Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > IGEE Proc > Volume 1(1); 2024 > Article

-

Article

Effective solution-building to prevent dropouts in Korea: The case of Q&A diary development<sup>†</sup> - Sumin Kim*

-

IGEE Proc 2024;1(1):65-77.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.69841/igee.2024.010

Published online: September 30, 2024

Department of Education, Yonsei University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

- *Corresponding author: Sumin Kim, 99sumini@yonsei.ac.kr

- †This research is supported by the Social Engagement Fund (SEF) 2023.

• Received: July 8, 2024 • Accepted: August 14, 2024

© 2024 by the authors.

Submitted for possible open-access publication under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

- 4,256 Views

- 68 Download

Abstract

- The number of out-of-school youth in South Korea has been increasing recently, leading to a corresponding rise in school dropouts. Moreover, the importance of schools is also diminishing. However, schools are a national system designed to protect adolescents, and the collapse of this system is far from desirable. Despite this crisis, support policies for out-of-school youth remain overly simplistic. Current policies in South Korea regarding out-of-school youth are based on a fragmented understanding of these adolescents, focusing primarily on preventing dropouts. These policies fail to consider the various sociocultural backgrounds and contexts influencing adolescents’ decision to leave school. For example, “dropping out” and “academic discontinuation” are more problematic issues. The ultimate goal of this study is not only to prevent dropouts but also to assist adolescents in making the best decisions on the basis of a deep understanding of their identities. As a first step, a diary was designed to enhance self-understanding by fostering narrative identity formation. A user test was conducted to create a Q&A diary that can assist out-of-school youth, and a literature review was performed to design practical solutions for preventing dropouts. Ultimately, this paper proposes increasing the flexibility of the school system and strengthening self-understanding activities in career education as measures to prevent dropout.

- The recent increase in youth dropping out of school to pursue higher education has become a significant social issue. However, societal perceptions of dropping out have also shifted positively. In the past, dropping out was predominantly viewed negatively, but it was gradually recognized as a student choice. Simultaneously, the importance of formal education and the necessity of school systems are perceived to be declining (Chyul, 2022).

- Is the increase in the number of dropouts not a social problem? It is challenging to conclude so. Schools are systems established by the state to effectively and efficiently manage youth who require protection, providing a space where they can grow through various interactions. The rise in dropout and out-of-school youth has the potential to become a social issue for several reasons. On a small scale, dropping out to focus on college entrance exams can lead to a loss of direction in an individual’s career path. On a larger scale, problems may arise, such as an inability to track at-risk youth, issues related to family problems, and exclusion from social support systems due to a lack of affiliation. Moreover, out-of-school youth are more likely to choose to discontinue their education quickly, making the increasing dropout rates among youth a subject that needs careful consideration. Addressing these related issues is essential for genuinely respecting dropping out as an individual choice.

- Therefore, this paper views dropping out as a social issue that needs to be addressed and explores ways to reduce dropout rates. The initial goal of our research was to improve the social perceptions of out-of-school youth; however, through a literature review and surveys, we discovered more critical issues concerning out-of-school youth. In this process, we identified the increasing dropout rates among youth as rooted in two leading causes: “a lack of self-understanding among youth” and “the limitations of talent development systems due to the rigid school system”. In other words, youth choose to drop out because they fail to find the motivation to continue attending school. Career education must include more profound self-understanding education to motivate adolescents to go to school. Simultaneously, strengthening the specialization of vocational schools such as specialized high schools and vocational high schools, such as arts high schools and sports high schools, and creating a social atmosphere that respects diverse career choices for students are essential. Furthermore, promoting “employment first, further education later” should be encouraged to guarantee various career options for students.

- In particular, it is crucial to remember that schools serve as protective institutions for youth. A notable example of schools functioning as protective social systems is the issue of “young carers.” In 2022, Seodaemun District recognized young carers who care for sick family members as a significant social welfare issue. Owing to their age and lack of social experience, young carers are often unaware of welfare systems. This places their household in welfare blind spots, leading to severe problems such as family suicides, and emerging as a critical social problem. However, young carers have already been identified internationally and are receiving support. Notably, schools often play a crucial role in identifying these young carers. The main problem young carers face is the ‘discontinuation of education due to psychological and economic problems’, and surprisingly, teachers and school staff catch the sign of it. Although various support measures exist for youth, minors face numerous restrictions and difficulties in navigating welfare policies (Heo, 2022). Thus, schools act as protectors who closely observe students and seek appropriate support measures.

- Efforts to reduce dropout rates by reinforcing the school’s role are also the cornerstone of creating a sustainable society. South Korea has experienced declining birth rates in recent years. While the decline in birth rates is a complex issue involving various stakeholders, this paper hypothesizes that one of the causes is the rigid school education system and the resulting standardized career paths. Changing the school system may grant freedom to students and parents and bring about significant societal changes.

- Literature Review

- According to the Korea Legislation Research Institute, out-of-school youth refer to adolescents who have left school. The general perception of out-of-school youth often includes dropouts but also encompasses students who have been expelled or dismissed. However, the reasons for dropping out vary widely and include family circumstances, personal career choices, studying abroad, illness, and criminal activity. The lack of analysis or research on the types of dropouts makes it challenging to provide tailored solutions.

- In this paper, distinguishing between the terms “out-of-school youth” and “dropout” is essential. While these terms may seem synonymous, out-of-school youth refers to all adolescents who have decided to leave school. In contrast, dropout specifically refers to those who have discontinued their studies. Therefore, out-of-school youth include dropouts, and it is crucial to make this distinction to define the research objectives clearly [Table 1] (Korea Law Information Center, 2024).

- The fragmented policies that prevent school dropout stem from a lack of understanding of out-of-school youth and those who discontinued their studies. This study was conducted to clarify the essential problem of policymaking. Through literature reviews, surveys, and interviews to identify the issues faced by out-of-school youth, this research identified the issues faced by out-of-school youth, expanded their definition, and categorized surrounding issues [Table 2] (Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, 2022).

- There are four main problems related to out-of-school youth. The first is the negative perceptions of these individuals (Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, 2022). Although the perception of dropping out is gradually improving and the term out-of-school youth is becoming more common, many older generations still view them as dropouts or misfits. The second issue is the difficulty of tracking out-of-school youth due to the lack of affiliation with any institution (Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, 2021). Many out-of-school youth who engage in delinquent behavior are challenging to track and are often neglected until they commit a crime. This highlights the critical role of schools in youth protection and the urgent need for a system to track and protect out-of-school youth. The third issue is that many adolescents who drop out without clear goals or career paths experience lethargy (Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, 2021). This is often true for students who drop out because they find school uninteresting, as they lack specific aspirations and struggle with career exploration and decision-making. The fourth issue is that some youth drop out because their primary caregivers, usually parents, face difficulties that prevent them from continuing their education (Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, 2021). These youths often enter the workforce after dropping out, particularly those who must care for sick parents as young caregivers. Since high school dropouts have few job opportunities, policies are needed to help dropouts return to their studies.

- By addressing these issues, we can develop a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges faced by out-of-school youth and create more effective policies and systems to support them. Schools have implemented the “Academic Discontinuation Reflection System” policy to prevent dropouts. This system encourages students who apply for dropout to reconsider their decision, but its effectiveness is limited by its nonmandatory nature, making it insufficient as a dropout prevention policy (Kim, 2022). Additionally, although the government has provided ongoing support, such as learning grants for out-of-school youth, this support remains fragmented. Moreover, the situation is unstable, with sudden reductions in support amounts depending on stakeholder interests. Most importantly, the overall system for tracking and protecting out-of-school youth remains inadequate. The government announced in 2023 that it would create tracking statistics to develop a system for monitoring out-of-school youth, but specific progress has yet to be confirmed [Table 3] (National Youth Policy Institute, 2023).

- According to statistics, the number of out-of-school youth in Korea was estimated to be approximately 168,000 (167,925) in 2022. The number of out-of-school youth has steadily declined since 2013 but has sharply decreased in 2021 before increasing by approximately 20,000 in 2022. This estimate indicates the number of out-of-school youth between the ages of 6 and 17 each year. We can infer changes in this number by analyzing the cross-sectional state of school dropouts. Dropouts steadily decreased from 2013--2015, increased from 2016--2019, and sharply declined in 2020. However, the number of dropouts increased in 2021 compared with the previous year. The dropout rate also increased by 0.2 percentage points to 0.8% in 2021, returning to a level similar to that before the sharp decline in 2020 [Figure 1 & 2] (Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, 2022).

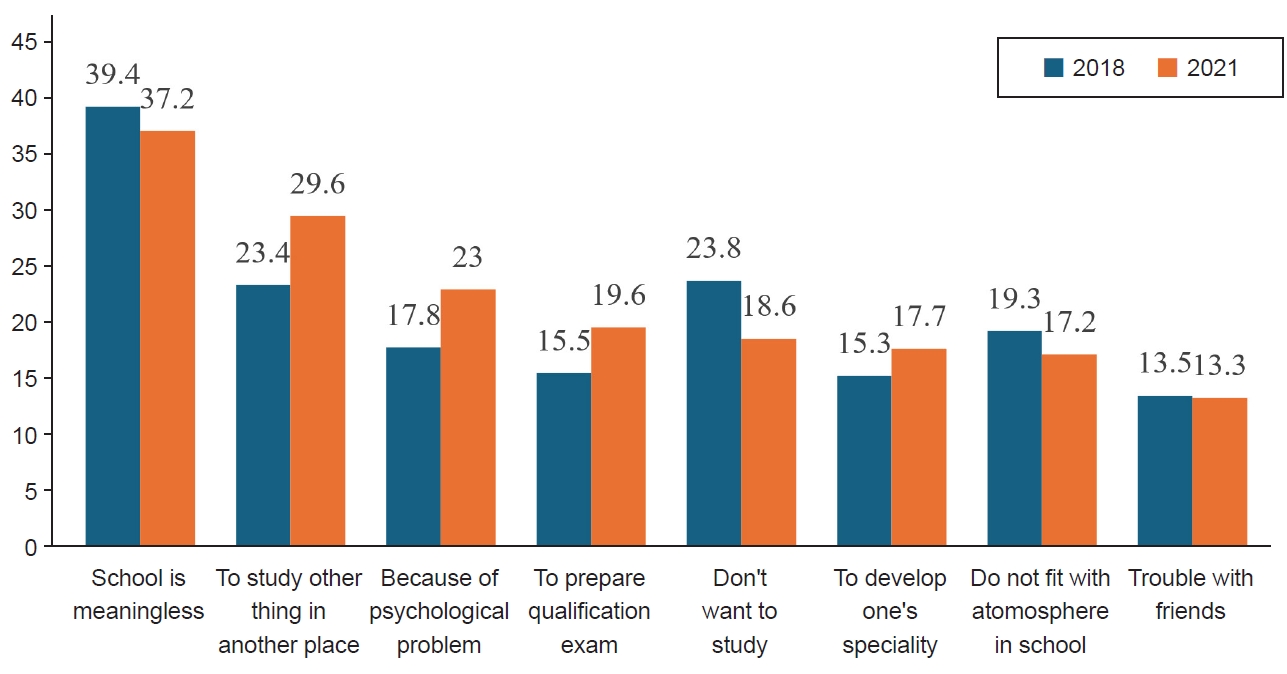

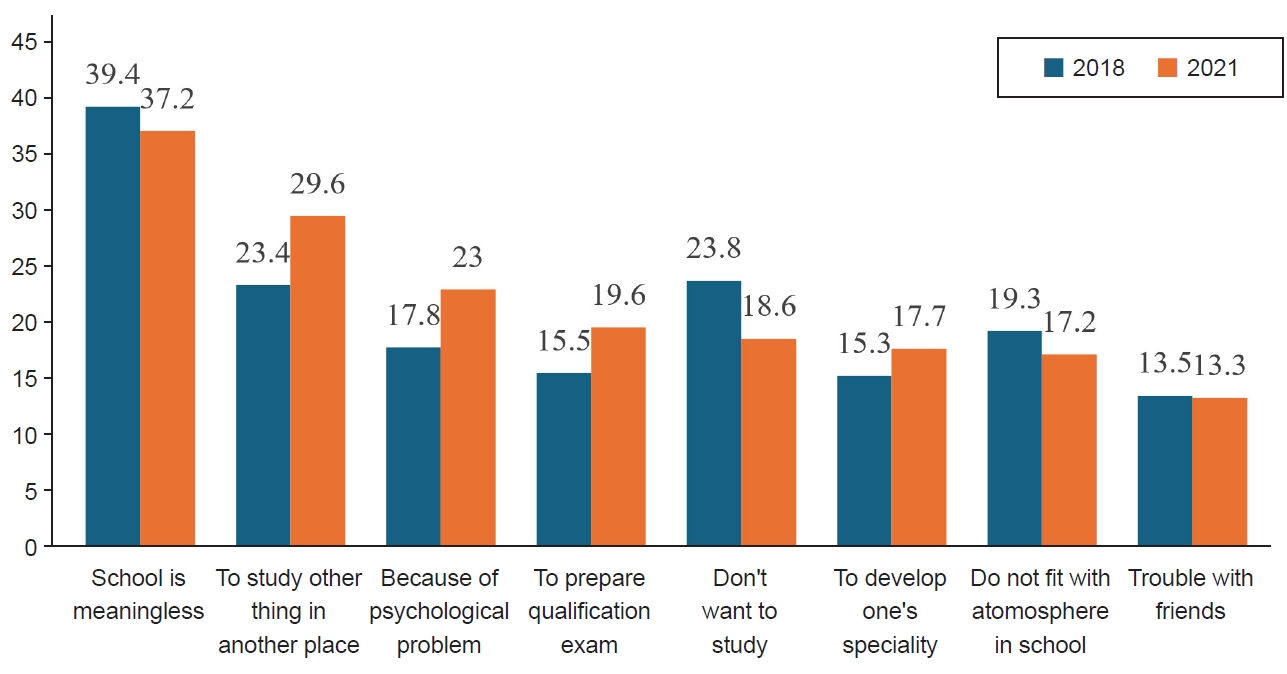

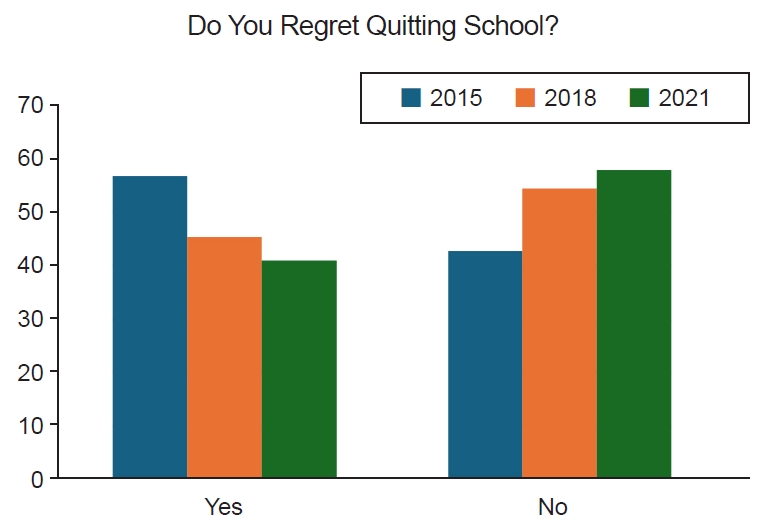

- Analyzing the reasons for dropping out reveals a dual pattern. The proportion of youth who dropped out “to learn something they wanted elsewhere” increased by 6.2 percentage points to 29.6% compared with that in 2018, and the proportion of those who dropped out “to develop a specific skill” also increased. Additionally, the number of youth who responded “no” when asked if they regretted dropping out steadily increased. Moreover, emotional and financial support from parents for dropping out has increased, whereas abuse and neglect have decreased. This suggests that more young people are making confident career choices at the point of dropping out.

- However, a significant proportion of youth also dropped out for reasons such as “feeling that school was meaningless”, “psychological or mental issues”, “disliking studying”, “inability to adapt to the school environment”, or “problems with school friends”, with each reason accounting for at least 10% and up to 37%. Over 40% of the youth reported regretting their decision to drop out. Many respondents stated that they would not have chosen to drop out if there had been appropriate career exploration support policies and interest from teachers. Only 45.6% of the youth had decided on a career path before dropping out, and 16.7% took more than two years, indicating that many adolescents are dropping out without clear goals [Table 4-6] (Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, 2022).

- The following table presents the survey results on support measures that could have prevented students from dropping out. The main reasons for dropping out were the lack of classes that could utilize their talents and the absence of support services related to what they wanted to learn. This issue can be attributed to Korean schools' overly standardized, test-focused culture. Therefore, there is a need to expand support for specialized high schools, such as arts and sports schools, and vocational high schools, such as Meister High School. This approach suits students who prefer nonacademic career paths and can function as a social safety net for those who prioritize employment due to their economic background. Therefore, the expansion of specialized and vocational high schools should be pursued alongside the development of higher education pathways such as “posteducation employment.”

- Hong and Kim (2023) made a summary of the mindset of out-of-school youth. Hong and Hwang (2018) identified the psychological characteristics of out-of-school youth as follows. First, they tend to be anxious or unstable, leading to lower levels of happiness. Second, they have significantly shorter sleep times than do general adolescents. Third, they have a negative view of themselves and their situation. Fourth, they quickly feel defeated and experience shyness and loneliness. Fifth, they lack communication skills and cannot share their problems with others. These psychological characteristics of out-of-school youth include high levels of anxiety, depression, loneliness, shyness, and low self-resilience due to their anxious personalities and difficulties in relationship experiences. Hong and Kim (2023) reported that out-of-school youth are more likely to discontinue their studies because of unstable psychological states and family environments, which negatively impact their career choices. (Hong & Kim, 2023)

- To improve adolescents’ self-concept, the self-understanding component of career education must be strengthened, and the school system should be made more flexible to allow adolescents to explore various careers within the school system. In Korea, the term ‘career’ is often used interchangeably with ‘occupation’, but a career encompasses not just a job but also an entire life journey.

- Self-concept is a crucial factor in career planning. Self-understanding, including self-esteem, self-role, and self-concept, is essential for career development. A career encompasses a broad scope beyond just an occupation, and effective career choices require specific knowledge of oneself and the world of work, as well as timely exploration and decision-making.

- However, Korea’s career education tends to focus more on understanding the world of work rather than self-understanding. From elementary school, career education often involves listening to lectures about specific occupations or experiencing the work of certain job categories, which have become representative learning activities in career education. Of course, understanding the world of work plays a crucial role in helping students choose jobs that match their interests and aptitudes. Programs such as the Free Semester System actively promote career exploration. However, providing comprehensive education on the concepts and types of occupations and their purposes is essential rather than just ending with job experiences.

- Korea’s career education tends to be overly focused on vocational education. Therefore, we emphasize the importance of self-understanding through the formation of a narrative identity. In career and vocational education classes, self-understanding is often inadequately addressed. The first unit of the <Career and Vocational> course typically addresses self-understanding, and excerpts from the textbook emphasize the importance of understanding one’s characteristics in career education [Table 7-8](National Curriculum Information Center, 2022).

1. Introduction

- Materials

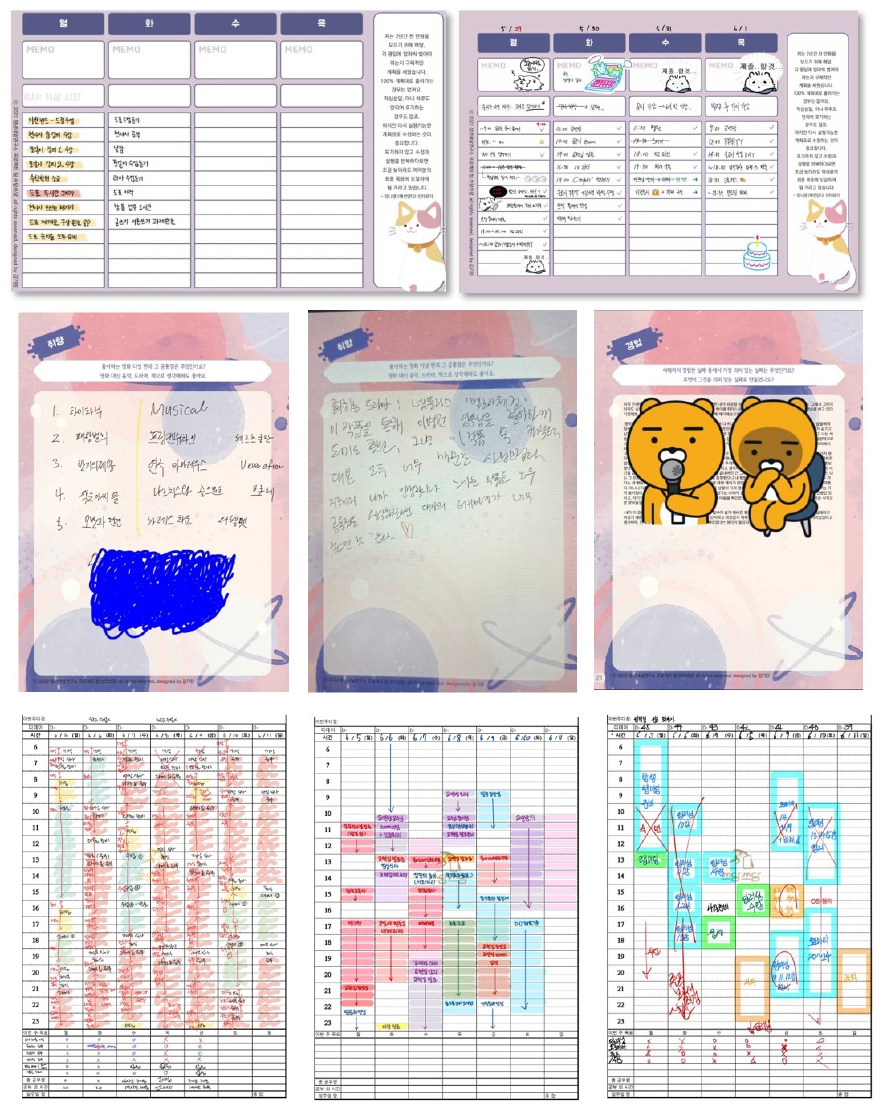

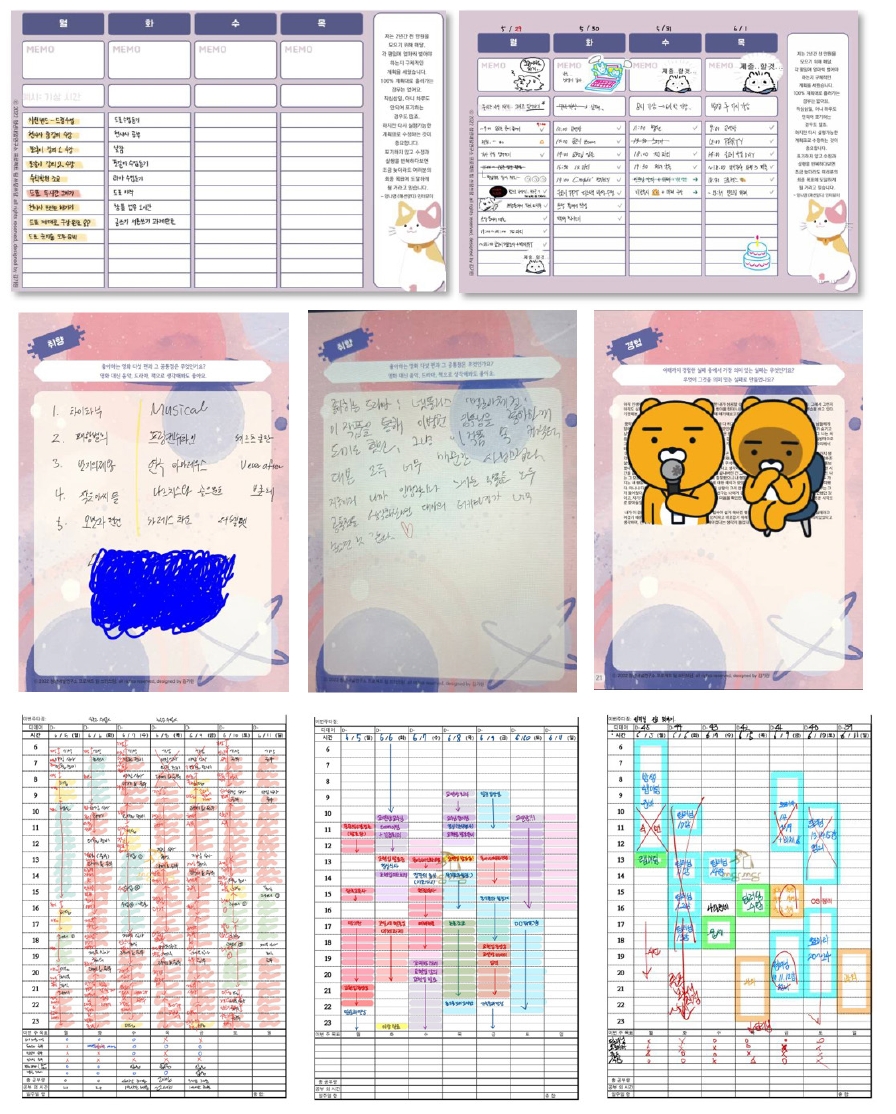

- We developed a narrative identity formation planner to promote career education on the basis of self-understanding. In 2021, we completed the production and distribution of the first version of the <Write Light(쓰담플래너)> diary. This planner focuses on identity formation by answering questions in four categories: experiences, preferences, relationships, and self. It also includes a monthly planner independent of school schedules, interviews, and information for out-of-school youth.

- In 2023, a user test was conducted to develop a new <Write Light> version. The purpose of this test was to verify the usability of the planner, expand its target audience from out-of-school youth to general youth, and validate and supplement the necessary content. The user test was conducted over two weeks, from May 28 to June 15, 2023, with 13 university students in their early twenties who participated to improve their daily lives. During the first week, the participants used the existing narrative planner and evaluated their satisfaction and areas for improvement. In the second week, they tested a new feature, the time tracker. The detailed experimental schedule is as follows.

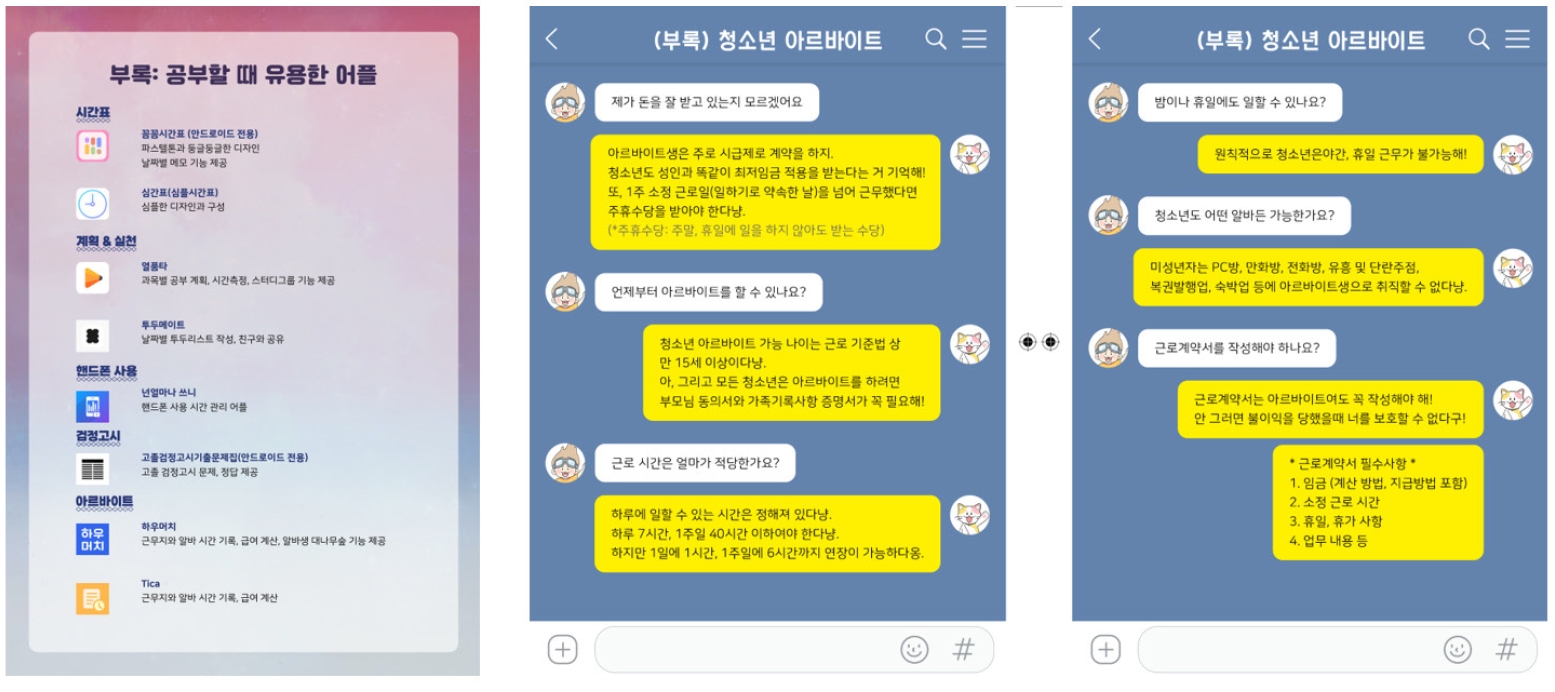

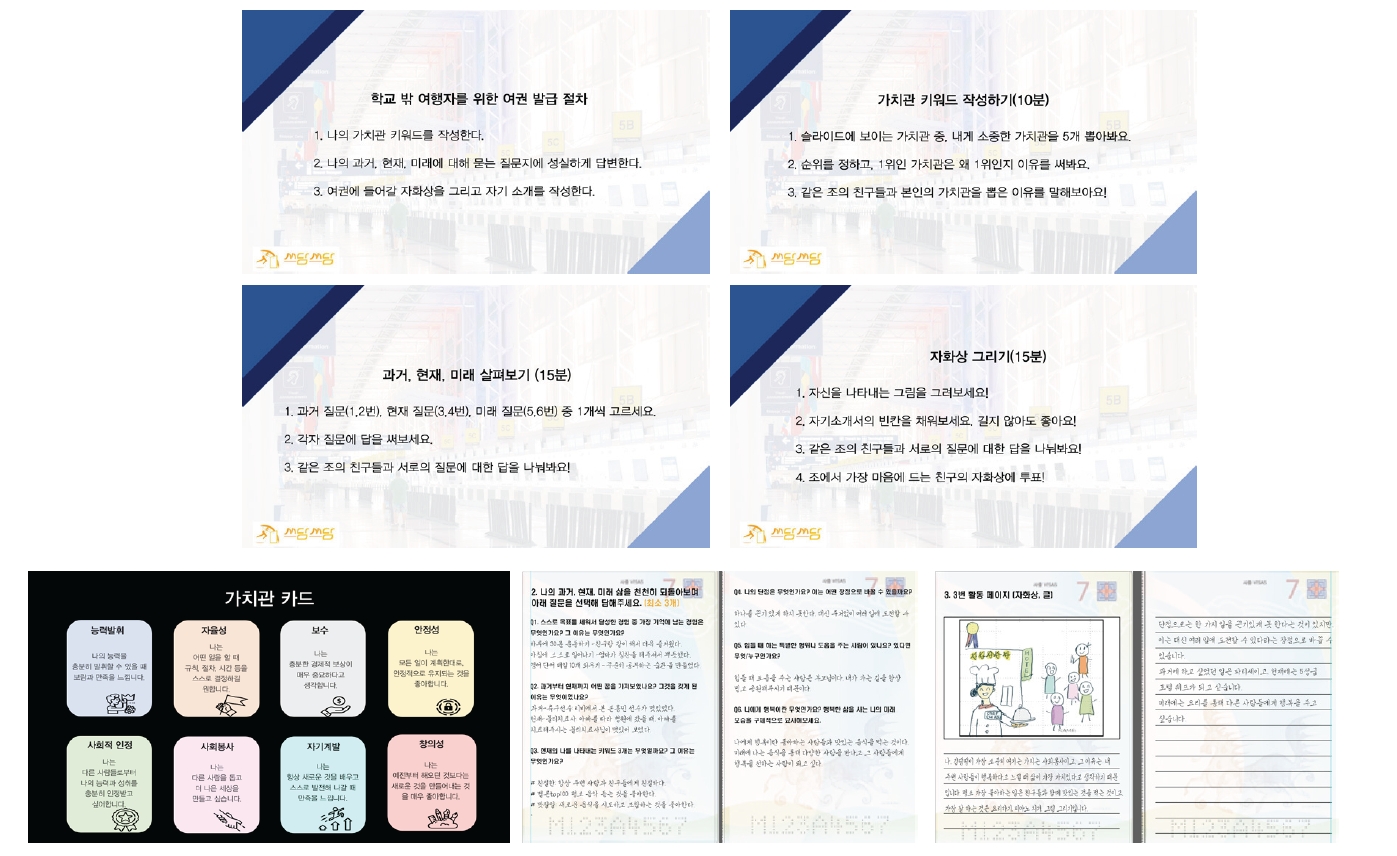

- We collected feedback from actual users to identify improvements for <Write Light>. Various types of feedback were received on the composition and layout of the questions, design, and appendices, and the planner was improved on the basis of this feedback. The monthly layout was expanded from one month to three months, the time tracker was replaced with a self-directed learning column, and all youth-related information was updated with the latest content. Additionally, worksheets have been developed that are easy to use in career education classes and can be easily shared with others [Figure 3].

- Methods

- Our research chose two tracks, a literature review and a user test, to develop the diary we produced. The user test was designed to use a sample diary and provide a review. The participants obtained two samples from the diary and used them in real life. Sample 1 is the existing diary, the one we designed last year, and sample 2 is the new content of our diary, the time tracker. Sample 1 is offered in Week 1, and Sample 2 is provided in Week 2. The details are as follows [Table 9]:

- Participants: We gathered 14 university students for the user test, 13 of whom had finished the entire test course.

- The reasons for participating in the test varied, but the most common reason was “hope to try time management” (85.7%). “To make an efficient study plan (64.3%)” was the highest motivation for participants. Rarely, “interested in your project (28.6%)”, “to overcome depression (21.4%)”, and “not satisfied in an ordinary diary/planner (14.3%)” followed.

- The participants had to upload their everyday records of diaries and attend online orientation and face-to-face interviews. We used an anonymous group chat room in KakaoTalk to collect everyday records. All the participants were included in a group chat room, so their records were shared with us and with the others.

- When the participants finished the whole course of the experiment, they received a gift card worth 30,000 won for the reward. The fundamental information about the participants is as follows [Table 10-11]:

- Measures: We used objective questions with a Likert scale to measure participants’ satisfaction approximately. Subjective questions are inserted to determine accurate reasons for their answers.

- Analysis: This is the result of our user test for our planner [Figure 4].

- The survey questions were composed of self-reports and subjective types. A Likert scale was used to record the self-reported answers:

2. Materials and methods

1) Summary of the Week 1 Survey

2) Summary of the Week 2 Survey

3) Summary of Subjective Questions

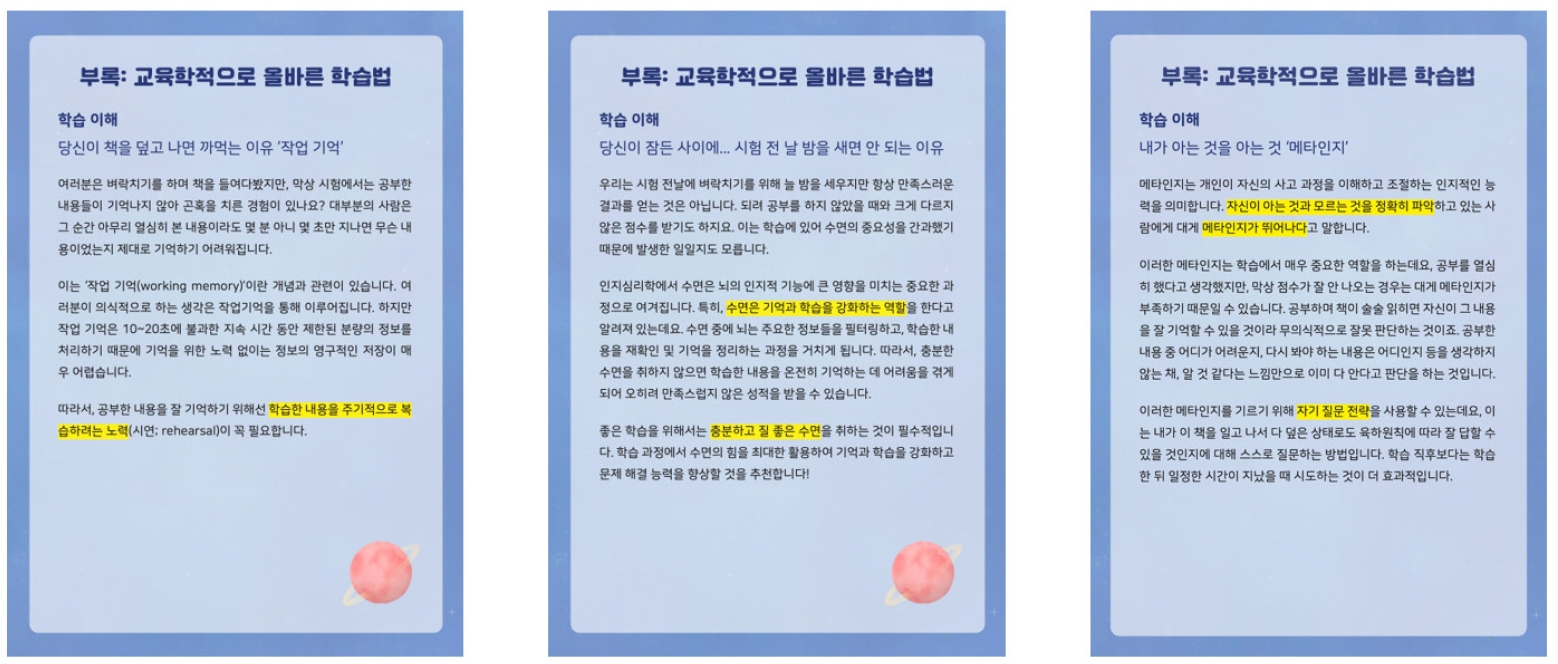

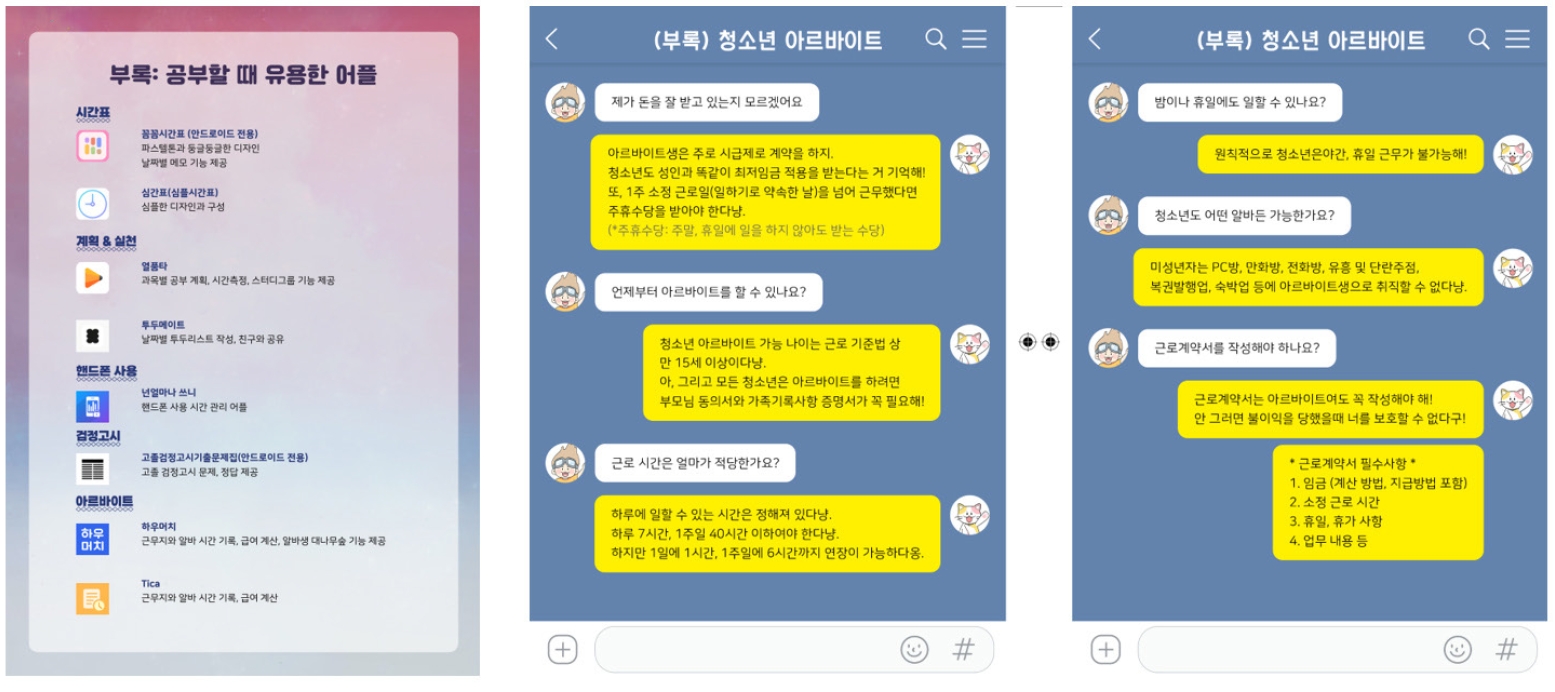

- On the basis of the results of the user test, three significant changes were applied to the diary: (1) the usage period of the diary was extended from one month to three months, (2) articles on learning science and routines to support self-directed learning were added [Figure 5], and (3) updated information on out-of-school youth was included. Additionally, improvements such as character design enhancements [Figure 6 & 7] have been made

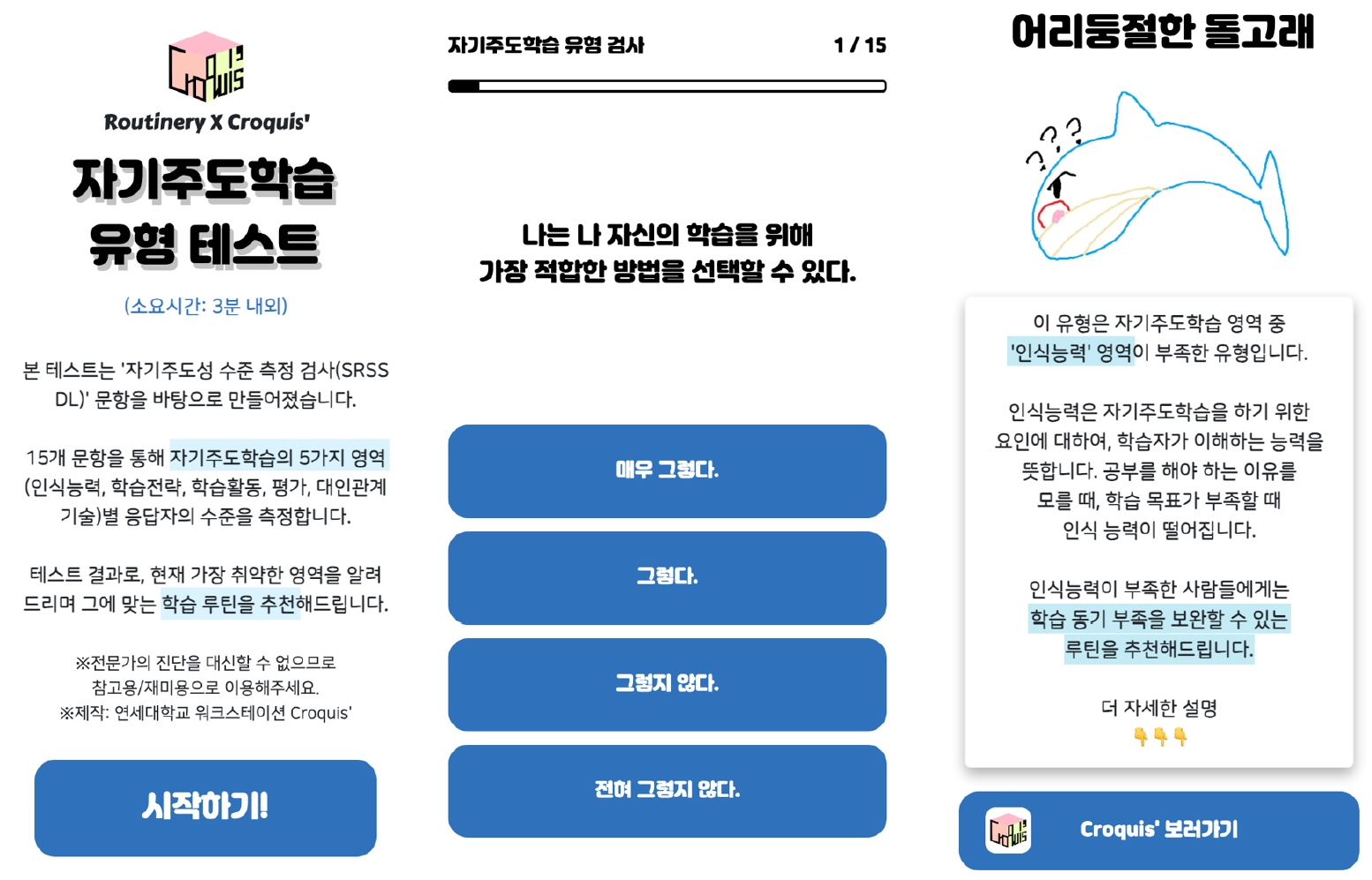

- Furthermore, a simple self-report test was developed to diagnose strengths and weaknesses to increase interest in learning and strengthen self-directed learning abilities [Figure 8]. This test was designed to motivate adolescents by providing intriguing results and encouraging them to take action in their studies. However, it may not be highly valid from an educational perspective. The test can be accessed via this link (https://sachungi-yonsei-27279.waveon.me).

- Below is an example of self-understanding enhancement activity sheets designed for use in career education. These activities were created on the basis of the <Write Light> diary and consisted of three exercises: selecting essential values in life; answering questions about past, present, and future life; and envisioning one’s future self. Using career education time to foster students’ sense of identity can help identify and address the concerns of students considering dropping out due to psychological burdens or teacher indifference, provide a support channel and help prevent dropout.

3. Results

- The author suggested that to address issues related to out-of-school youth, expanding the perceptions of these youth from simply being ‘dropouts’ to recognizing them as ‘youths who are not affiliated with school for various reasons’ is essential. Therefore, developing and implementing diverse support policies to address these underlying causes is necessary. It is critical to prevent student dropout by increasing the flexibility of school formats and systems and enhancing career education.

- The table below presents statistics from a survey on what support might have prevented students from dropping out of school. The primary reasons identified were the lack of classes that could harness their talents and the absence of support services that connected them with what they wanted to learn. These issues can be attributed to South Korean schools’ highly standardized, exam-oriented culture. Therefore, there is a need to expand support for specialized high schools, such as arts and sports schools, and vocational high schools, such as Meister schools, which offer professional and technical education. This approach caters to students with nonacademic career paths and serves as a social safety net for those prioritizing employment due to economic background. Consequently, expanding specialized and vocational high schools and developing postsecondary education pathways such as ‘employment after further education’ should be pursued simultaneously.

- Compared with that in other countries, career education in South Korea is highly structured. As of April 2016, 96.6% of the schools had career counselors, with a goal of 100% placement in all schools. Most middle and high schools establish career education plans and budgets, and students engage in various career exploration and experiential activities through ‘career activities’ in creative experience programs and elective subjects such as ‘Career and Occupation’. The national curriculum guidelines have increasingly emphasized career education, with the 2015--2022 revised curriculum guiding schools to organize and operate career-centered education programs.

- Despite the systematic framework, reality shows a lack of infrastructure to invigorate career education. Career counselors are assigned to schools, but a single counselor often has to manage the entire student body, leading to an overwhelming workload. Schools without career counselors struggle to offer career-related classes. Furthermore, career education becomes nearly impossible after middle school due to the intense focus on college entrance exams, making it difficult to conduct meaningful career-related activities during designated times. The lack of collaboration between schools and related institutions results in insufficient instructional materials beyond the ‘Career and Occupation’ textbook. Addressing these issues could lead to significant improvements in the effectiveness of career education within schools.

- Career education should shift its focus from merely introducing and experiencing various occupations to ‘identity exploration activities’ that enhance students’ self-understanding and help them establish life values and directions. Career education is not just about choosing a job but rather about defining the overall direction of one’s life, making this shift critical.

- Below is an example of an activity sheet designed for use in schools. Using career education time to foster students’ sense of identity can help identify and address the concerns of students considering dropping out due to psychological burdens or teacher indifference, providing a channel for support and preventing dropout.

- Ultimately, reducing dropout and academic discontinuation rates is a way to protect youth. It is generally beneficial for adolescents to be affiliated with schools. Schools are not just places for academic learning but also environments where students form diverse human relationships, learn social norms and etiquette, achieve socialization, and act as protective social systems for youth. The crucial role of schools as protective institutions for youth is particularly noteworthy.

- Out-of-school youth often cite a lack of belonging and the resulting forms of alienation as significant challenges. This can manifest as personal anxiety or a sense of social exclusion. Moreover, the eligibility requirements for many youth competitions in South Korea are often restricted to students. Many support policies are publicized and applied through schools, highlighting the overwhelming importance of schools in youth protection.

- A notable example of schools as protective social systems is the case of ‘young carers.’ In 2022, Seodaemun-gu recognized young carers caring for ill family members as a significant social welfare issue. These youths are often unaware of welfare systems due to their circumstances, placing them in welfare blind spots and leading to recurring suicides among young carers, which poses a significant social problem (Shin, 2022).

- However, internationally, young carers are already identified and supported, with schools often being the first point of detection. The primary issue faced by young carers is the ‘interruption of education due to psychological and economic problems,’ which is paradoxically most likely to be noticed by teachers and school staff. Despite the availability of various support measures for youth, minors face numerous restrictions and difficulties in navigating welfare policies. Hence, teachers serve as protectors who closely observe students and find appropriate support measures (Heo, 2022).

- Modern schools extend beyond educational institutions to protect students, making it beneficial for most youth to attend school. Out-of-school youth and dropouts lack social mechanisms to manage them, making it difficult for them to access the welfare benefits provided by the state (Ministry of Education, 2023). Therefore, it is advantageous for youth to remain in school as much as possible. The state must quickly establish other social networks and preventive measures for those who choose or cannot attend school. This study aims to be the starting point for such efforts.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Table 1.Legal definition of out-of-school youth in South Korea

Table 2.Difficulties after Quitting School

Table 3.Current Assumed Scale of Out-of-school Youth

Table 4.Factors that Are Needed in School

Table 5.Career Plan after Quitting

|

By year |

By sex |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2018 | 2021 | Male | Female |

| 25.0 | 35.0 | 35.7 | 41.6 | 29.8 |

Table 6.The time at which the career decision was made

| Before quitting school | After 6 months | 6 months~12 months | A year~ a year and a half | A year and a half~2 years | More than 2 years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 45.6 | 16.2 | 7.7 | 8.7 | 3.9 | 16.7 |

Table 7.The Character of Career and Vocational Courses

Table 8.Evaluation Directions for Career and Vocational Education

Table 9.Timetable of the User Test

Table 11.Age Range of the Participants

| Age | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 28 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Number of Participants | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Total | 12 | Average | 23(22.91) | ||||||

- Chyul Young, J., Lee, Y. G., Lee, S. Y., Kim, D. J., Kim, G. M., Yi, J. G., & Kim, D. H. (2022). National career education policy trends in Korea. The Journal of Career Education Research, 35(1), 81-109. https://doi.org/10.32341/JCER.2022.3.35.1.81Article

- Heo, M. (2022). Support systems for young carers abroad and implications: Tasks for supporting youth caring for family members and preventing isolation (Report No. 242). NARS Current Issues and Analysis. https://www.nars.go.kr/report/view.do?categoryId=&cmsCode=CM0043&searchType=NM&searchKeyword=%ED%97%88%EB%AF%BC&brdSeq=38162

- Hong, S., & Kim, C. (2023). A case study on out-of-school youth withdrawal and career choice. A Case Study on Out-Of-School Youth Withdrawal and Career Choice, 23(15), 713-726. https://scholar.kyobobook.co.kr/article/detail/4010047560689Article

- Korea Law Information Center. (2024, September 27). Legal definition of out-of-school youth in South Korea. https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/lsInfoP.do?lsId=012054&ancYnChk=0#0000

- Ministry of Education. (2023). Strategies for enhancing career education (2023-2027) [Press release]. https://www.moe.go.kr/sn3hcv/doc.html?fn=3ae54767a4f281f04942bd9c66b0aa10&rs=/upload/synap/202307/

- Ministry of Gender Equality and Family. (2021). 2021 survey on out-of-school youth (Report No. 11-1383000-001086-01). https://www.mogef.go.kr/io/lib/lib_v100.do?id=28808

- Ministry of Gender Equality and Family. (2022). 2021 survey on out-of-school youth [Press release]. https://www.data.go.kr/data/15123387/fileData.do

- National Curriculum Information Center. (2022). 2022 middle school elective curriculum (Report No. 2022-33). https://ncic.re.kr/mobile.dwn.ogf.originalFileTypeDownload.do

- National Youth Policy Institute. (2023). Estimation of the number of out-of-school youth in 2022. https://www.ypec.re.kr/board/view?menuId=MENU00312&linkId=1981

- Out-of-School Youth Support Division, Office of Youth and Family Policy. (2022). 2021 survey results and support measures for out-of-school youth. https://www.mogef.go.kr/nw/rpd/nw_rpd_s001d.do?mid=news405&bbtSn=708556

- Shin, S. (2022, October 4). Seodaemun District, Seoul, implements nation’s first comprehensive plan to support young carers. NEWSRO. https://www.newsro.kr/article243/206214/

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

IGEE

IGEE

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite