Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > IGEE Proc > Volume 2(2); 2025 > Article

-

Article

Analysis of the Correlation Between Health Status and Social Factors Among Korean Care Workers† - YeJin Yun1*, Yuna Kim2, Miyeon Yoon2, Sejin Park1

-

IGEE Proc 2025;2(2):114-132.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.69841/igee.2025.018

Published online: June 30, 2025

1College of Medicine, Yonsei University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

2College of Nursing, Yonsei University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

- *Corresponding author: YeJin Yun, E-mail: mabukbayang919@yonsei.ac.kr

- †This research is supported by the Social Engagement Fund (SEF) 2024.

• Received: May 18, 2025 • Revised: May 30, 2025 • Accepted: June 9, 2025

© 2025 by the authors.

Submitted for possible open-access publication under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

- 850 Views

- 20 Download

Abstract

- Amid South Korea’s demographic crisis of a declining birth rate and a rapidly aging population, care work has become an essential yet undervalued sector. This study investigates the physical and mental health conditions of domestic care workers and explores how social and structural factors shape their labor experiences.Using a mixed-methods approach, the research integrates survey data from care workers (n=345) with in-depth interviews of nine individuals working in various care roles, including certified caregivers, disability support workers, childcare teachers, and domestic workers. Quantitative findings reveal strong correlations between job satisfaction and health outcomes. Higher job satisfaction was associated with lower scores on the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), indicating better physical and mental health. Significant disparities were found between care worker subcategories. Qualitative analysis further uncovered recurring themes such as emotional burden, social invisibility, dissatisfaction with compensation, and the absence of grievance mechanisms. Despite these challenges, many workers found meaning in their roles and relied on informal coping strategies such as peer support. This study underscores the urgency of addressing systemic issues in the care sector. The results call for policies that improve working conditions, recognize the social value of care work, and promote health equity. The findings contribute to advancing Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 3(Good Health), 5 (Gender Equality), and 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth).

- Purpose and significance

- Korean society has been experiencing a population crisis as it faces a low birth rate and an aging population. The reversal of the proportion between the 0-14 age group and age 65 or older group is expected to be worse, and by 2050, the population who is aged 65 or older is expected to account for 40.1% of the total population (Statistics Korea, 2025).

- Changes in the demographic structure due to low birth rate and population aging require a conversion in the care work paradigm. First, care work includes activities such as housework, health care, childcare, and elderly care, and focuses on providing physical, emotional, and psychological support to maintain and promote individual health and well-being (Lee, 2012). As socio-economic conditions change rapidly, the demand for care work has become visible and the importance has emerged. However, compared to changes in demand, supply is not keeping up with it. There are a few policies and services for continuous supply of care workers, though. Care work differs fundamentally from general forms of labor. Distinctive characteristics of care work include the prevalence of late-night shifts, rotating schedules, and extended working hours. The harsh reality has made the current situation worse.

- Recognizing these problems, Korea has made efforts to increase the number of support targets for care services, such as expanding child allowances and childcare services, preparing care leave systems, and guaranteeing the time spent on care work. In 2021, the Care Workers Support Act was proposed. Nevertheless, the fact that the frequency of emotional problems and depressive symptoms among care workers is remarkably high.

- Considering that more than 60% have musculoskeletal diseases and 25% have sleep disorders still present health problems (Park. et al., 2013), it is also suggested that there is a long way to go to improve the treatment of care workers. With this problematic situation unsolved, on March 5, 2024, the Bank of Korea decided to allow foreigners to work in care work system and announced a plan to ease the labor shortage and cost burden of care services.

- The government's policy about foreign care workers seems reasonable. However, it is just seen as a temporary measure to the current situation, considering that there were insufficient attempts to solve why the care work market is always incomplete.

- As mentioned above, the demand for care work continues to increase as the social structure has been changed. However, there is a gap between supply and demand of care workers, as the supply is delayed due to inappropriate working conditions. Although various attempts have been made at the government level, the government's attempts have not been effective as it has not identified the underlying causes and the experiences of care workers and has not reflected their opinions in the discourse. Therefore, the study using in-depth interviews and surveys on care workers must be conducted in terms of analyzing their work experiences in detail and finding specific meaning in their experiences.

- Objective of the study

- Through this study, we intend to explore the job experience related to physical / mental health and find important implications quantitively and qualitatively. Identifying the correlation between the health factors of the care workers through a survey and statistical analysis, we will investigate the work experiences of care workers through in-depth interviews and trace their work status microscopically.

- SDGs

- Having established the demographic and policy context, it is now important to consider how these challenges intersect with global development priorities, particularly the Sustainable Development Goals.

- The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted by the United Nations in 2015, represent a global commitment to advancing progress across various areas—such as health, gender equality, economic growth, and the reduction of inequality—by the year 2030 (Griggs. Et al, 2017). In response, many countries have developed and implemented national strategies tailored to their specific circumstances. This study aims to contribute to the achievement of SDGs 1 (No Poverty), 3 (Good Health and Well-being), 5 (Gender Equality), 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), and 10 (Reduced Inequalities) by analyzing the correlations between the health status of care workers in Korea and relevant social factors.

- Focusing primarily on SDG 3, this research explores the health and well-being of care workers, while also addressing the growing importance of care work in the context of Korea’s low birth rate and aging population. Given the high proportion of older women and migrant workers in the care workforce, the study further aligns with SDG 5 by addressing gender-based disparities and the economic empowerment of women. Additionally, it reflects the goals of SDG 8 and SDG 10 by highlighting challenges related to wage inequality and structural disparities. Through this analysis, the study seeks to provide policy implications that can contribute to improving the livelihoods and social recognition of care workers.

1. Introduction

- With the study’s alignment to the SDGs clarified, the following section reviews existing literature to contextualize care work in Korea and highlight key issues faced by workers in this sector.

- Definition and Characteristics of Care Work

- Care work is divided into the public and private areas. In the case of the private area, it includes nursing, housework management, postpartum care services, and childcare services. Especially, the majority of care workers employed in the private sector are classified as informal workers, lacking formal labor contracts and guaranteed terms of employment (Yoon, 2013).

- As a result, various legal and institutional attempts have been made to improve the treatment of care workers, but there are several legal issues - for example, The status of care workers Whether self-supporting workers are recognized as employees -, so a clear conclusion has not been derived (Yoon, 2013).

- It is also explained that care services have some differences in service systems, unlike general services or manufacturing industries. Therefore, it is found that care workers’ mental and physical burden about their work is very high (Park et al., 2013).

- Working as Domestic Workers

- It is found that there are several cases of depression (35.5%) due to mental stress caused by emotional labor and sexual harassment (23.4%) while working as domestic workers. According to an in-depth interview conducted later, even if such emotional and mental damage is big, it is often aggravated by the absence of a grievance system or attempts to resolve it. Although laws such as the Seoul Labor Safety and Health Support Ordinance and the Seoul Metropolitan Government Emotional Workers Protection Ordinance are in place currently, the details are still insufficient and vague (Lee et al., 2024).

- Working as Patient Caregivers

- It is stated that patient caregivers are introduced through intermediaries or platforms (company) to work. It was also explained that the patient caregiver brokerage company performs tasks only for simple employer-employee matching, without considering working conditions. In addition, it is mentioned that patient caregivers often perform not only ‘official care work’ described by the National Statistical Office but also some medical works such as aspiration or wound dressing (Hwang & Jung, 2023).

- Working as Childcare Teachers

- It is emphasized that working as childcare teachers needs considerable physical and mental health, and the teachers are required to perform childcare activities as well as infant protection, various tasks for a long time, for example, textbook teaching management and facility management. They experience a lot of stress due to fatigue and work burdens caused by job characteristics that require a high level of emotional interaction. Eventually, these stresses have a great impact on the teacher’s mental health (Koo & Park, 2013).

- Working as Child-care Providers

- It is found that 60.5% of participants answered ‘No’ for whether their musculoskeletal diseases have been treated during the past 6 months. 53.7% of participants answered ‘Yes’ for whether they have visited hospitals due to their diseases. 60.8% of participants answered ‘Yes’ for whether they have diagnosed diseases, which included herniated disc, hypertension, arthritis and so on. In addition, 74.5% answered that they have pain, which occurs at their back, shoulder, hand/arm, feet/leg (Lee et al., 2014).

- Working as Certified Caregivers

- According to a study about the physical burden of certified caregivers working in long-term care nursing facilities, the rate of experience with their musculoskeletal diseases was 15.9% over the entire period and 11.3% over the past year. In addition, musculoskeletal diseases are one of the representative work-related diseases of certified caregivers, often caused by repetitive movements, inappropriate working pos-ture, and excessive use of force. It was also confirmed that chronic pain or sensory abnormalities may appear in the neck, shoulder, waist, upper/lower muscle, and surrounding body tissues (An, 2023).

- Working as Disability Support Workers

- It is revealed that the prevalence of musculoskeletal diseases in the back, shoulder, neck, and wrist during the job performance was highly reported by disability support workers (Lee & Kim, 2023). It is explained that disability support workers are hourly wage workers, and their pay is close to the minimum wage (Kim, 2022). The wide range of job responsibilities causes job stress, and previous studies examining the relationship between job stress and psychological well-being among these workers are very limited (Hwang & Han, 2024).

2. Literature review

- Building on the insights from previous research, the next section outlines the materials and methods used in this study to systematically investigate the health and social factors affecting care workers.

- Materials

- The survey paper used for the quantitatve research is attached as a part of Supplement. The interview questions used for qualitative is attached in Supplementary Table S1.

- Methods

- A mixed-methods study was employed, combining qualitative and quantitative research methods. Both approaches were done simultaneously.

- Quantitative Research: Data was collected through a survey on the health status of care workers, followed by an analysis to identify significant results between variables.

- Quantitative Research: In-depth interviews were conducted to identify expressions of job recognition in various categories.

- Participants

- The participants were defined as current or former care workers in South Korea whose age is between 18 and 69 years. To recruit proper participants, recruitment was done through online careworker communities such as ‘Naver Cafe’, and ‘Naver Band’, social welfare organizations, and carework labor unions. This study employed a mixed-methods approach, incorporating quantitative data from survey responses of care workers (n=345) and qualitative insights from in-depth interviews with a total of nine care workers (n=9).

- A survey was conducted with care workers (n=345) using both online and offline methods. The survey collected responses related to various factors, including detailed occupation type, age, gender, wage, education level, household income, number of household members, whether they are the head of the household, leisure time, chronic illnesses, health issues (e.g., back pain, anxiety, depression), job satisfaction, job stress, caregiving frequency, caregiving hours, differences between actual working hours and contracted working hours, night shifts, frequency of night shifts, and overall satisfaction.

- Mental and physical health status were assessed using validated instruments: The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depressive symptoms (range: 0–27), the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale for anxiety symptoms (range: 0–21), and the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) for lower back pain-related disability (expressed as a percentage, with higher scores indicating greater impairment).

- Content analysis based on interviews with 9 care workers Interviews were also conducted. Six main questions, and several detailed questions related to topics such as: job content, reasons for choosing the job, physical and mental health issues triggered by work, compensation, work environment, and driving force for job continuity were asked.

- Analysis

- Care workers were categorized into detailed occupation types, including certified caregivers, child-care providers, domestic workers, disability support workers, and others. Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed to analyze differences between occupation types regarding age, wage, working hours, job satisfaction, job stress, and health scores. Dunn's Test was then used to determine if the differences between the groups were statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 4.4.1.

- The interview was then analyzed based on frequently mentioned themes, including general characteristics, recruitment process, entry process, wage perceptions, job perceptions, and the impact on mental health.

3. Materials and Methods

1) Quantitative research

2) Qualitative research

1) Quantitative research

2) Qualitative Research

- Quantitative Research

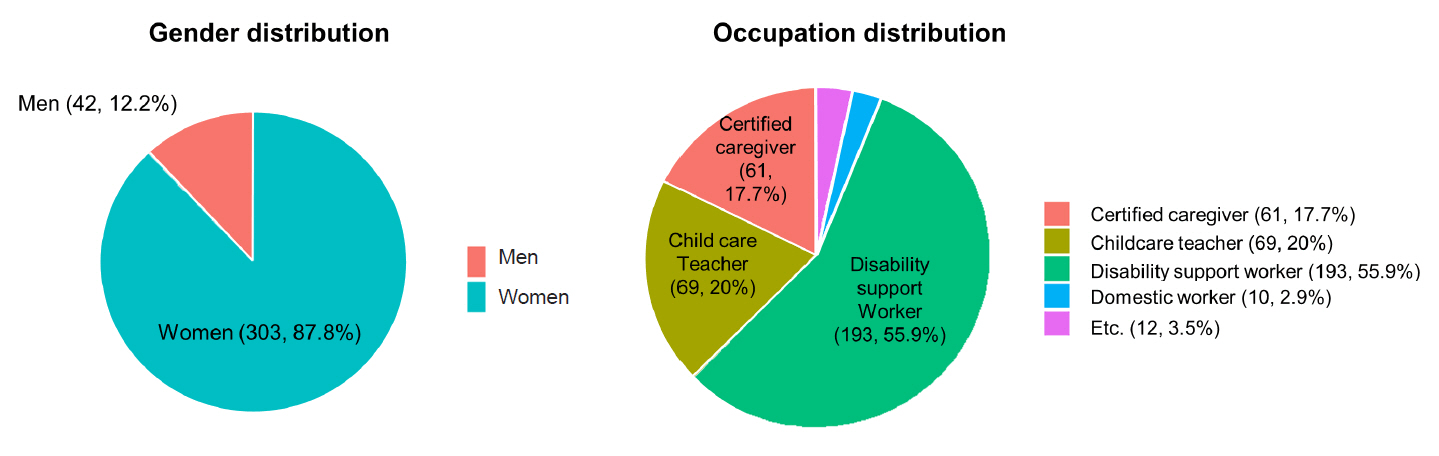

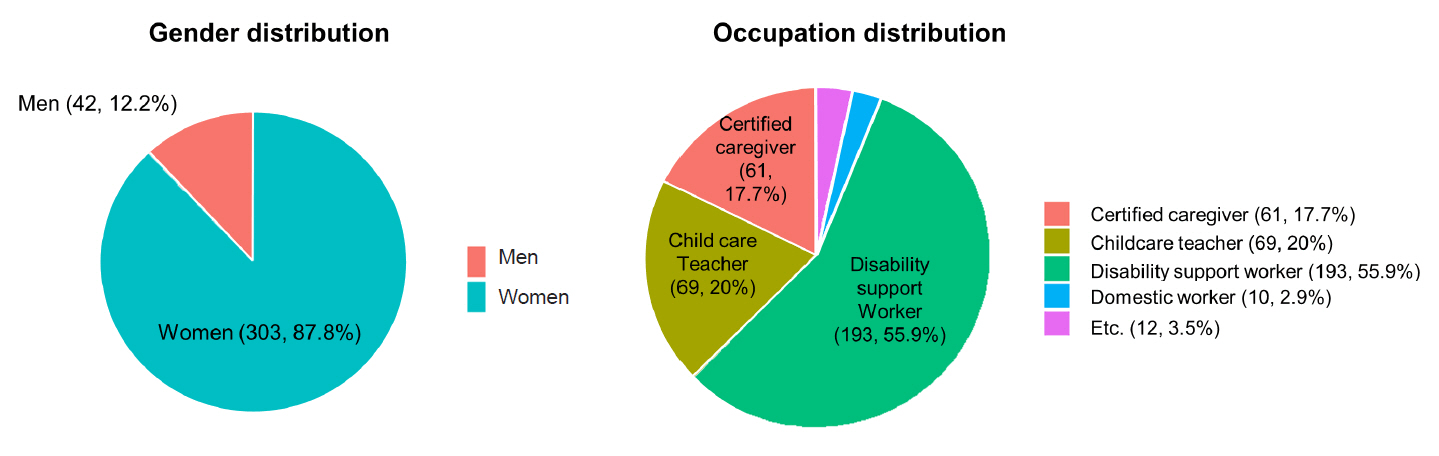

- The survey respondents (n=345) included 42 men (12.2%) and 303 women (87.8%). In terms of job category distribution, disability support workers made up the largest proportion (193 respondents, 55.9%), followed by childcare teachers (69 respondents, 20%), Certified caregivers (61 respondents, 17.7%), domestic workers (10 respondents, 2.9%), and others (12 respondents, 3.5%) as shown in Figure 1.

- Figure 2 shows the general characteristics of the survey participants. Among the survey respondents, 133 individuals (29.2%) identified themselves as the primary income earner of their household, meaning that the majority were not the main breadwinners. Regarding wage satisfaction, the most common responses were "neutral" (127 respondents, 37.5%) and "satisfied" (118 respondents, 34.8%). In terms of educational attainment, the highest proportion of respondents had attended or graduated from university (195 respondents, 57.5%). Among chronic illnesses, hypertension had the highest number of responses, with 59 individuals (17.1%) reporting the condition.

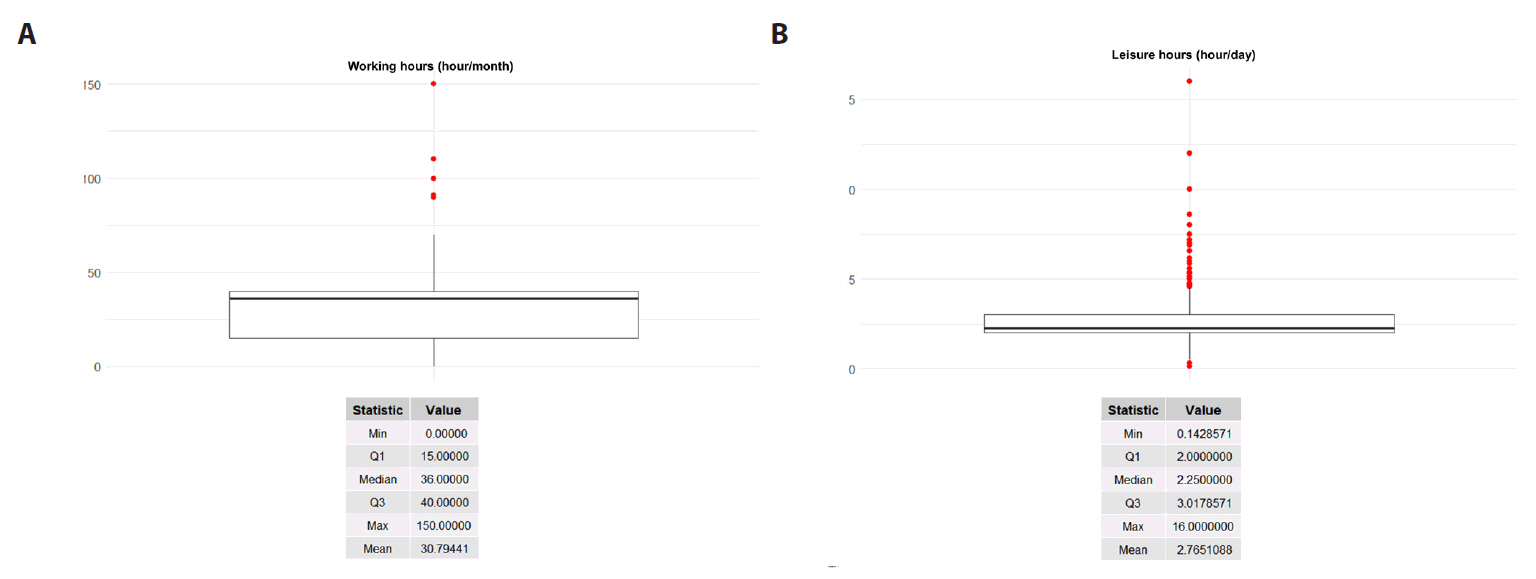

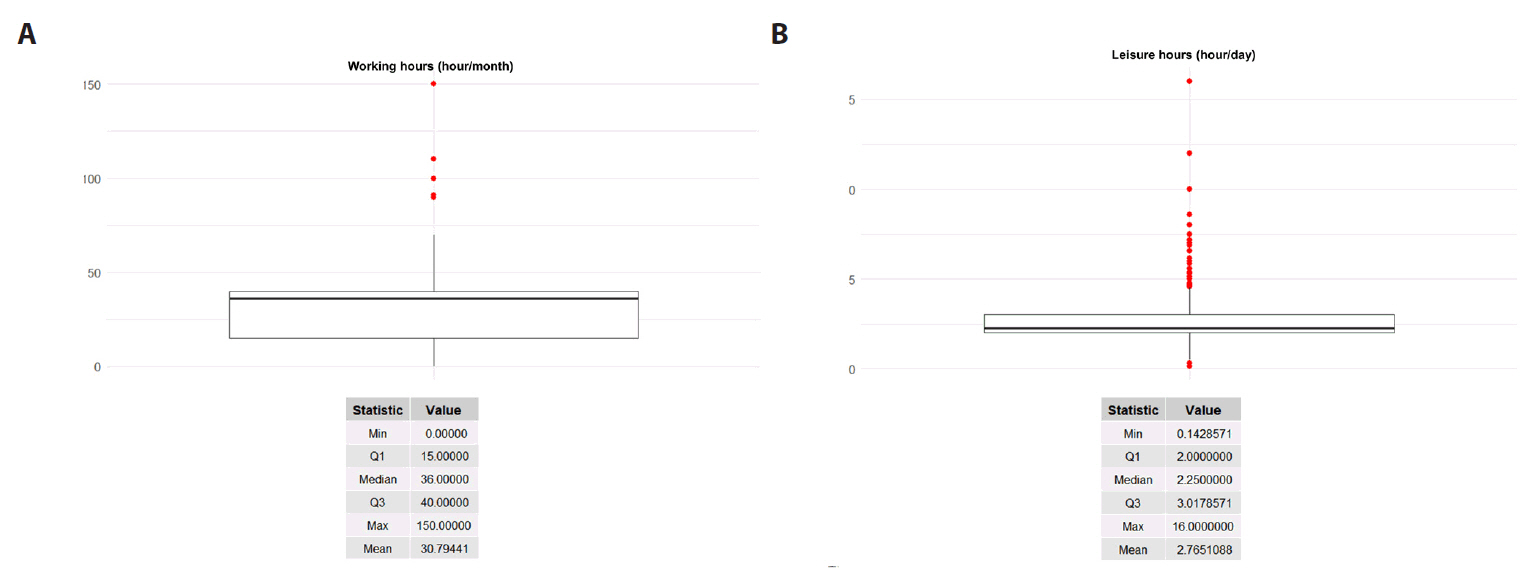

- In Figure 3, the median and mean of participants' working hours and leisure time are shown. Working hours were measured based on the question: "Over the past month, how many hours per week, on average, did you engage in care work?" The median working hours were 36 hours, while the average working hours were 30.8 hours per week. The maximum recorded working hours were 150 hours. In response to the follow-up question: "Over the past three months, was there a difference between your actual working hours and the contracted working hours?", 56 respondents indicated that there was a discrepancy, suggesting that reported working hours may differ from either contracted or actual working hours. Regarding leisure time, responses to the question: "Over the past year, how many hours per day, on average, did you have for leisure? (Leisure time refers to free time before or after obligatory activities such as eating, sleeping, working, and household chores.)" showed a median leisure time of 2.25 hours and an average leisure time of 2.78 hours per day.

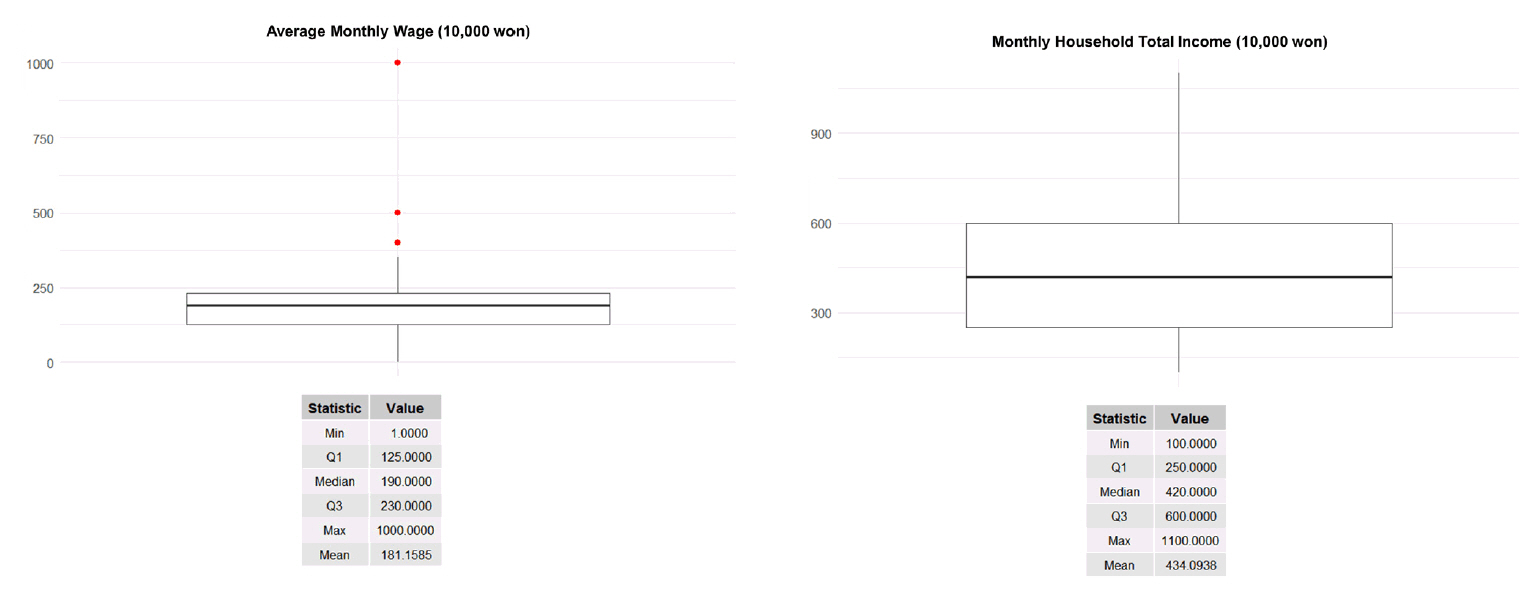

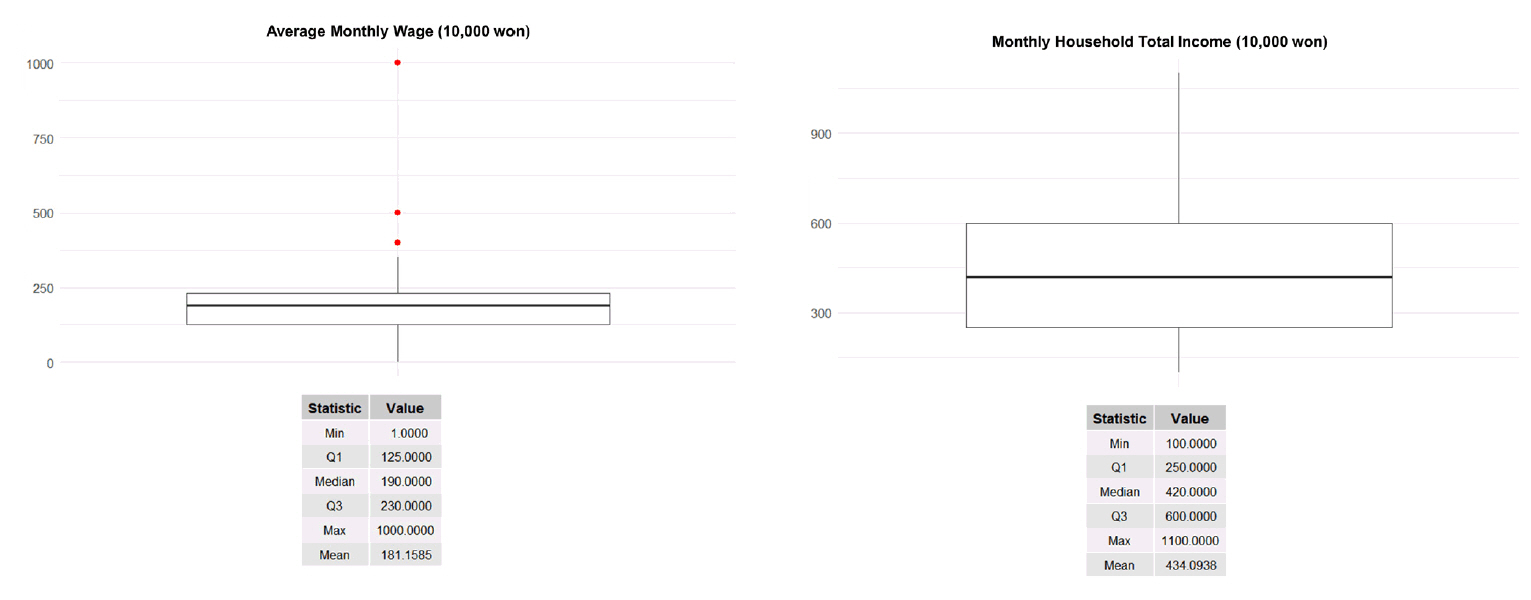

- For the question regarding average monthly wage, the responses showed a median of 1.9 million KRW and an average of 1.81 million KRW. For total household monthly income, the responses recorded a median of 4.2 million KRW and an average of 4.34 million KRW as shown in Figure 4.

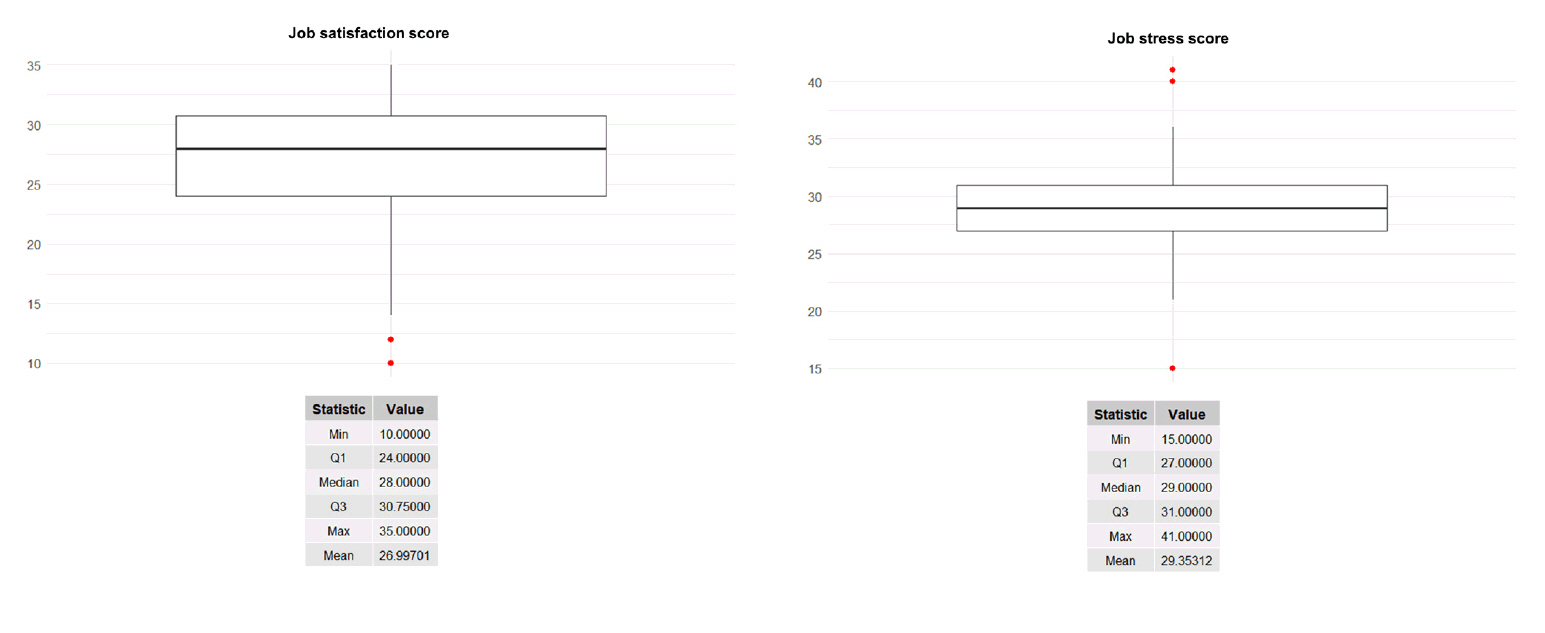

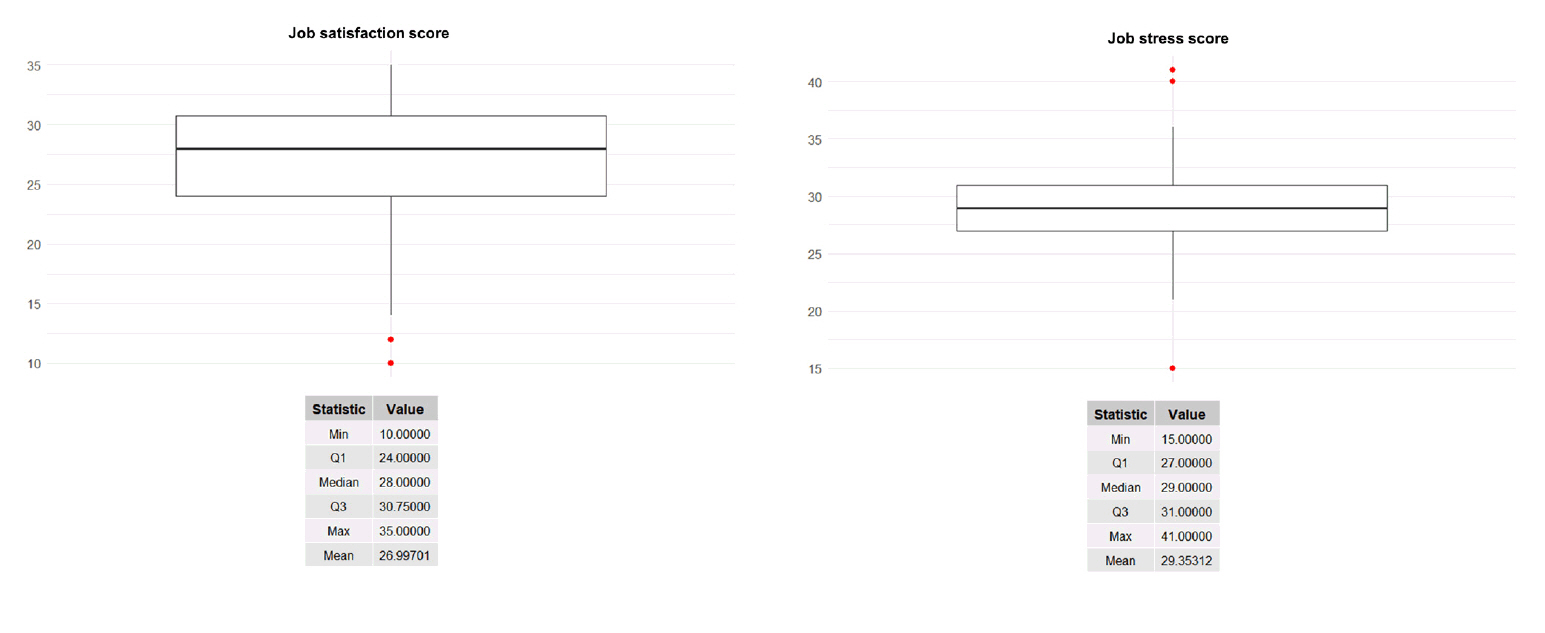

- The job satisfaction score had a median of 28 points, while the job stress score had a median of 29 points as shown in Figure 5.

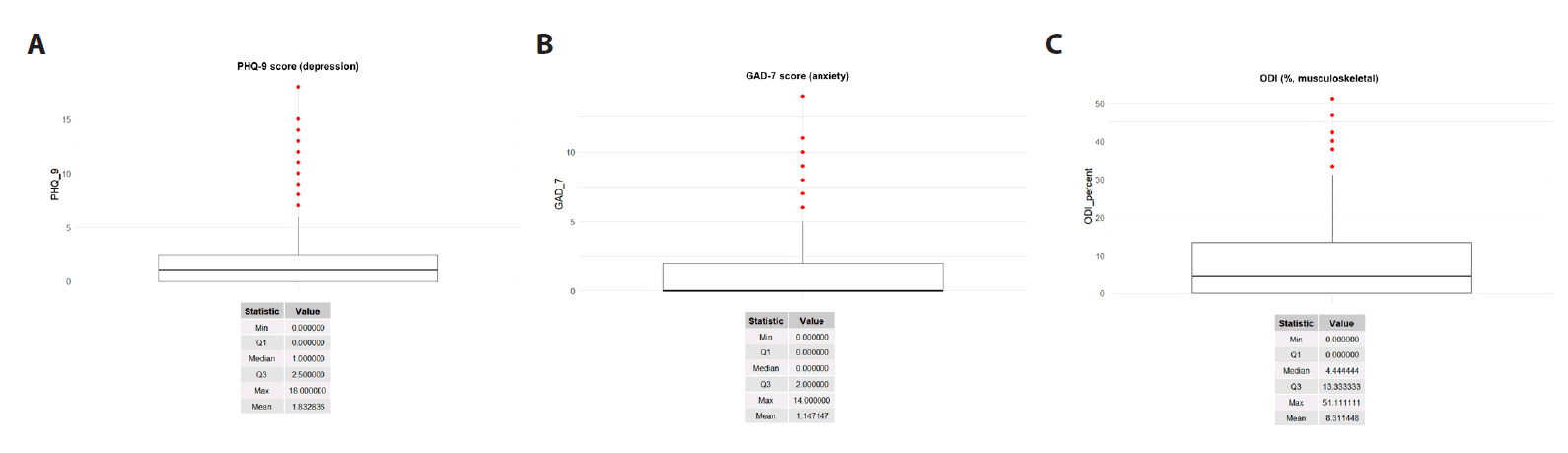

- The PHQ-9 score had a median of 1 point, the GAD-7 score had a median of 0 points, and the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) (%) score was 4.44 points as shown in Figure 6.

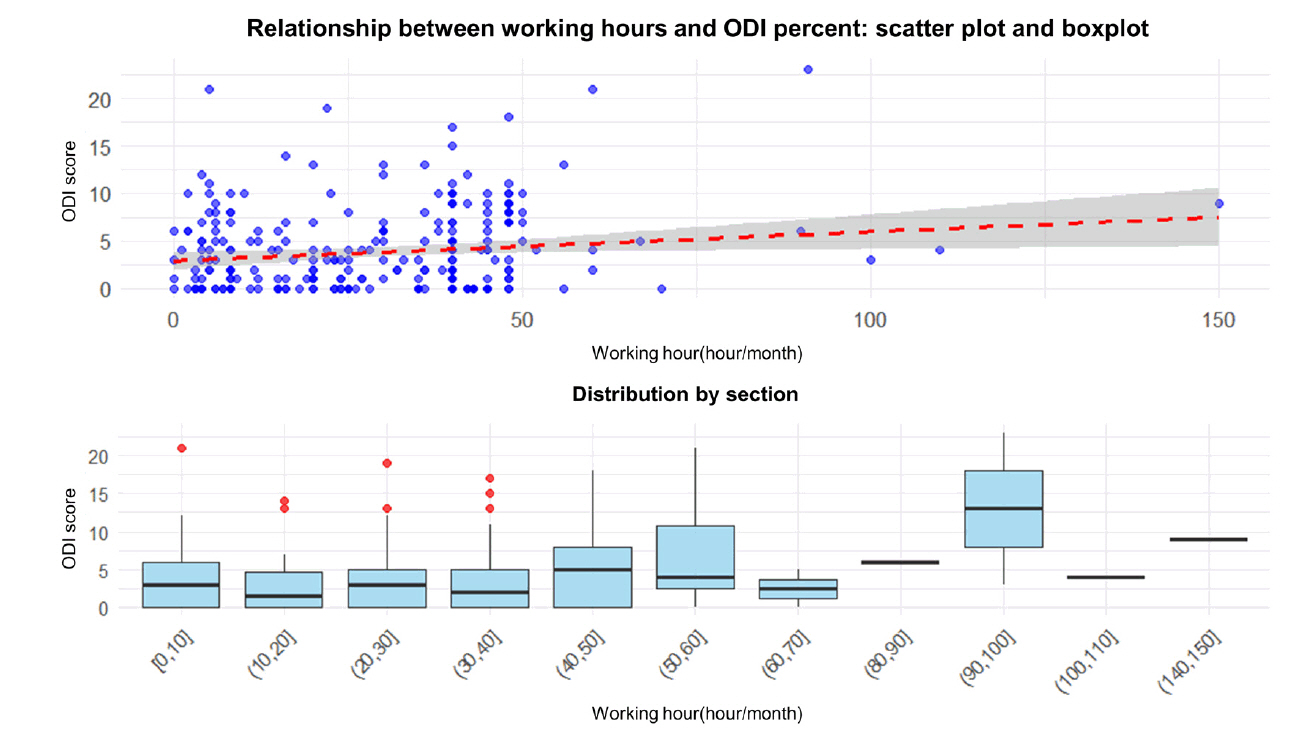

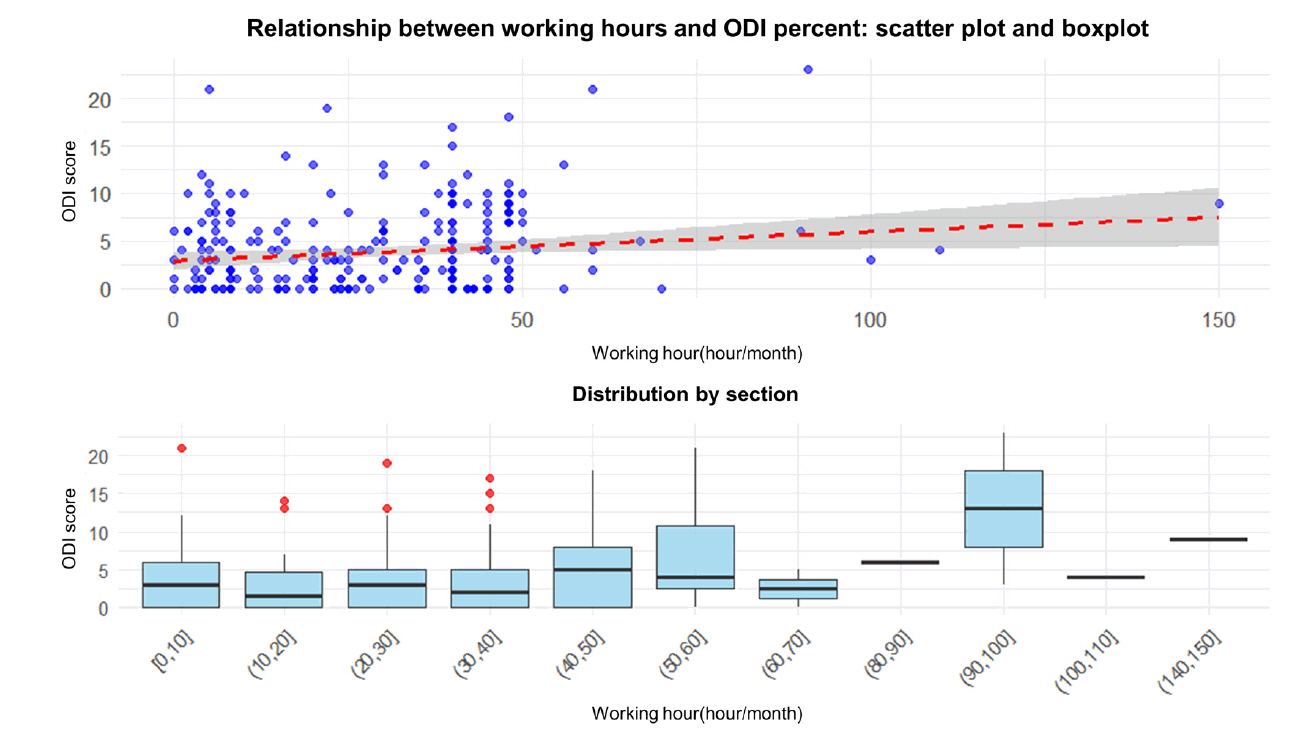

- Figure 7 shows that longer working hours are associated with lower ODI percentage scores (slope: 0.031, R square: 0.019, P value: 0.10188). A higher ODI percent score indicates more severe lower back pain. While it can be inferred that severe lower back pain may limit working hours, the correlation is not clearly defined based on the distribution. Therefore, further research with a larger sample size is necessary.

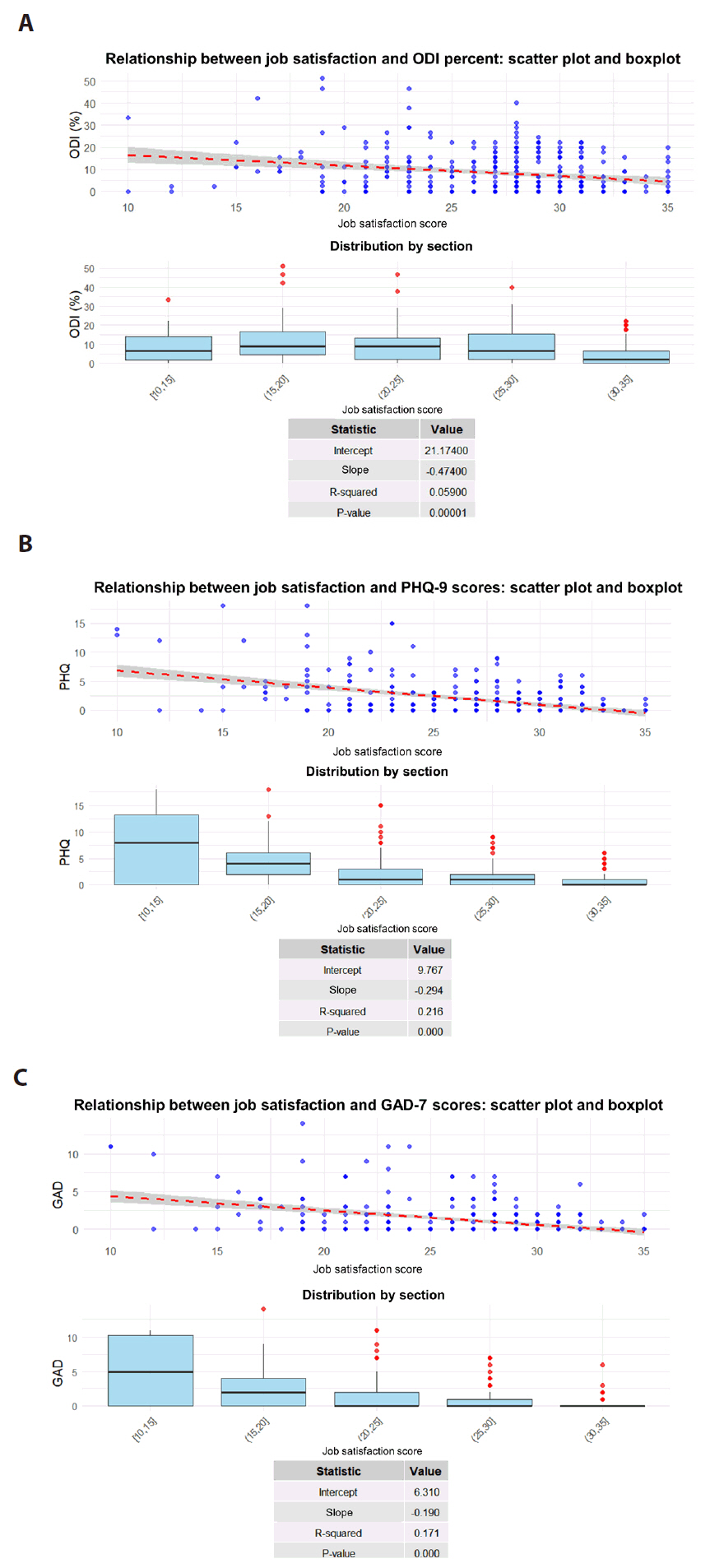

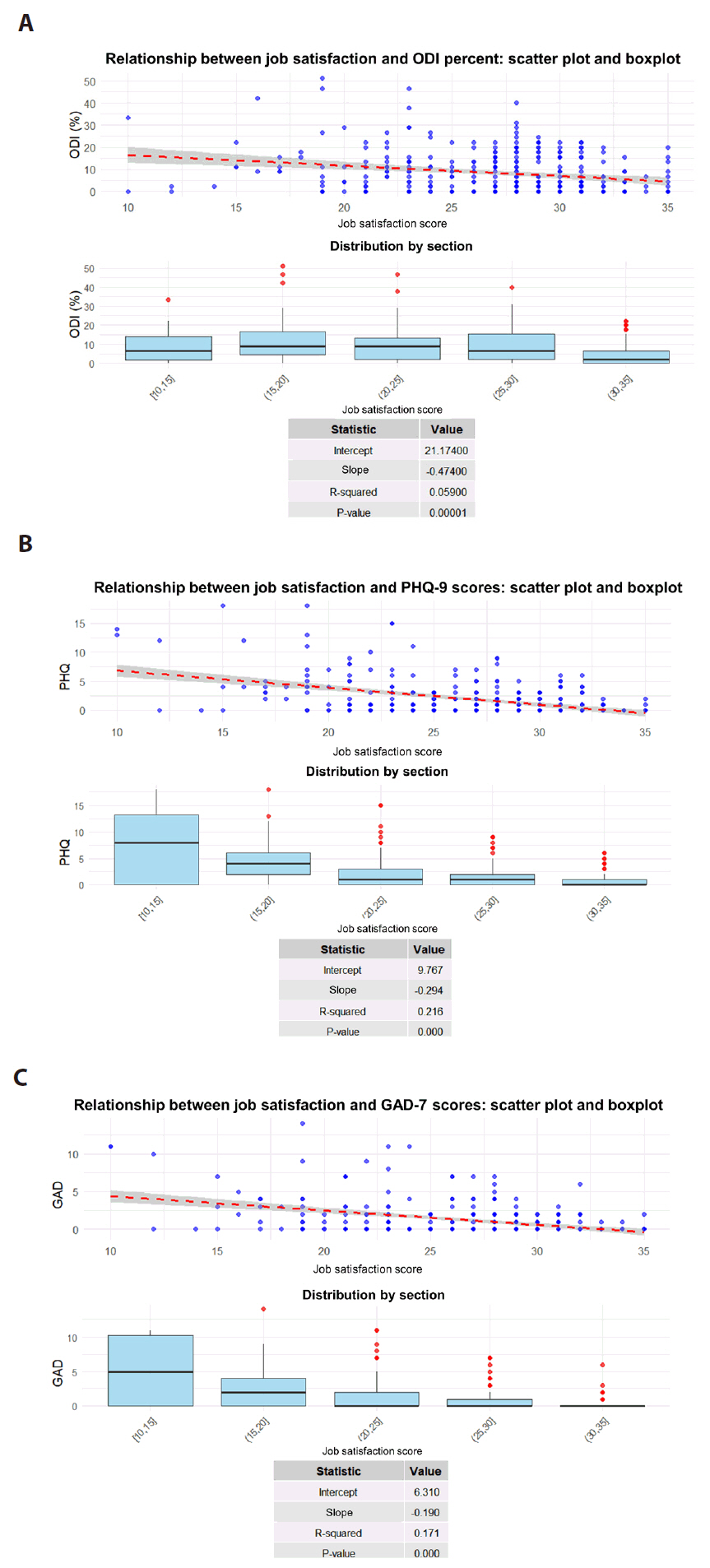

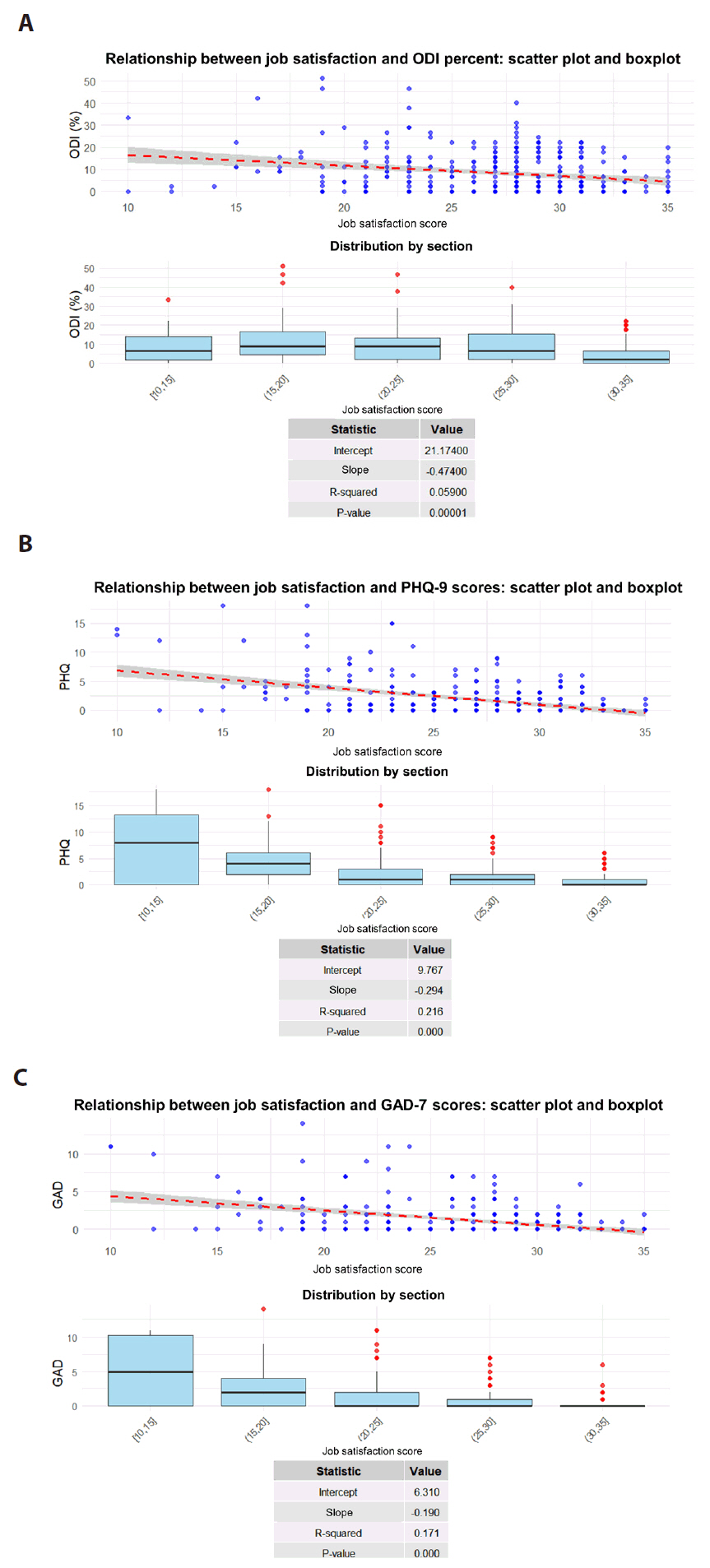

- Figure 8 demonstrates that the higher job satisfaction scores are correlated with lower ODI percent, PHQ score and GAD scores. Since lower ODI percent, PHQ, and GAD scores indicate better health, it can be inferred that being in good health contributes to higher job satisfaction. Conversely, low job satisfaction may have a negative impact on mental health, further reinforcing this correlation.

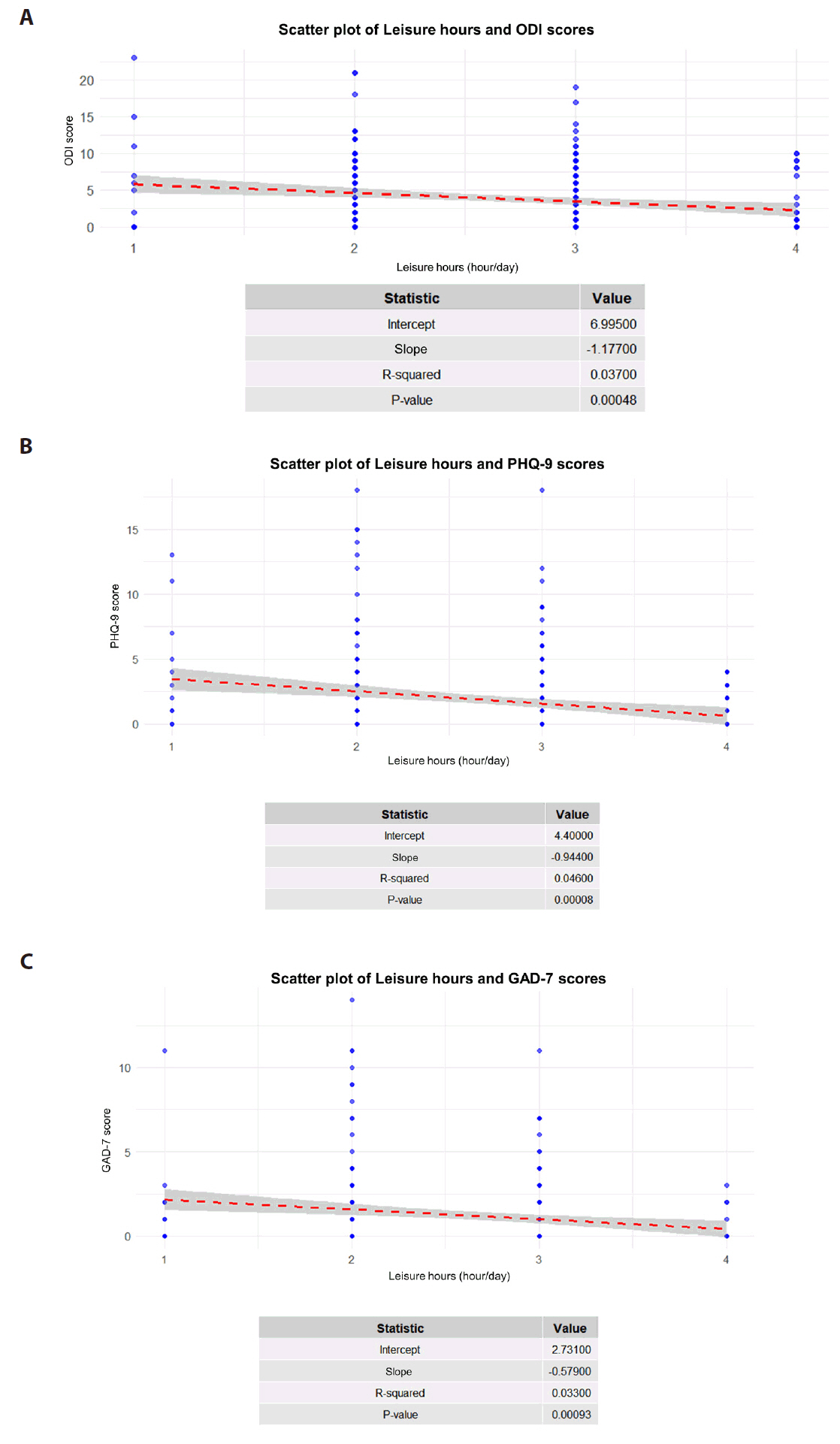

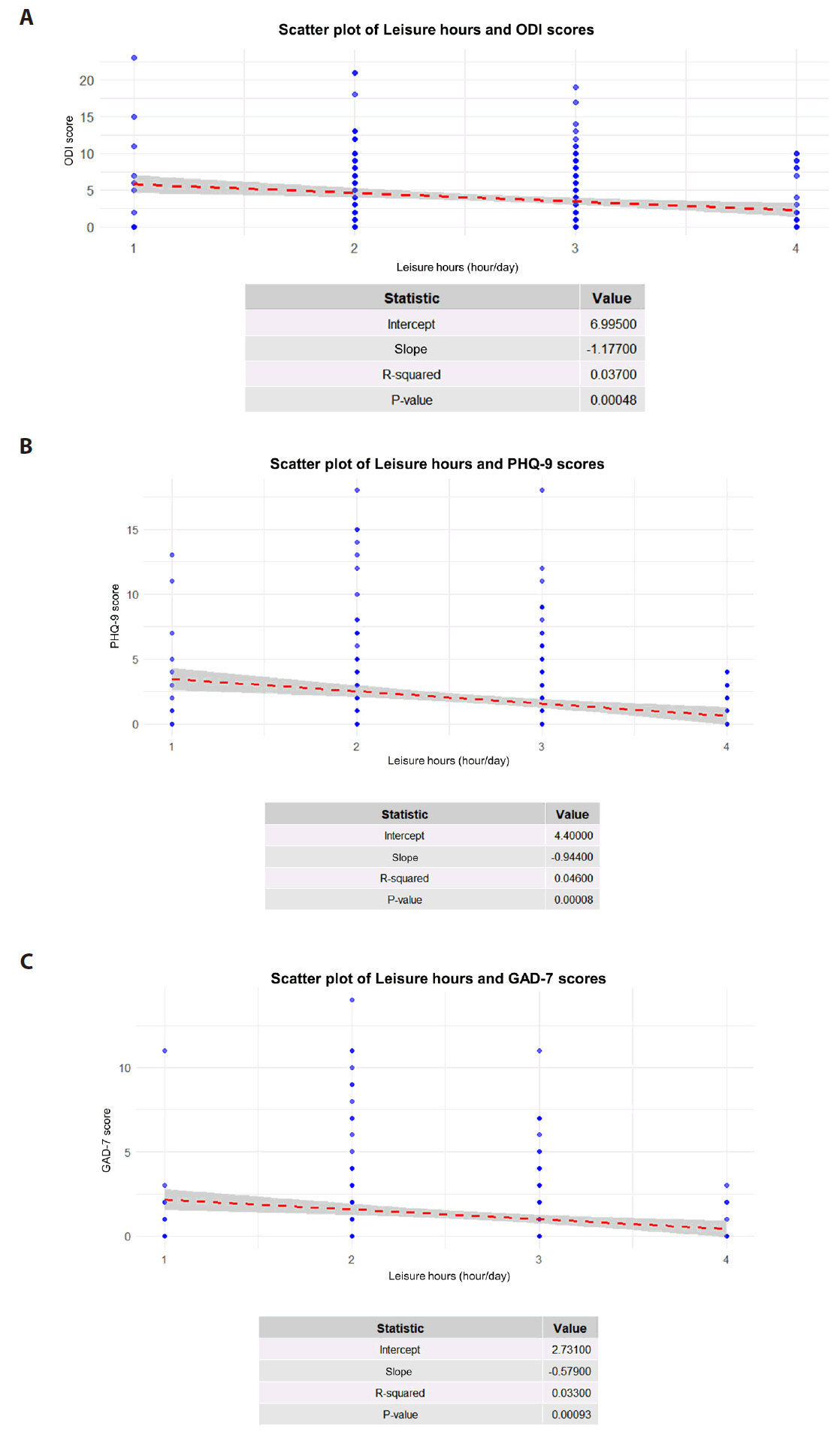

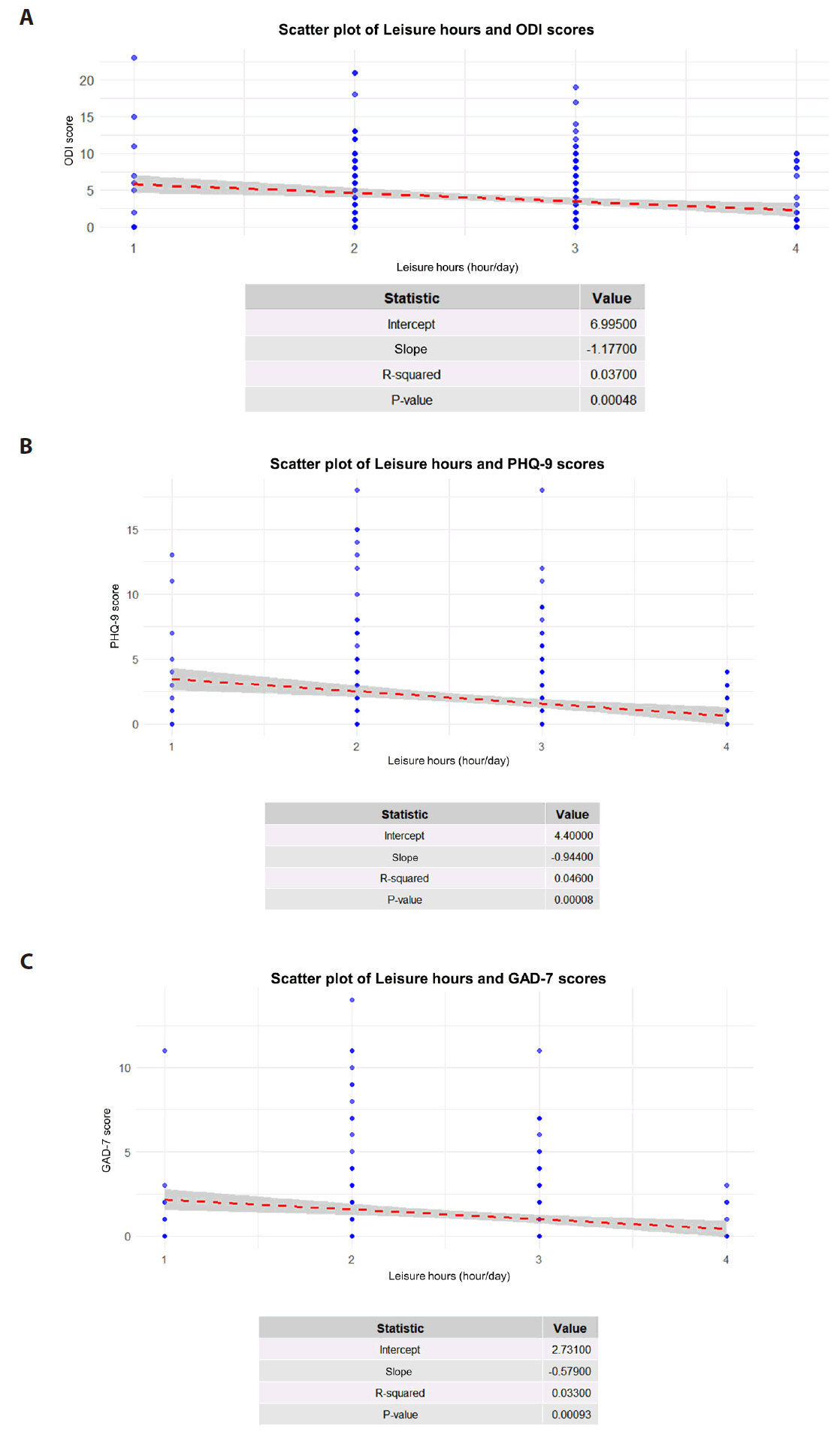

- The correlation analysis between the responses to the question "I am given sufficient breaks during work" (1: Strongly Disagree, 2: Disagree, 3: Agree, 4: Strongly Agree) and health scores showed a negative correlation across all measures: ODI (slope: –1.17, p < 0.001), PHQ (slope: –0.94, p < 0.001), and GAD (slope: –0.58, p < 0.001) (see Figure 9). This indicates that workers who receive sufficient breaks tend to have better physical and mental health.

- Statistical analyses of differences among work subcategories were conducted. For the results below, differences were considered statistically significant when p<0.05. The adjusted P-value, indicated in the tables below, refers to a P-value that has been modified to account for multiple comparisons.

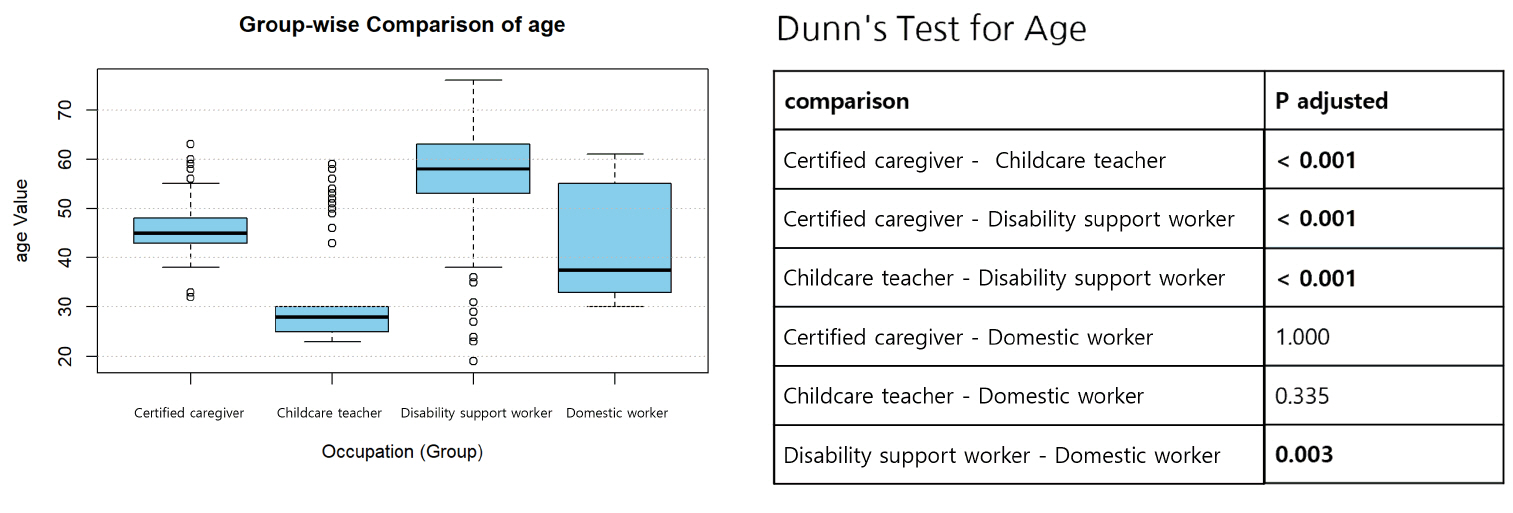

- As shown in Figure 10, analysis of age by job category was conducted based on responses to the survey item, "Please indicate your age", comparing different job categories. The Kruskal-Wallis test indicated statistically significant differences in age across the job categories, rejecting the null hypothesis.

- A follow-up Dunn’s test revealed that the age of disability support workers was statistically significantly higher than that of certified caregivers, childcare teachers, and domestic workers. Furthermore, certified caregivers were found to be significantly older than childcare teachers.

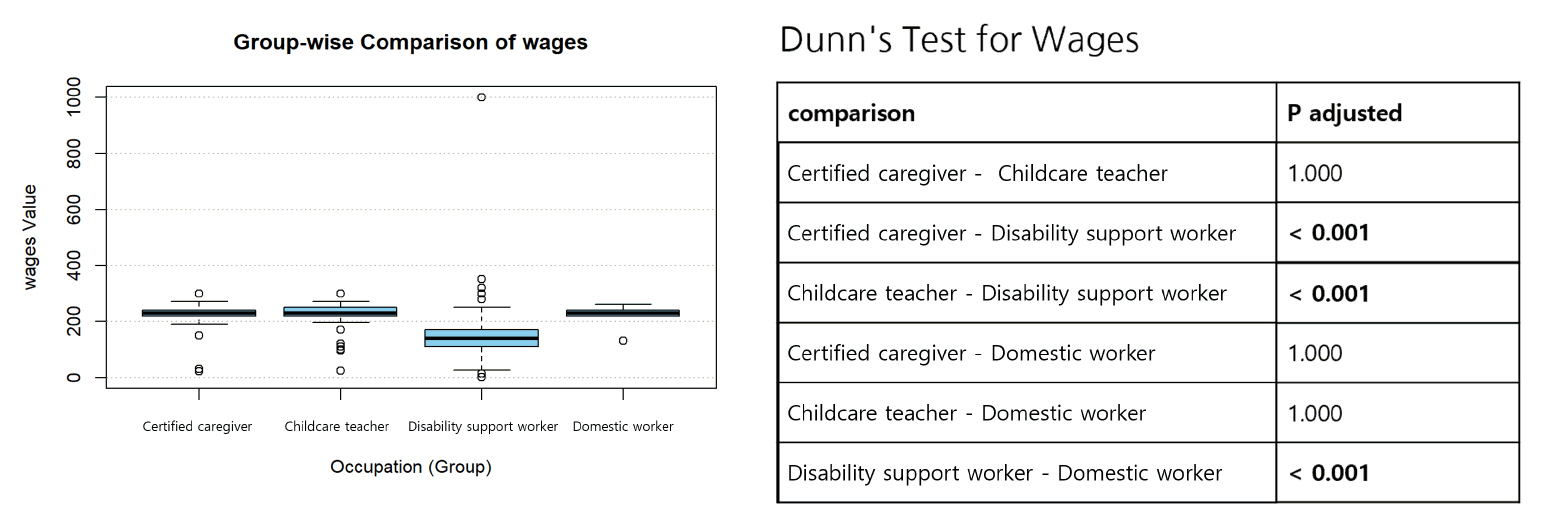

- Figure 11 shows analysis of wage by job category based of wage by job category was based on responses to the survey item "What was your average monthly income (after tax) over the past three months? (____ ten thousand KRW)", comparing different job categories. The Kruskal-Wallis test indicated statistically significant differences in wage across the job categories, rejecting the null hypothesis.

- A follow-up Dunn’s test revealed that the wages of disability support workers were statistically significantly lower than those of certified caregivers, childcare teachers, and domestic workers.

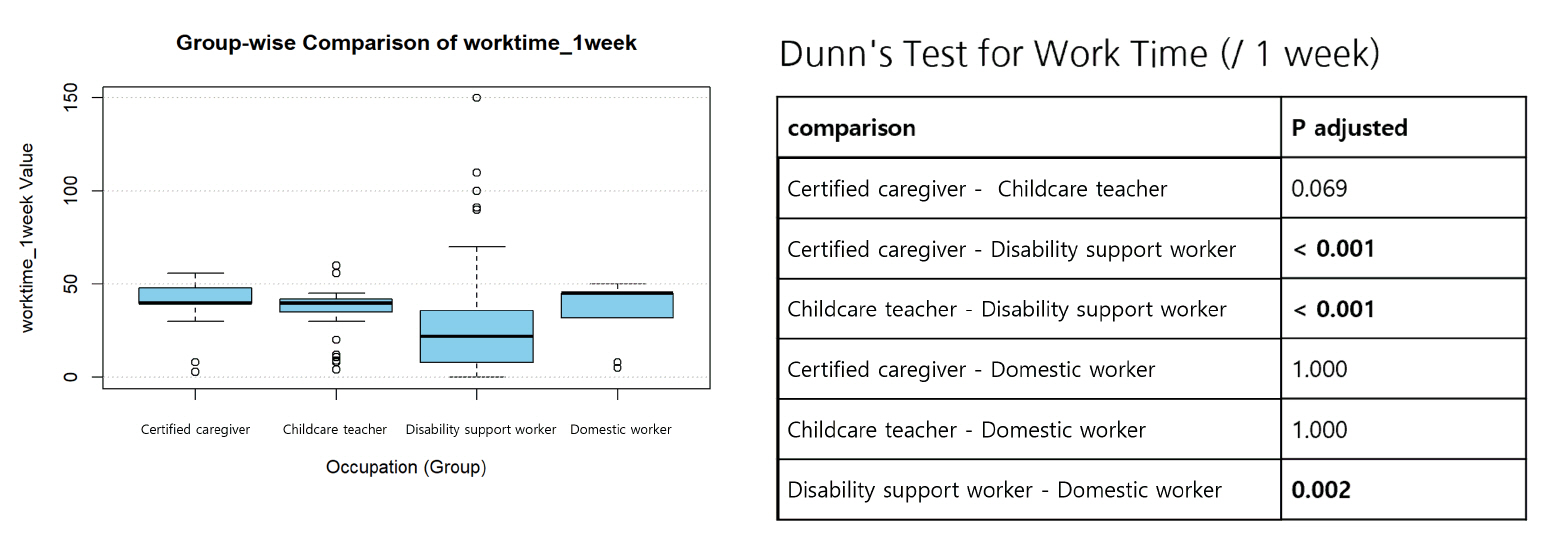

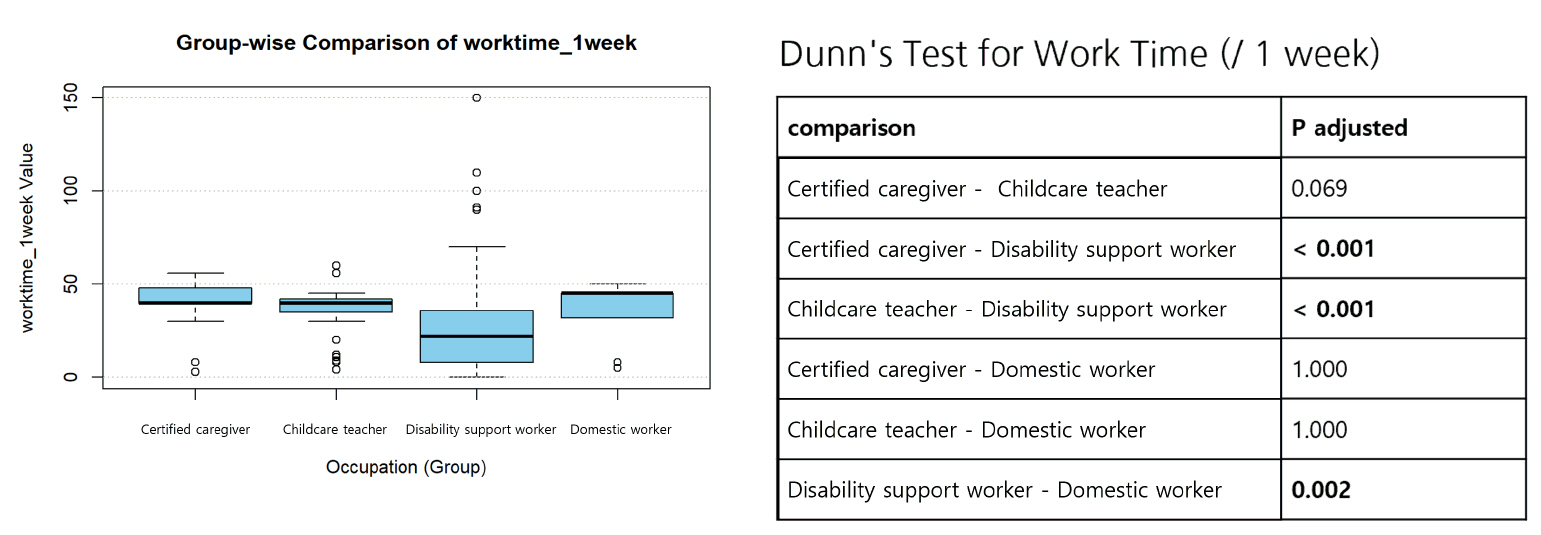

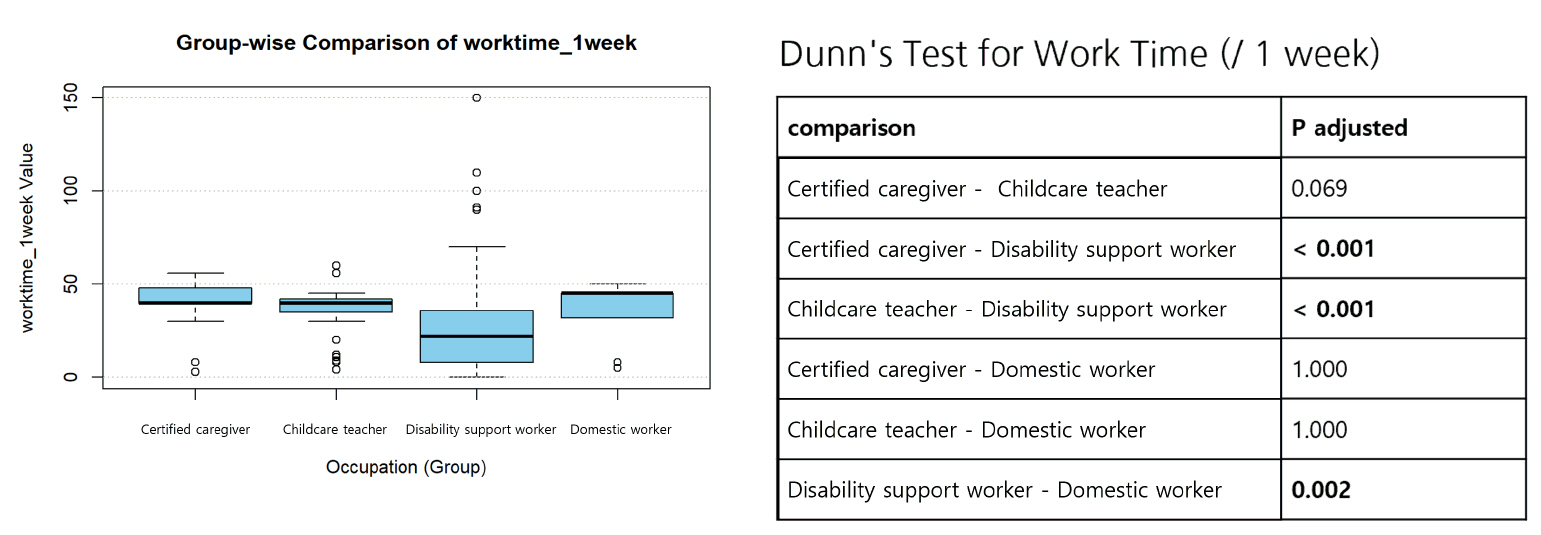

- Analysis of working hours by job category was based on responses to the survey item "Over the past month, how many hours per week, on average, did you engage in care work? (Total _ hours)", comparing different job categories as shown in Figure 12. The Kruskal-Wallis test indicated statistically significant differences in working hours across the job categories, rejecting the null hypothesis.

- A follow-up Dunn’s test revealed that the working hours of disability support workers were statistically significantly lower than those of Certified caregivers, childcare teachers, and domestic workers.

- Figure 13 presents the analysis of job satisfaction by job category conducted by aggregating responses to job satisfaction-related questions into a composite score and comparing the scores across different job categories.

- The Kruskal-Wallis test indicated statistically significant differences in job satisfaction across the job categories, rejecting the null hypothesis.

- A follow-up Dunn’s test revealed that the job satisfaction of domestic workers was statistically significantly lower than that of certified caregivers and disability support workers.

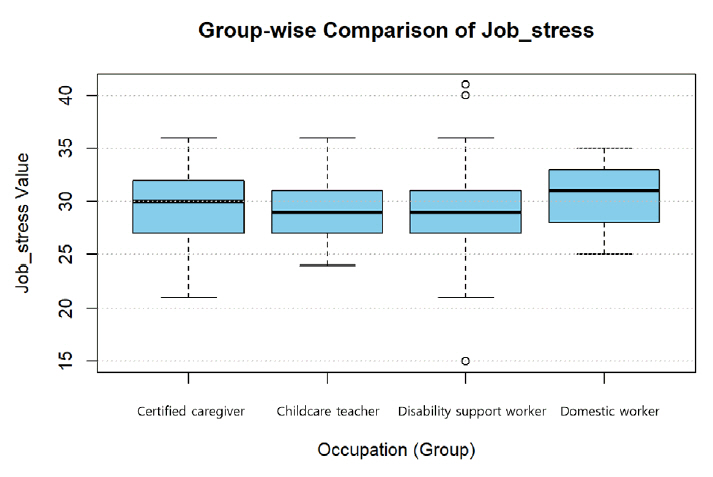

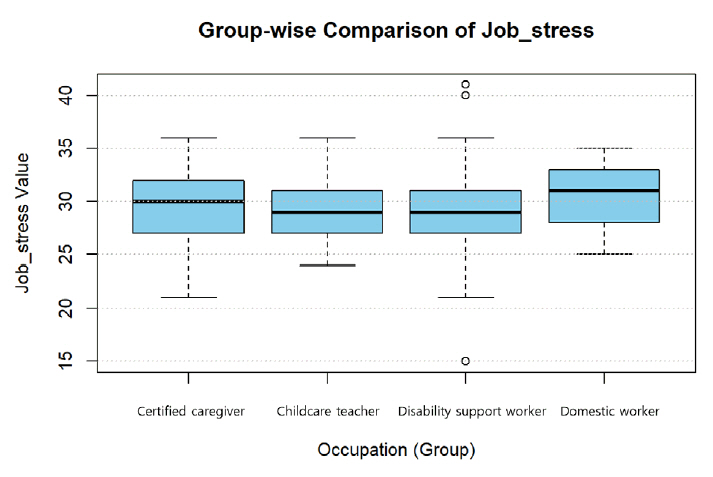

- Analysis of job stress by job category was conducted by aggregating responses to job stress-related questions into a composite score and comparing the scores across different job categories.

- The Kruskal-Wallis test found no statistically significant differences in job stress across the job categories, thus failing to reject the null hypothesis (see Figure 14).

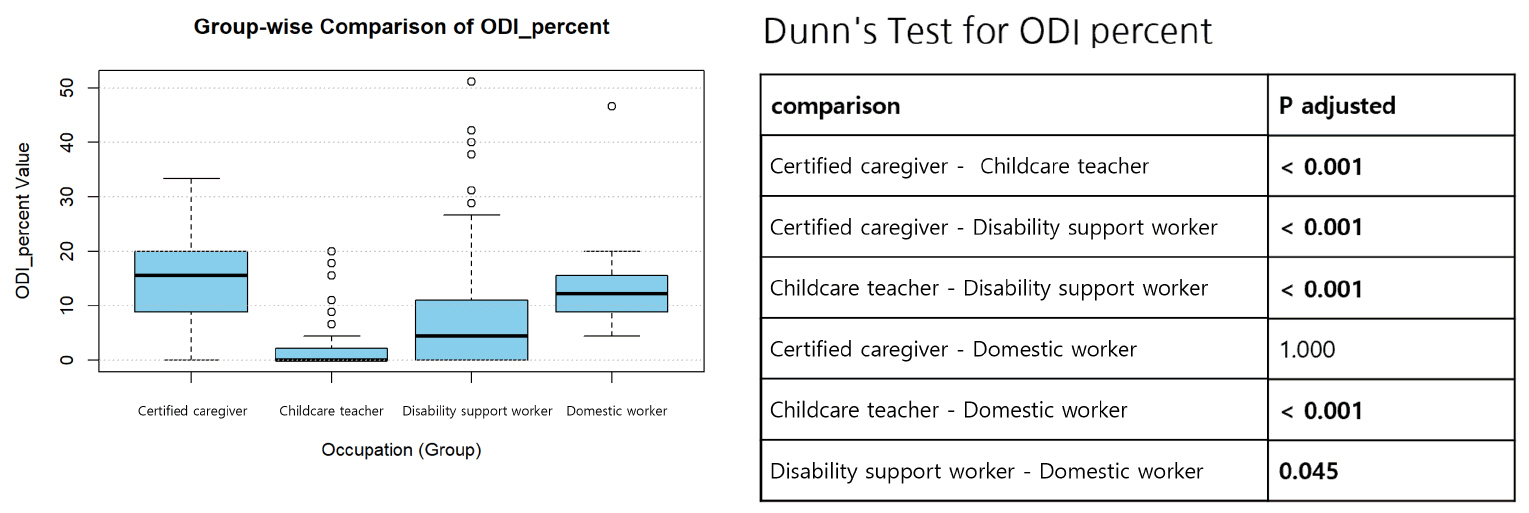

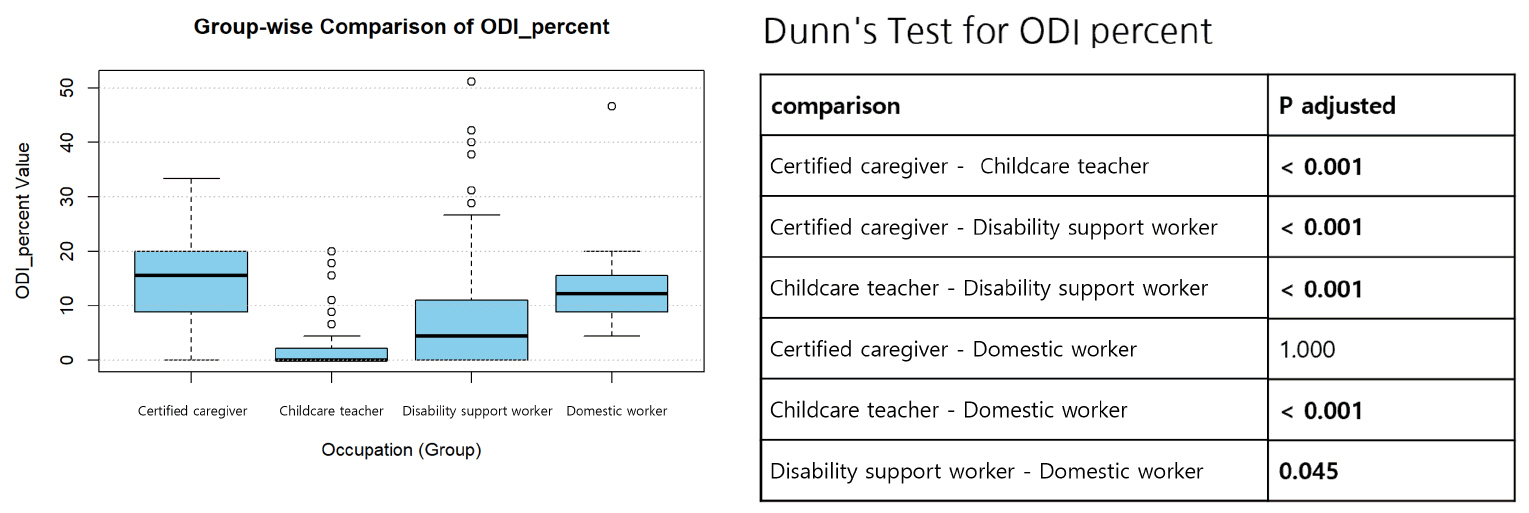

- Analysis of low back pain by job category was conducted by converting survey responses into Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) percent scores and comparing them across different job categories, as shown in Figure 15.

- The Kruskal-Wallis test indicated statistically significant differences in low back pain across the job categories, rejecting the null hypothesis. The median ODI percent scores, in descending order, were: certified caregivers, domestic workers, disability support workers, and childcare teachers.

- A follow-up Dunn’s test revealed that, except for the difference between certified caregivers and domestic workers, all other pairwise comparisons of low back pain showed statistically significant differences.

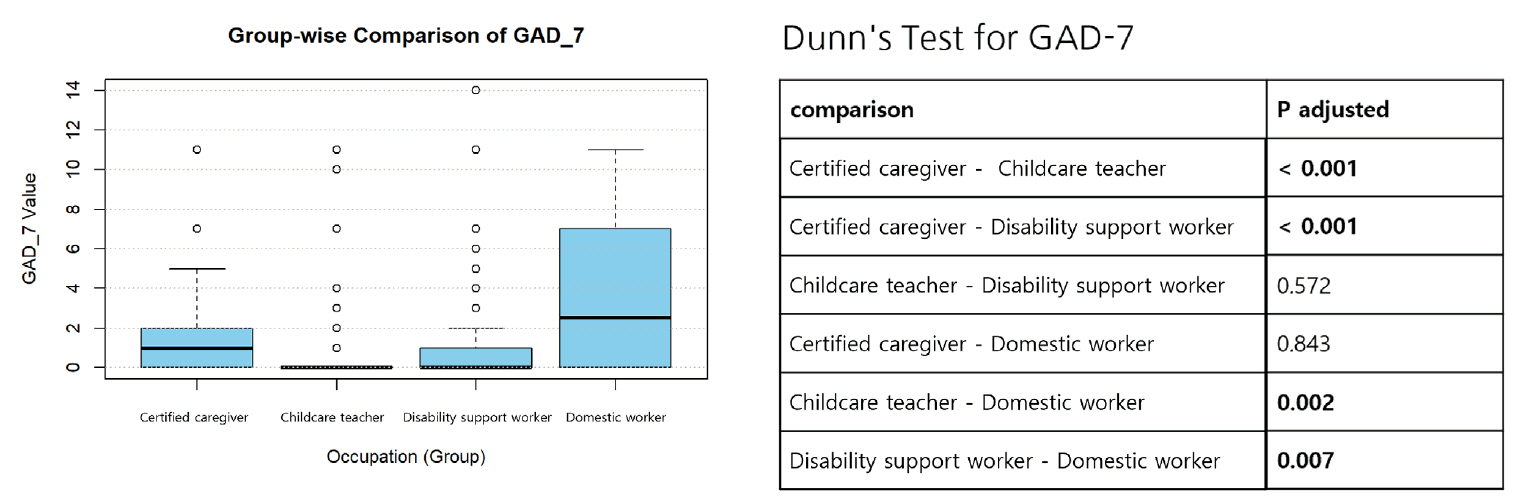

- Figure 16 illustrates the analysis of anxiety by job category conducted by converting survey responses into Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scores and comparing them across different job categories.

- The Kruskal-Wallis test indicated statistically significant differences in anxiety across the job categories, rejecting the null hypothesis.

- A follow-up Dunn’s test revealed that certified caregivers and domestic workers had statistically significantly higher GAD-7 scores compared to childcare teachers and disability support workers.

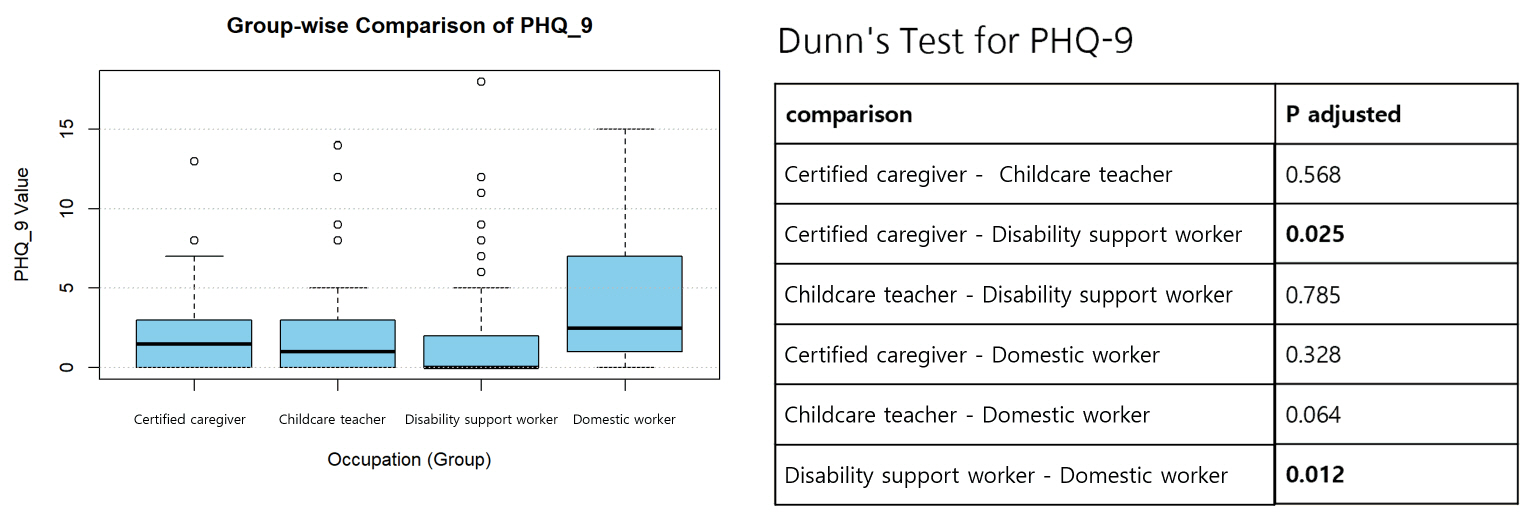

- Figure 17 presents the analysis of depression by job category conducted by converting survey responses into Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scores and comparing them across different job categories.

- The Kruskal-Wallis test indicated statistically significant differences in depression across the job categories, rejecting the null hypothesis.

- A follow-up Dunn’s test revealed that disability support workers had statistically significantly lower PHQ-9 scores than certified caregivers and domestic workers.

- Overall, wages and weekly working hours show a positive correlation, indicating that higher working hours are generally associated with higher wages. However, there are groups with low weekly working hours regardless of income level. While no distinct trends were observed between job categories, certified caregivers and childcare teachers tended to have relatively higher wages and weekly working hours compared to other occupations. (see Supplementary Figure S1)

- Examining the overall distribution, ODI percent scores do not show a strictly proportional relationship with age. However, the maximum ODI percent score tends to increase with age, while scores below the maximum are more evenly distributed. Additionally, the age distribution of childcare teachers is primarily concentrated in two groups: those under 30 and those over 45, whereas the age distribution of certified caregivers is more centered compared to disability support workers. (see Supplementary Figure S1)

- Weekly working hours were relatively high among certified caregivers and childcare teachers. However, the relationship between weekly working hours and health scores did not exhibit a clear trend. (see Supplementary Figure S2)

- Weekly working hours were relatively high among certified caregivers and childcare teachers. However, the relationship between weekly working hours and job satisfaction or job stress did not exhibit a clear trend (see Supplementary Figure S3)

- Qualitative Research

- The study involved a total of nine participants who were interviewed based on the questions outlined in Supplementary Table S1. Each interview lasted approximately 60 to 90 minutes. The interview period spanned from early to late October 2024. Each session was conducted by one or two researchers. To ensure the confidentiality of participants, they were assigned codes based on their professional fields in alphabetical order, rather than using their real names. The basic demographic information of the participants is presented in Table 1.

- Table 2 was compiled based on both the interview details and additional research. Notably, both household managers and domestic workers were found to participate in regular "monthly" training sessions. Since the format of basic education for household managers closely resembles that of domestic workers, it has been omitted from further discussion.

- The expressions related to the process and motivation for entering the profession can be broadly categorized into three main themes as shown in Table 3. The first theme that emerged from the interviews was that entry and re-entry into these professions were relatively easy. A domestic worker stated, "Even if I take a break, it's relatively easy to start again. There are many opportunities for reemployment through various associations." (Participant 1). Similarly, a childcare teacher mentioned, "It is easy to enter the field." (Participant 5).

- The second theme highlighted the role of referrals and networking. A disability support worker stated in the interview, "Through the process of assisting people with disabilities, relationships naturally form, and I receive new job opportunities through these connections." (Participant 9). Some participants independently found new care recipients through personal connections. However, others reported a high dependency on agencies, making it difficult to secure work autonomously.

- Lastly, participants frequently mentioned limited job options for their age group. Most interviewees were middle-aged, in their 50s or 60s, and noted that the range of available professions was narrow, leading them to choose from a restricted set of options.

- This study qualitatively analyzed the experiences of care workers by identifying key themes based on interview data. The findings were categorized into five main areas, each reflecting common themes from the participants' responses. The results, along with the frequency of responses, are presented in Tables 4.

- The perception of wage was divided into positive and negative experiences and classified into four subcategories: Low Salary Compared to Workload, Commission and Overtime Issues, Supplementing Family Income and Additional Income.

- In cases of dissatisfaction, participants generally felt underpaid for the work intensity, and overtime or commission issues contributed to psychological stress. In contrast, those who were satisfied found that the income helped with economic difficulties, and some also viewed it as supplemental income even if it wasn’t their main source of income.

- Coping strategies in unfair situations were classified into three subcategories: acceptance, emotional expression, and formal reporting.

- (ⅰ) Acceptance (No Other Choice): "There are no other options, so I just tolerate it. I’m afraid if I raise an issue, it will cause even bigger problems." (Participant 5)

- (ⅱ) Emotional Expression: "I just suppress my anger. I’m afraid if I speak out, I’ll face disadvantages." (Participant 7)

- (ⅲ) Formal Reporting: "Once I reported an issue to the district office, but it was so complicated that I won’t do it again." (Participant 4)

- Participants generally handled unfair situations personally or sought institutional help when needed. The majority of participants tolerated the situation and expressed emotional reactions internally. Only a few participants attempted to resolve issues through formal reporting.

- Internal perception refers to how participants themselves view the job, while external perception refers to how those around them perceive the participant’s job. Both internal and external perceptions were divided into positive and negative categories. Internal perceptions were classified into five categories, while external perceptions were divided into three subcategories as shown in Table 5.

- Regarding internal perception, participants experienced personal satisfaction and fulfillment, but also struggled with low social recognition. In terms of positive aspects, responses varied between enjoyment (3) and a sense of gratitude (3), while negative aspects such as burnout (2) and lowered self-esteem (3) also emerged. External perceptions were split between positive and negative feedback, with expressions of customer gratitude positively influencing job satisfaction. On the other hand, low social recognition and repetitive tasks often led to dissatisfaction.

- Factors influencing mental health and coping strategies were classified into three subcategories.

- • (i) Stress Factors

- Stress mainly stemmed from external factors like the work environment, relationships with customers, and work intensity.

- o "Working in a place with no air conditioning on hot summer days was really tough. I’d be sweating a lot and feel exhausted after work. I didn’t want to go home then." (Participant 5)

- o "Some customers wouldn’t use the cup we cleaned, instead asking for a tumbler. It often felt like we were shadow workers." (Participant 7)

- • (ii) Impact of Stress

- Psychological impacts included lowered self-esteem and feelings of depression.

- o "When we’re treated like this, I sometimes wonder if I’m doing something wrong. I often think, why do I have to do all this?" (Participant 3)

- Physical symptoms included headaches and fatigue.

- o "When I get home, I immediately look for medicine because of the headache. It’s not that the work is hard, but the tension makes me more tired." (Participant 6)

- • (iii) Coping Strategies

- o "During breaks, I eat snacks or do stretching exercises to relieve tension. Without that, I wouldn’t be able to continue for long." (Participant 4)

- Social coping involved conversations with colleagues.

- o "Talking with coworkers who are doing the same job really helps. We all empathize because we go through similar things." (Participant 2)

- Lastly, formal form of support was also utilized.

- "I got support through health checkups from Green Hospital. It would be great if there were more support like this." (Participant 8)

4. Results

1) Statistical Analysis of All Survey Participants (Careworkers)

(1) General characteristics

(2) Working Hours and Leisure Time

(3) Average Monthly Wage and Household Total Income

(4) Job-Related Scores

(5) Physical and Mental Health Scores

(6) Working Hours and ODI Percent

(7) Job Satisfaction and Physical and Mental Health Scores

(8) Leisure Time and Physical and Mental Health Scores

2) Statistical Analysis of Differences Among Care Work Subcategories

(1) Age Distribution by Job Category

(2) Wage Distribution by Job Category

(3) Working Hours Distribution by Job Category

(4) Job Satisfaction Distribution by Job Category

(5) Job Stress Distribution by Job Category

(6) Lower Back Pain Distribution by Job Category

(7) Anxiety Distribution by Job Category

(8) Depression Distribution by Job Category

(9) Relationship Between Wage and Working Hours by Job Category

(10) Relationship Between Age and ODI by Job Category

(11) Relationship Between Working Hours and Anxiety, Lower Back Pain and Depression by Job Category

(12) Relationship Between Weekly Working Hours, Job Satisfaction, and Job Stress by Job Category

1) General characteristics

2) Cross-Analysis Results

(1) Perception of wage

(2) Coping Strategies in Unfair Situations

(3) Internal and External Perception of the Job

(4) Mental Health Impact Factors and Coping Strategies

- These results provide a comprehensive picture of the challenges and experiences of care workers. The following discussion interprets these findings in light of current policy and practice, and suggests directions for future improvement.

- This quantitative study aimed to identify the correlations between various factors, such as wages, job satisfaction, job stress, and health scores of care workers through statistical analysis. Both online and offline surveys were conducted, and all respondents who completed the survey were included as research participants. The key findings of this study are as follows.

- This study identified correlations between health scores and other factors among care workers. Among chronic diseases, hypertension was found to have the highest prevalence. The health scores examined in this study (ODI percent (lower back pain), PHQ-9 (depression), and GAD-7 (anxiety)) all indicate better physical or mental health when the scores are lower. The ODI percent score showed an inverse relationship with working hours, suggesting that an increase in working hours has a visible impact on the deterioration of physical health conditions such as lower back pain. Additionally, higher job satisfaction was associated with lower ODI percent, PHQ, and GAD scores, indicating that maintaining physical and mental health during care work is linked to higher job satisfaction.

- This study also identified differences among subcategories of care work. For example, as previously mentioned, the average age of disability support workers was statistically significantly higher than that of certified caregivers, childcare teachers, and domestic workers. Furthermore, the wages of disability support workers were statistically significantly lower than those of certified caregivers, childcare teachers, and domestic workers. The working hours of disability support workers were also statistically significantly lower than those of certified caregivers, childcare teachers, and domestic workers, while their PHQ-9 (depression) scores were statistically significantly lower than those of both certified caregivers and domestic workers.

- The results above suggest that establishing an environment that supports the physical and mental well-being of care workers may have a positive long-term impact on the care labor sector. They also suggest that the higher average age of disability support workers may lead to fewer working hours, which in turn results in lower wages but has a positive impact on depression scores.

- However, as other factors may influence age, wages, working hours, and depression scores, further research is warranted. In particular, unknown social factors may contribute to the relatively high average age of disability support workers. Moreover, being designed as a cross-sectional study, this study analyzes correlations rather than causal relationships and it is not possible to draw definitive conclusions regarding causality.

- Although quantitative research on wages, health scores, and working hours of care workers in South Korea has been increasing recently, studies that specifically analyze the correlations between these variables remain limited. Serving as a starting point for further statistical analyses, this study may help identify the key factors necessary for improving the working environment of care workers.

- This study sheds light on the structural problems faced by care workers, which are linked to their health and social perceptions. It is expected to contribute to redefining the value of care work and improving policies related to workers' health and welfare. The study also aims to share the findings with welfare organizations such as "푸른초장 (NGO that assists care workers)”, hoping to positively influence the situation. The insights gathered from the study will also help inform future educational programs for care workers, focusing on improving their physical and mental health.

- The study's findings provide a foundation for various activities moving forward. Educational materials can be developed and distributed to care workers, providing them with accurate information about their current situation and guiding them toward understanding their future direction. The study revealed cases where resolving unfair situations was challenging, so the educational materials will include information on legal reporting procedures and rights. Additionally, the materials will provide guidance on preventing musculoskeletal disorders, such as joint protection and exercises to reduce strain.

- During the research process, one major challenge faced was the lack of available quantitative data on care workers' health, which was necessary for the study. Initially, the plan was to use existing data, but due to insufficient numerical data, the research approach was adjusted. A new survey was designed and distributed to gather the necessary data, which allowed for the successful completion of the quantitative part of the research. However, the study could only identify correlations rather than causal relationships. To address this limitation, further interviews with the survey participants will be conducted to explore the detailed causes behind the relationships identified in this study. In addition, conducting a cohort study rather than a cross-sectional study, as a follow-up study, would enable the investigation of causal relationships.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Table S1.

Supplementary Figure S1.

Supplementary Figure S2.

Supplementary Figure S3.

Figure 2.Other Response Distribution - (A) Primary Income Earner (B) Salary Satisfaction (C) Highest Level of Education (D) Chronic Disease.

Figure 8.Relationship between Job Satisfaction Scores and Health Scores: Scatter Plot and Boxplot (A) ODI Scores, (B) PHQ-9 Scores, (C) GAD-7 Scores.

Figure 9.Scatter Plot of Leisure Time and Health Scores: (A) ODI Scores, (B) PHQ Scores, (C) GAD Scores.

Figure 12.Boxplot of Working Hours Distribution by Job Category and Post-hoc Analysis Using Dunn’s Test.

Figure 13.Boxplot of Job Satisfaction Distribution by Job Category and Post-hoc Analysis Using Dunn’s Test.

Figure 15.Boxplot of Lower Back Pain Distribution by Job Category and Post-hoc Analysis Using Dunn’s Test.

Figure 17.Boxplot of Depression Distribution by Job Category and Post-hoc Analysis Using Dunn’s Test.

Table 1.Basic Information of Research Participants

Table 2.Summary of the Hiring Process by Occupation

Table 3.Common Themes Related to the Occupational Entry Process

Table 4.Perceptions of salary with illustrative interview quotations

Table 5.Internal and External perception of the job with illustrative interview quotations

- An, H. L. (2023). Long-term care facility caregivers’ need to reduce physical burdens. Korean J Occup Health Nurs, 32(4), 141-151. https://doi.org/10.5807/kjohn.2023.32.4.141

- Griggs, D. J., Nilsson, M., Stevance, A., & McCollum, D. (2017). A guide to SDG interactions: From science to implementation. International Council for Science. https://doi.org/10.24948/2017.01Article

- Hwang, J. H., & Han, H. S. (2024). A study on the relationship between job stress and job satisfaction of activity assistant for the disabled: The dual mediating effects of psychological well-being and resilience. Journal of Emotional & Behavioral Disorders, 40(2), 133-157. https://doi.org/10.33770/JEBD.40.2.7Article

- Hwang, J. W., & Jeong, S. C. (2023). A study on the improvement of caregiver's working environment and health relationship: Based on the development of a social cooperative caregiver platform. Asia-Pacific Journal of Convergent Research Interchange, 9(4), 137-148. http://dx.doi.org/10.47116/apjcri.2023.04.12Article

- Kim, J. Y. (2022). A Study About the Constructuring and Negotiation of Working Hours of Personal Assistants for People with Disabilities. The Journal of Humanities and Social science (HSS21), 13(5), 3925-3940. http://dx.doi.org/10.22143/HSS21.13.5.272Article

- Koo, E. M., & Park, S. H. (2013). The influence of teachers' health and organizational health on child care teachers' turn-over intentions. Journal of Early Childhood Education & Education Welfare, 17(4), 33-53. https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/landing/article.kci?arti_id=ART001830685

- Lee, H. M., & Kim, T. H. (2023). Comparison of musculoskeletal symptoms and quality of life in personal assistants for individuals with brain lesions and autism - Focusing on visitors to occupational therapy rooms in Changwon District. Korean Society of Community-Based Occupational Therapy, 13(3), 10-20. https://doi.org/10.18598/kcbot.2023.13.3.02Article

- Lee, S. J. (2012). Simcheung bunseok 1 nodong-euroseo-ui dolbom [In-depth analysis: Care work as market labor]. People Power 21. https://www.peoplepower21.org/welfarenow/%EC%9B%94%EA%B0%84%EB%B3%B5%EC%A7%80%EB%8F%99%ED%96%A52012/873577

- Lee, S. Y., Hwang, J. W., & Lee, S. G. (2024). Issues and challenges to guarantee domestic workers' right to health and rest — The current status of domestic workers and policy responses in Seoul. Journal of Social Law Studies, 52, 239-271. https://doi.org/10.22949/kassl.2024..52.007Article

- Lee, Y. R., Park, S. N., & Chu, M. S. (2014). Impact of perceived health status, depression and job stress on job satisfaction among child care providers. Korean Academic Society of Home Health Care Nursing, 21(1), 26-35. https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/landing/article.kci?arti_id=ART001885053

- Park, C. I., Lee, S. R., Yoon, J. Y., & Shin, H. G. (2013). The status of industrial accidents and protective measures for care service workers [Research report]. Korea Labor Institute. https://www.kli.re.kr/kli/rschRptpView.es?mid=a10102040000&sch_rsch_fld_no=4&pblct_sn=7358

- Statistics Korea. (2025). Population projections: Key demographic indicators (sex ratio, population growth rate, population struc-ture, dependency ratio, etc.) [Data set]. Statistics Korea. https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1BPA002&conn_path=I2

- Yoon, J.Y. (2013). Legislative directions for protecting care workers. Korea Public Interest Law Foundation. https://www.kpil.org/data/bbs/actionData/137-1

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

IGEE

IGEE

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite