of the TESSA process (Peh, 2013)

Table 3.Subsection of Interview

Table 4.Sabah Tourism Category (Kim and Oh, 2017)

Table 5.TESSA Applied to a Coral Ecosystem

- Bin, L. C., Salleh, N. H. M., & Bin, L. K. (2020). The evaluation model for coral reef restoration from a management perspective for ensuring marine tourism sustainability. Journal of Sustainability Science and Management, 15(1), 93-104. http://agris.upm.edu.my:8080/dspace/handle/0/19840

- Brander, L. M., Rehdanz, K., Tol, R. S., & Van Beukering, P. J. (2012). The economic impact of ocean acidification on coral reefs. Climatic Change Economics, 3(01), 1250002. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2010007812500029Article

- Burdett, H. L., Albright, R., Foster, G. L., Mass, T., Page, T. M., Rinkevich, B., & Kamenos, N. A. (2024). Including environmental and climatic considerations for sustainable coral reef restoration. PLoS Biology, 22(3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002542Article

- Cesar, H. (2003). Economic value of Egyptian Red Sea coral reefs. EEPP-MVE (Monitoring, Verification, and Evaluation Unit of Egyptian Environmental Policy Program). USAID Egypt. Available from https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnadf666.pdf

- CyBe Construction. (2023). Man made coral reefs with 3D concrete printing. CyBe Construction. Available from https://cybe.eu/solutions/artificial-reef/

- Freeman, A. M. III. (1979). Benefits of environmental improvement: Theory and practice. GV.

- International Coral Reef Initiative. (2018). The coral reef economy: The business case for investment in the protection, preservation and enhancement of coral reef health—Executive summary.

- Google Ventures. (2023). The design sprint. Google Ventures. Available from https://www.gv.com/sprint/

- Kim, D. K., & O, H. (2017). KCTI overseas business trip report: Foreign case studies on the evaluation of regional tourism development projects. KCTI. Available from https://www.kcti.re.kr/web/board/boardContentsView.do?miv_pageNo=2&miv_pageSize=&total_cnt=&LISTOP=&mode=W&contents_id=51131209f2fc4b92877c39a651e5c6fe&board_id=2&report_start_year=&report_end_year=&cate_id=160bcb16c21d471a9509cf3a41cb70e0&etc10=&searchkey=ALL&searchtxt=&link_g_topmenu_id=15f51238586a425981abe0b5f685d43a&link_g_submenu_id=0382ccddbde44a91bd57a705ed56aade&link_g_homepage=F

- Kim, Y. M. (2018). A study on estimating the value of world national heritage resource by contingent valuation method. Department of Tourism Development Jeju National University. USAID Contract No. LAG I-00-97-00015-00.

- Lee, C. H., Chen, Y. J., & Chen, C. W. (2019). Assessment of the economic value of ecological conservation of the Kenting coral reef. Sustainability, 11(20), 5869. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205869Article

- MetroEconomica, The Ocean Foundation, & WRI Mexico. (2021). Economic valuation of reef ecosystems in the MAR region and the goods and services they provide. Final report of Inter-American Development Bank. Contract No. RG-T3415-P002.

- Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries. (2022). Final report on the "Establishment of International Marine Science Cooperation Infrastructure" research and development project under the "International Marine Science Research" program. National Institute of Fisheries Science.

- National Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea (MABIK). (2023). Available from https://www.mabik.re.kr/kor/sub06_01_01.do

- NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). (2020). Coral reef conservation program, NOAA official report.

- Oh, H. (2006). 환경경제학 [Environmental economics] (전정판) [Revised edition]. 법문사 [Beobmunsa].

- Park, J., & Cho, D. (2015). Conceptual model of economic evaluation of Korean social crisis according to climate and environmental changes. National Management Research, 10(1), 17-39.

- Park, S. Y., Lee, C. S., Kim, M. S., Jo, I. Y., & Yoo, S. H. (2018). The conservation value of coral communities in Moonseom ecosystem protected area. Journal of the Korean Society of Marine Environment & Safety, 24(1), 101-111. https://doi.org/10.7837/kosomes.2018.24.1.101Article

- Peh, K. S. H., Balmford, A., Bradbury, R. B., Brown, C., Butchart, S. H., Hughes, F. M., & Birch, J. C. (2013). TESSA: A toolkit for rapid assessment of ecosystem services at sites of biodiversity conservation importance. Ecosystem Services, 5, 51-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2013.06.003Article

- Pinvidic, B. (2019). The 3-minute rule: Saying less to get more out of any pitch or presentation. Portfolio/Penguin.

- Polak, O., & Shashar, N. (2013). Economic value of biological attributes of artificial coral reefs. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 70(4), 904-912. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fst014Article

- Scott, F. H., et al. (2022). 99% of coral reefs could disappear if we don’t slash emissions this decade, alarming new study shows. World Economic Forum. Available from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/02/coral-reefs-extinct-global-warming-new-study/

- Shin, S. Y. (2024). The value of Jeju soft corals and directions for its conservation. Paran Ocean Citizen Science Center. Available from https://greenparan.org/17/?idx=18421120&bmode=view

- Thy, H. T. (2021). Design research for coral ecosystem protection [Doctoral dissertation, Seoul National University Graduate School].

- United Nations. (2018). Global indicator framework for the sustainable development goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Statistics Division. Available from https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/Global-Indicator-Framework-after-2024-refinement-English.pdf

- UN General Assembly Economic and Social Council. (2023). Progress toward the sustainable development goals: Toward a rescue plan for people and planet report of the Secretary-General (special edition). General Assembly Seventy-eighth session, Economic and Social Council 2023 session. A/78/80-E/2023/64.

- University of Malaysia Sabah Borneo Marine Research Institute (BMRI). Available from https://ums.edu.my/v5/index.php/en/8-general/2067-ipmb

- WWF Coral Triangle Programme. (2023). Voices from the Coral Triangle: Reflecting on 15 years of Cho, commitment and collective action (p. 56).

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

IGEE

IGEE

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite