Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > IGEE Proc > Volume 1(1); 2024 > Article

-

Article

Empirical Study on the Usage and Promotion of Sustainable Feminine Hygiene Products<sup>†</sup> - Chaeni Park1*, Eunsol So2

-

IGEE Proc 2024;1(1):78-89.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.69841/igee.2024.011

Published online: September 30, 2024

1Department of Psychology & Industrial Engineering, Yonsei University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

2Department of Psychology, Yonsei University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

-

*Corresponding author: Chaeni Park, goodchaeni@yonsei.ac.kr

†This research is supported by the Social Engagement Fund (SEF) 2023.

• Received: July 1, 2024 • Accepted: August 14, 2024

© 2024 by the authors.

Submitted for possible open-access publication under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

- 3,416 Views

- 28 Download

Abstract

- Compared with disposable equivalents, sustainable feminine hygiene products are promising for reducing pollution and could lead to the amelioration of the menstrual cycle, with overall health benefits for women. Through empirical research and online promotion, this study aimed to examine the efficiency and comfort of reusable menstrual products and address the SDGs that target climate change and a healthy lifestyle for global citizens. The data were collected by distributing products to 26 women aged 18--28 years and collecting responses through curated questionnaires before, during and after usage for 2 months. Our main findings showed that women reported a better sensory experience with reusable products with improved comfort and positive changes in their perception, which led them to continue using the pads in the future. Thus, we can conclude that sustainable feminine hygiene products may garner positive reviews from their users; with adequate promotion and support, we can work toward the goal of prospective benefits both for women and the environment.

- Women have been menstruating for 40--50 years. During this period, women are required to use disposable or multiple-use menstrual products. In 2017, a study reported that disposable sanitary pads may contain toxic chemicals. In 2020, women’s anxiety intensified when the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety announced that 98.4% of disposable sanitary pads may contain carcinogens.

- The dangers of disposable sanitary pads extend beyond individual health risks. It is also a pollution factor that has a harmful effect on the environment. On average, a woman generates approximately 1 ton of waste from her menstrual products over her lifetime. Currently, 90% of the disposable sanitary pads on the market are not naturally decomposed upon disposal. As a result, the sanitary pads used are incinerated, and toxic chemicals are released into the atmosphere.

- Therefore, for women's physical health and environment, it is necessary to collect and distribute information so that women can use sustainable menstrual products.

- We attempt to reconsider women's perceptions of menstrual products to cope with women's health and climate change. The effects of disposable/multiple-use menstrual products on women's bodies and how they differ in terms of the environment were compared through evidence-based literature. In addition, we sought ways to encourage more women to use sustainable menstrual products. In particular, the discourse surrounding women's menstruation in Korean society currently tends to be taboo. Each woman has a different perspective on menstruation and sanitary pads depending on her culture and economic status. In other words, menstruation appears to be a universal physical experience for women, but its interpretation and understanding differ depending on the time, place, religion, and socioeconomic situation where women are located, and the way menstruation is handled varies (Vostral, 2008). To address these limitations, we tried to raise awareness of the importance of the sustainability of hygiene products for women and to answer women's questions through communication.

- Our research is related to SDGs 3 of good health and well-being and goal 13 of ‘climate action’. In the initial plan, we wanted to develop an application. The subject of our study was women of childbearing age around the age of 20. We conceived an application that included a newsletter based on accurate information and communication services between users. However, while conducting the research, we learned that the target woman wanted to obtain knowledge about menstrual products more simply than the application we originally planned. Accordingly, we concluded that providing information in the form of a short video on an Instagram account is more suitable for the demand of women around the age of 20. In addition, it was judged that women who were not interested in multiple use menstrual products would be naturally exposed to multiple use menstrual products through Instagram and improved accessibility. On the basis of the opinions received in the study, we made a video containing how to easily wash cotton sanitary pads and a video introducing products that help manage them. A social media account was created and launched, which helped to distribute information for research purposes.

1. Introduction

- Materials

- The scope of the study was multifaceted in terms of companies and consumers, focusing on major stakeholders in the use of menstrual products. 26 women that were actively experiencing their menstrual cycle were recruited to distribute cotton sanitary pads, and the effects on individuals such as the feeling of use and future availability were reported through three online questionnaires before, during and after their menstruation. Reusable cotton menstruation pad kits with multiple items were purchased beforehand, and distributed to each participant in person. In addition, The Brand Hannah (한나패드), which sells multiuse menstrual products as a product, was interviewed to determine major customers, market prospects, and environmental effects.

- A literature review was conducted prior to the empirical study to accumulate background information on the status quo of menstrual product use. To determine whether the use of multiple menstrual products can be an alternative to disposable menstrual products, papers and news articles dealing with social problems surrounding menstrual products were analyzed. Published and relevant works have examined the scope of consumer experience, the proportion and frequency of usage for each product and how feminine hygiene products directly contribute to waste generation in the environment. The research focused on Korean women and schoolgirls, and these data were used to inform the methodology and surveys for the subsequent study.

- Through empirical research, the perceptions and use of menstrual products by women around the age of 23 were investigated. The empirical study was conducted via the participant questionnaire method and targeted women around the age of 23 who had no experience using cotton sanitary pads [Figure 1]. Through online social services such as Everytime, Instagram account, and the Yonsei University Department Kakao Talk group chat room, 26 participants were recruited, and 24 participants conducted the study by responding to all three surveys. The participants who completed the survey study were given a Naver Pay gift certificate of 50,000 won each [Figure 2]. Personal information such as contact information provided by participants was discarded after being used only for research and case payments, and this information was announced in advance. The participants who participated in the study were able to ask the researcher questions anonymously at any time. The anonymity of all participants was guaranteed, and if the participants wished to stop the survey, it was announced that it could be stopped without any disadvantages. For 23 participants, with the exception of 3 inevitable participants, cotton sanitary pads were distributed face-to-face at Yonsei University's Sinchon Campus. In this process, the participants were anonymously provided with sanitary pads.

- The questionnaire included both structured multiple-choice questions and unstructured descriptive questions. Before the participants were given cotton sanitary pads, the first questionnaire was distributed, which included questions to determine their interest in their health (a week’s exercise, in which time exercise refers to the intensity of sweating), questions to determine what they are most interested in when purchasing menstrual products, questions to determine their loyalty to the brand or product, and questions to determine if they consider the environment.

- "Participants received cotton sanitary pads either face-to-face or by courier and were given 2 months to use them freely. Touch, wear, replacement frequency, laundry burden, odor, clothing restrictions, activity restrictions, and menstrual pain effects of cotton sanitary pads were compared to disposable sanitary pads, using a 3-point or 5-point scale.

- The questionnaire included both structured multiple-choice questions and unstructured descriptive questions. Before the participants were given cotton sanitary pads, the first questionnaire was distributed, which included questions to determine their interest in their health (a week’s exercise, in which time exercise refers to the intensity of sweating), questions to determine what they are most interested in when purchasing menstrual products, questions to determine their loyalty to the brand or product, and questions to determine if they consider the environment.

- "Participants received cotton sanitary pads either face-to-face or by courier and were given 2 months to use them freely. Touch, wear, replacement frequency, laundry burden, odor, clothing restrictions, activity restrictions, and menstrual pain effects of cotton sanitary pads were compared to disposable sanitary pads, using a 3-point or 5-point scale.

- Finally, after menstruation ended, the participants were asked to complete the third questionnaire. Compared with before using cotton sanitary pads, questions such as whether there is a change in perception after use, the accessibility and price of multiple-use menstrual products are appropriate, and what measures are available to expand the use of multiple-use menstrual products?

- A Korean mainstream menstrual product brand, Brand Hannah, consented to an interview to collect information on the environmental protection effects of consumers’ most preferred multiple-use menstrual products and multiple-use menstrual products. We explored ways to encourage consumers with sustainable menstrual products.

- Instagram was opened to recruit participants in case study questionnaire monitoring and social impact using research results (ID: @invisible.yonsei). This aimed to establish a platform wherein we could communicate essential information about the maintenance of reusable products, eliminating stereotypes and ensuring that queries were answered. We accumulated the qualitative and quantitative data gathered from the participants and launched a social media account. These posts were shared in the form of card news as static images and posters, as well as edited videos with clips and text that aided in understanding the information visually.

2. Materials and methods

1) Literature Review

2) Monitoring the Experience of Multi-Use Menstrual Products through Survey

3) Interview with the reusable pad company The Brand Hannah

4) Creating a social media account and releasing information posts

- 1) Literature Review

- Menstrual hygiene is defined as ‘the practice of managing menstruation safely and with dignity’ (House, 2015). In Korea, there are groups who struggle with access to sanitary pads and others who seek alternatives to disposable products. While disposable sanitary pads cause anxiety and environmental concerns for many women, there is a lack of domestic resources providing information about menstrual products. In Korea, where menstruation is often not openly discussed due to traditional social norms, menstrual hygiene issues have been largely neglected. The movement of menstrual hygiene in other countries has been investigated in the literature.

- Menstrual hygiene is a practice for improving physical safety and daily life in countries with poor hygiene infrastructure and for the well-being and ethical consumption of rich countries. In other words, development organizations, private organizations, and companies promote mutual benefits through social contributions to women in various communities.

- Kenya’s social enterprise ZanaAFRICA distributes disposable sanitary pads to schools through 21 local partner organizations and guides girls in menstrual hygiene education by conducting training programs with partner organizations.

- Sustainable health enterprises (SHEs), Rwandan social enterprises, allow local women to manufacture sanitary pads using local resources. By recycling banana fiber, we have developed the “goPad,” a local brand of sanitary pads, which is inexpensive, safe, and biodegradable and provides school menstrual hygiene education for both girls and boys (Noh, 2016).

- In addition to economically poor countries, countries are implementing various policies to address menstrual poverty. Since 2020, England has provided free menstrual products to students at all state schools and approximately 20 educational institutions. It includes multiple types of menstrual products, such as menstrual cups and cotton sanitary pads. In addition, the so-called 'tampon tax', which classified menstrual products as luxury goods and imposed a tax of at least 5%, was abolished across the UK in 2021.

- Spain’s Catalan governor, Pere Aragonès, announced in September 2021 that he would provide menstrual products to vulnerable groups of women. In particular, he emphasized that he would prioritize access to reusable products.

- In August 2022, Scotland announced the Menstrual Supplies Act, which provides free menstrual products to all women in need by public institutions. It is the world's first measure to provide free menstrual products by expanding the scope of support from existing public school students to all women.

- South Korea's menstrual poverty problem is a blind spot. According to an online survey of 1,234 female adolescents nationwide conducted by the Seoul Youth and Menstrual Products Universal Payment Campaign Headquarters in May 2021, 967 (74.7%) said, “I have hesitated to buy menstrual products because of the high cost.” The Korean government revised the Youth Welfare Support Act in 2021 and stipulated in Article 5(3) that “the state and local governments support female adolescents when they apply for menstrual products for the healthy growth of female adolescents,” and the Seoul Metropolitan Council revised the ordinance in December 2019 to specify “universal payment of menstrual products,” but it has not yet secured a budget (Son, 2023).

- In 1980, 813 cases of toxic shock syndrome and 38 deaths were reported among American women who used P&G’s tampon Rely, making the harmfulness of disposable menstrual products publicized. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires a warning about tampon-induced toxic syndrome to be displayed on the package. Disposable sanitary napkins contain harmful ingredients such as dioxin, and disposable sanitary napkins contain polyethylene, an environmental hormone that is harmful to the human body; however, national investigations and regulations have not been conducted (Noh, 2016).

- According to a consumer use evaluation of disposable and reusable sanitary pads, a majority of respondents reported a degree of discomfort due to skin irritation from disposable sanitary pads. On the other hand, reusable products are good for the skin and protection of the environment. However, they noted issues such as the lack of absorbent ingredients and the struggle of washing the products. We examined recent trends in the overall use of sanitary pads through a study on the current status of menstruation and future goals of female adolescents in Gyeonngi-do. Approximately 26% of the respondents had experienced side effects from disposable sanitary pads. The incidence of skin irritation was 77.3%, and the incidence of menstrual pain was 26%. A total of 90.9% of female adolescents used disposable pads, and 7.4% used reusable sanitary pads. Only 62.5% were educated about the proper types and usage of female hygiene products. A total of 52.2% were only educated about the existence of hygiene products, which was similar to the 47.5% who were not educated at all. On the basis of similar results from other studies, such as the usage status of female adolescents for young women in Korea, it can be concluded that there is a lack of education on menstrual products, and a need to increase awareness of women’s menstrual well-being is crucial.

- Korea's menstrual activism behavior began in 2003 when the Bloody Sisters(피자매연대) started an alternative sanitary napkin movement as part of a feminist movement. The Korean Women’s Association and the Women's Environmental Solidarity conducted a campaign to make cotton sanitary napkins for ethical consumption and women’s physical health(Noh, 2016).

- Disposable menstrual products pose not only health risks, such as itching and inflammation but also significant environmental hazards. Disposable menstrual products that have already been used cannot be recycled, and gas pollutes the air when incinerating discarded disposable sanitary pads and land and water when landfilled.

- Furthermore, regarding the influence of microplastics on the climate, we found that the number of microplastics is currently increasing (Park, 2019). Owing to experimental limitations, the harmfulness of microplastics cannot be precisely determined, but because there is a potential risk, intervention is needed to prevent the occurrence and leakage of microplastics into the environment. Each disposable sanitary pad contains microplastics equivalent to the material in five plastic bags. According to research on reducing health damage from microplastics, sanitary items use polymer materials in the filter-functioning part of the product, so there is a possibility of secondary microplastics being generated and released. However, this study also revealed that respondents had a limited understanding of microplastics in personal hygiene products. In other words, most people are aware of the environmental problems caused by microplastics, but their understanding of the mechanism of microplastic contamination is limited. Therefore, promotion and education about microplastics are necessary. However, this does not lead to the conclusion that recycling is the optimal solution. This is because only 9% of the produced plastic is recycled, so up to 91% of all plastic is, in fact, not recycled properly and is discarded. The UK’s official plastic recycling rate is only 45%, and the EU’s 2020 recycling target rate is only 50%. Therefore, there is a need to reduce the use of plastic from its initial stages of production.

- 2) Interview with The Brand Hannah

- Our interviews with the Korean Menstrual Products Company Brand Hannah revealed that their sanitary pads are made of pure cotton labeled as an organic content standard (OCS) product; this means that most of the material, with the exception of the waterproof layer, decomposes. The interviewee additionally reported that, from their findings, one woman uses approximately 12,000 disposable sanitary products and approximately 120 reusable products in her lifetime. Therefore, reusable products are considered a better alternative to their disposable counterparts, which are primarily made of plastic. Furthermore, the company noted that online promotion is crucial and the most effective way to reach a broad audience of women, encouraging them to try sustainable hygiene products" for clarity and conciseness.

- 3) Monitoring the Experience of Multi-Use Menstrual Products through Survey

- The survey recruited 26 women around the age of 20, with 26 responding to Survey 1, 24 to Survey 2, and 24 to Survey 3. In Survey 1, the age range was 10 years (18--28 years), and the median was 22 years. The most common type of residence was living with family or friends (46.2%), followed by dormitories (30.8%) and living alone (23.1%) [Table 1]. In terms of exercise intensity, 46.2% of the participants responded 1--2 times a week, whereas 26.9% responded rarely and 3--4 times a week [Table 2]. The survey participants’ interest in health appropriately reflected the population. As a result of multiple responses regarding the types of menstrual products they usually use, 100% were disposable sanitary pads, 7.7% were tampons (2 people), and 3.8% were menstrual cups (1 person). Only one participant had prior experience with reusable sanitary pads. However, even those who had used menstrual cups in the past discontinued use because of increased menstrual pain. As a result of receiving responses regarding purchasing criteria and priorities for menstrual products, price ranked first, impact on health ranked second, and lack of clear standards ranked third. The percentage of consumers who were loyal to one brand or product was similar at 57.7%, whereas the percentage of those who were not loyal to one brand or product was 42.3%. The primary reason for brand loyalty was a preference for familiarity, whereas discounts were the main reason for not being loyal. The percentage of participants who experienced adverse physical effects from menstrual products was similar at 46.2%, and the percentage of those who did not experience adverse effects on the body was 53.8%. The average perceived level of knowledge about the types and uses of menstrual products was 50%, the average level of knowledge was 30.8%, and the average level of uncertainty was 15.4%.

- When asked whether they consider the impact on the environment when purchasing goods, and a significant number of participants (46.2%) responded ‘yes’. Responses to whether they consider health effects when purchasing goods also differ from expectations. It was revealed that consumers place more emphasis on their own health than on the environment. After the participants were asked to rate their perceptions of disposable vs. reusable pads on a scale of 1--5, there was no noticeable difference in their responses.

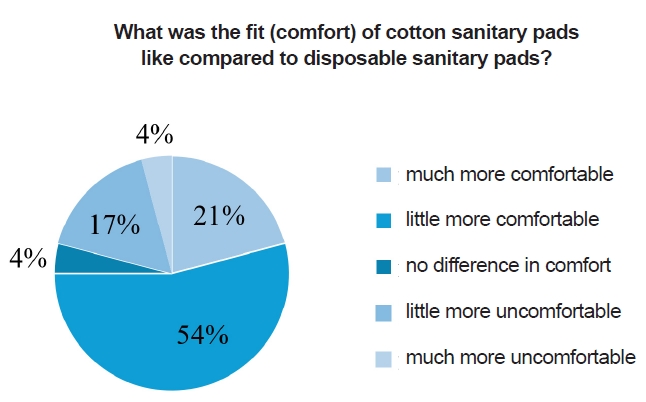

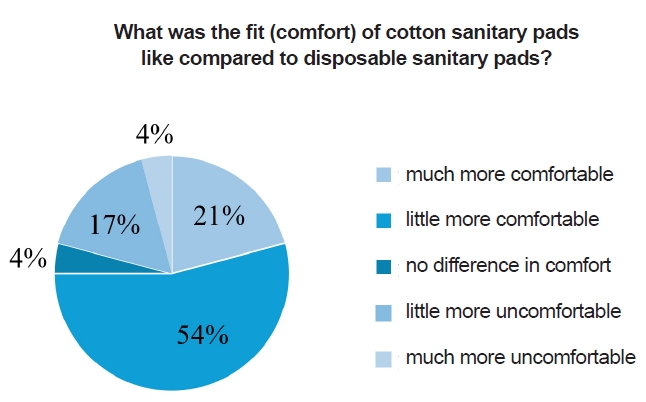

- Survey 2 asked respondents to provide feedback after using the reusable sanitary pads provided to them in the study. When asked to report tactile comfort on a 3-point scale compared with disposable sanitary pads, the majority of participants (75% (18 people) responded that they were softer. On a 5-point scale, most participants (13 people) rated the reusable pads as slightly more comfortable than the disposable pads did, whereas the second-largest group (5 people) rated them as much more comfortable [Figure 3].

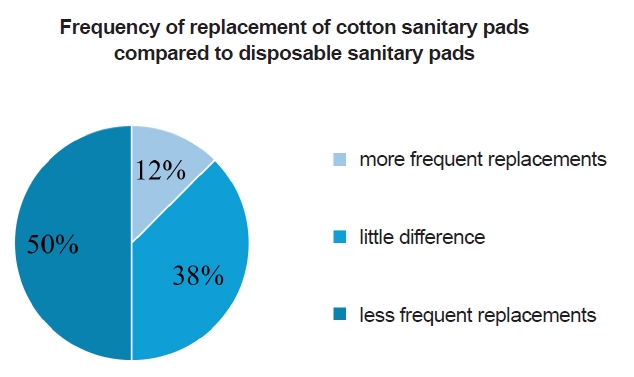

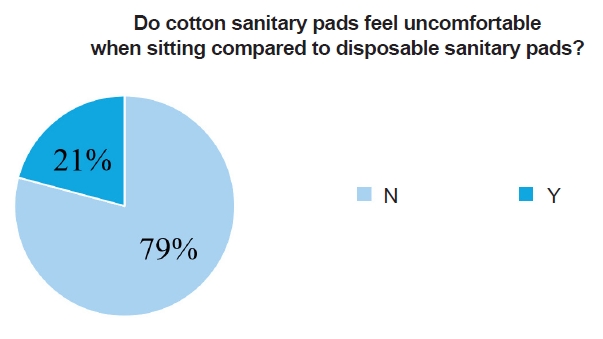

- The frequency of replacing reusable sanitary pads was lower (11 people) or similar (10 people) than that of disposable sanitary pads [Figure 4]. Compared with disposable sanitary pads, cotton sanitary pads do not produce unpleasant odors or cause discomfort when sitting (23 and 19 no, respectively). However, cotton sanitary pads cause either a very large (15 people) or a small (9 people) burden due to washing. In the other categories, there was no clear difference between cotton sanitary pads and disposable sanitary pads. When asked whether cotton sanitary pads are relatively restricted clothing, 42% (11 people) responded yes and 58% (13 people) answered no.

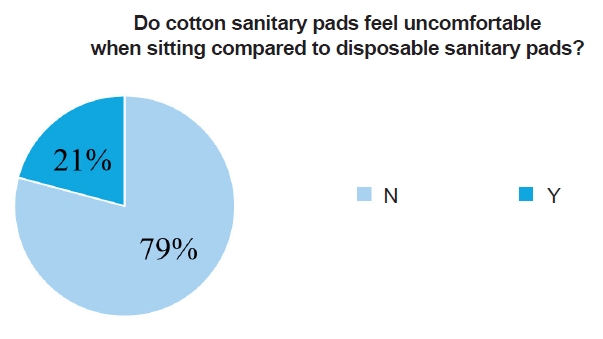

- When asked whether cotton sanitary pads were more comfortable for sitting, 79% (5 people) responded yes and 21% (19 people) answered no [Figure 5].

- However, when asked whether cotton sanitary pads were more comfortable for sleeping, 45.8% (11 people) responded yes and 50% (12 people) answered no. In this section, one participant who used menstrual/period underwear instead of disposable sanitary pads when sleeping, and thus, their response was invalidated.

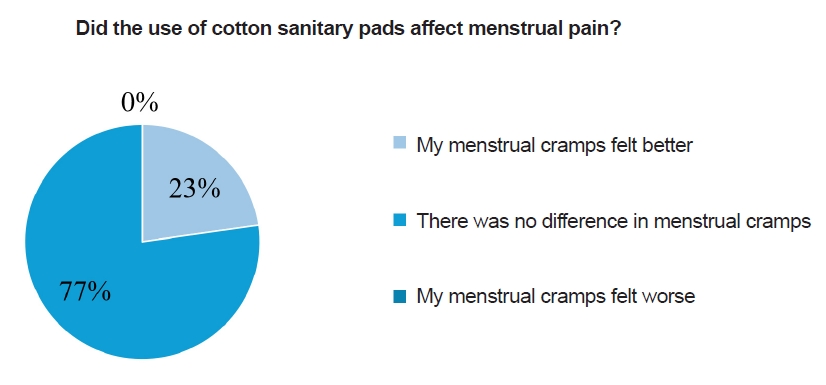

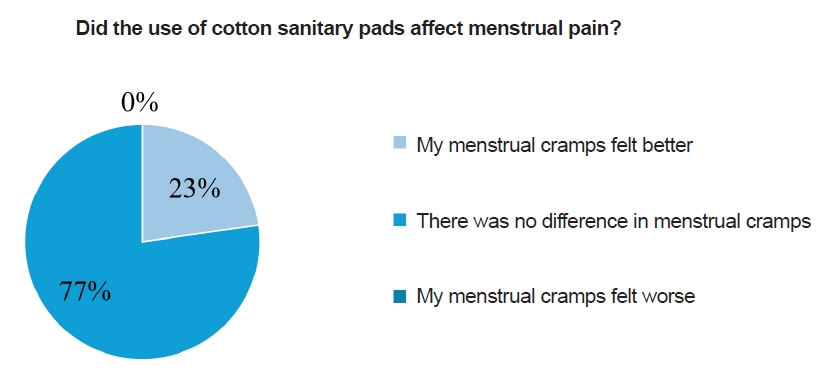

- When asked about menstrual pain, the largest number of participants (17) reported no difference in menstrual pain, whereas 7 participants reported that their menstrual pain was relieved [Figure 6].

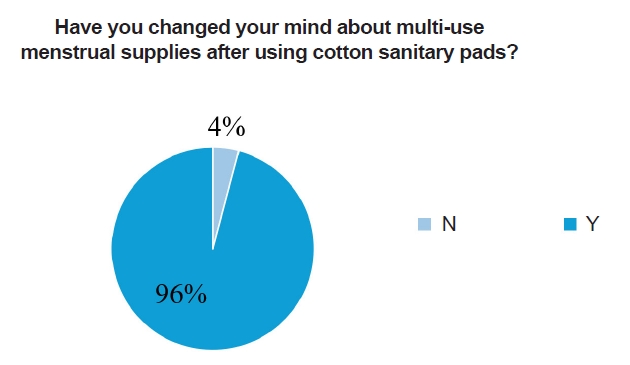

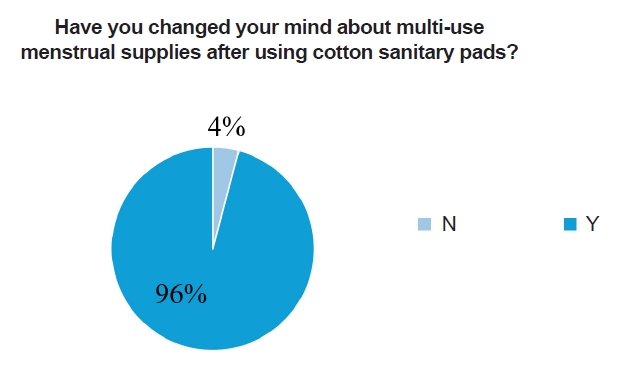

- Survey 3 participants were asked to answer after the menstrual cycle ended. Since the number of menstrual days varies from person to person, the rating of the use of sanitary pads during menstruation was reported. As a result, 20 participants used more than 1/2 of the total menstrual period, and 4 participants used less than 1/2 of the total menstrual period. Participants who used cotton sanitary pads for less than half the period of time complained of inconveniences, such as the washing of cotton sanitary pads not drying due to rain and the fact that they did not take cotton sanitary pads with them when they stayed. Most participants also used disposable sanitary pads simultaneously. The most commonly reported reasons include low absorption of cotton sanitary pads, the habit of using disposable sanitary pads, and the burden of washing. Additionally, participants were asked to write in at least 200 characters how their thoughts changed or remained the same after using cotton sanitary pads compared with before using them. Seventy-nine percent of the participants changed their thoughts positively, 13% of the participants changed their thoughts negatively, 4% of the participants felt both positive and negative, and 4% of the participants did not change their thoughts [Figure 7].

- Overall, 96% felt that their previous perceptions were moderated to some extent. This shows that most participants’ perceptions changed positively after they directly experienced cotton sanitary pads. The participants whose perceptions changed positively described improvements in skin irritation/infections and a sense of efficacy in response to climate change. Additionally, questions to determine accessibility to reusable menstrual products were included in the survey. With respect to the question about whether acquaintances or family members use cotton sanitary pads, 13% answered yes, and 87% answered no, excluding one person who did not respond. When asked on a 4-point scale how accessible they think disposable manstrual products are, 0% said it was very easy to access, 13% said it was appropriate to access, 83% said it was slightly difficult to access, and 4% said it was very difficult to access.

- This psychological distance was not a problem caused by price. When asked whether they thought the price of disposable menstrual products was appropriate, 88% said it was appropriate, and 12% said it was not appropriate. The reason why the price of reusable menstrual products is thought to be inappropriate stems from the initial cost burden or the misunderstanding that reusable menstrual products are discarded after being used three or four times.

- In addition, the participants answered questions about access to reusable menstrual products. The participants answered ‘a little hard to approach’, with 88% (21 people) answering the most. Two people answered ‘be appropriate for access’, and one answered ‘very hard to approach.’

- When asked whether they intend to continue using cotton sanitary pads or other reusable menstrual products in the future, 82.6% responded yes, and 17.4% responded no. The results indicate that after trying reusable menstrual products, participants developed positive perceptions and expressed a willingness to use them in the future.

3. Results

(1) Korea’s Menstrual Hygiene Problem

(2) Coping with Issues of Menstrual Poverty in Other Countries

(3) The issue of Menstrual Poverty in Korea

(4) Safety Issues of Disposable Menstrual Supplies

(5) Menstrual Safety and Well-being of Korean Women

(6) Current Status of Menstrual Hygiene in Korea

(7) The Harm of Disposable Menstrual Products to the Environment

- Many participants recognized that access to reusable menstrual products was slightly difficult. Further follow-up studies are needed to explore this issue. However, this study aimed to determine whether women would continue using reusable menstrual products in the future after experiencing them under the given conditions.

- While awareness of environmental issues is increasing, there is still significant room for improvement regarding the excessive use of disposable menstrual products. On the basis of our first survey, 100% of the participants responded that they were using disposable pads, whereas 42.6% responded that they took the environment into account when consuming products. We interpret that the communication and flow of discourse about menstruation is still yet mainstream in society, and hence, it is more difficult to attempt to use reusable products for the first time. If we break that barrier and gradually increase accessibility, it is likely that we can accentuate the long-term benefits of sustainable female hygiene products.

- The first problem in this study is that the sample size for the monitoring and questionnaire studies was small. This study analyzed the final responses of 24 people and needs to analyze larger samples in the future. While conducting the survey research, we encountered an unexpected problem. Because Survey 1 was answered anonymously in the form of an online Google questionnaire, dropouts could not be excluded from the results of Survey 1. An online form was used to ensure participant convenience and anonymity, but the research was also disrupted. To account for these shortcomings, in Surveys 2 and 3, names were written and sent by individual email. The participants were informed in advance that they would be asked to provide their names to confirm submission, while the survey responses would be kept anonymous.

- If we study more participants, we will be able to determine whether interest in and practices related to health are correlated with Survey 1's perception of the use of multiple menstrual products. In addition, participants will be classified according to their type of residence and the presence or absence of cohabitation to assess potential correlations with the use of multiple-use menstrual products.

- Despite many shortcomings, this study helps us understand the practical limits and perceptions of women in our local community and how we should approach this problem.

- According to the literature, the problem of menstrual hygiene is currently ignored in Korea, and many female adolescents in Korea have difficulty purchasing menstrual products for economic reasons. Payment of multiple-use menstrual products will reduce the cost of disposable menstrual products.

- The efforts of other countries to create an environment in which women can properly manage menstruation were examined in terms of national policies and corporate projects. In this process, it was confirmed that addressing menstrual hygiene requires both health education and the establishment of hygiene infrastructure and support for menstrual products. The international relief organization 'Plan International' presents the cost of menstrual products, lack of menstrual education, and stigma as the causes of menstrual poverty. Educating adolescents about menstruation can help bring menstrual issues into visible social discourse. Multiple-use menstrual products should be activated for women's physical health, ethical and rational consumption, and daily climate change response practices.

- Survey 1 revealed low customer loyalty to sanitary pad products or companies, with unclear purchase criteria. In other words, customers purchase menstrual products very fluidly. Through proper education and active communication about menstruation, multiple menstrual products can be activated. We concluded that through a wider promotion on social media and opening more offline stores or events for women to first handedly see and experience reusable products, the problem could be targeted. We plan to consistently upload and share accessible and easy-to-understand information about feminine hygiene products in the future and possibly collaborate with companies to open pop-up stores at our university. We aim to pay more attention to different ways of targeting sustainability within our consumption of products. Awareness of the environment is gradually expanding, and sustainable consumption trends are increasing, but it is expected that it will take some time until sustainable products become mainstream. Therefore, both online and offline platforms must be used to promote the goals of the project. As awareness of microplastics spreads, so will awareness of climate change across various aspects of society. Additionally, if the consumption of eco-friendly menstrual products increases, it could significantly reduce waste over time and minimize pollution from landfills and incineration.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Table 1.Type of Residence

| Type of Residence | |

|---|---|

| living with family or friends | 12 |

| dormitories | 8 |

| living alone | 6 |

Table 2.Exercise Frequency

| Exercise Frequency | |

|---|---|

| more than 5 times a week | 0 |

| 3-4 times a week | 7 |

| 1-2 times a week | 12 |

| less than once a week | 7 |

- House, S., Mahon, T., & Cavill, S. (2015). Menstrual hygiene matters: A resource for improving menstrual hygiene around the world. ACF, CARE, IRC, Oxfam, Plan, Save the Children, SHARE, UNICEF, USAID, WASH, WaterAid, World Vision.

- Jeon, E., & Moon, J. (2014). Analysis of user sensitive evaluations of disposable and reusable sanitary pads. The Korean Society for Emotion & Sensibility, 17(2), 77-84.

- Jung, H. W. (2019). The menstrual status and future tasks of female adolescents in Gyeonggi-Do (Issue Analysis, Vol. 141). Gyeonggi Do Women & Family Foundation.

- Lee, U. K. (2020, December 30). The 2020 sanitary pad quality monitoring results were announced. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. https://www.mfds.go.kr/brd/m_99/view.do?seq=43884

- Noh, J. E. (2016). A study on transboundary activism and the sexually regenerated industrial health area (SRHR) in Asia (Master's thesis). Ewha Womans University.

- Panjwani, M., Rapolu, Y., Chaudhary, M., Gulati, M., Razdan, K., Dhawan, A., & Sinha, V. R. (2023). Biodegradable sanitary napkins—a sustainable approach toward menstrual and environmental hygiene. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-023-02345-5Article

- Park, E., & Bae, J. (2020). The use and perception of menstrual hygiene products among female adolescents in Korea. Public Health Weekly Report, 13(10), 531-543.

- Park, J. G., & Park, H. N. (2019). A study on risk management of microplastics. Korea Environment Institute. https://www.kei.re.kr/eng/research/report/view.do?boardId=3&menuId=6&contentId=12345

- Shin, S. W. (2022). A legal research for the protection of human health and environment from microplastics (Master's thesis). Hanyang University.

- Son, J. (2023, May 26). Korea faces calls for universal free menstrual products amid low birthrate. Korea Herald. https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20230526000466

- Vostral, S. L. (2008). Under wraps: A history of menstrual hygiene technology. Lexington Books.

References

Appendix

Figure & Data

References

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

IGEE

IGEE

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite